In 1959 two men trailered a horse to a dealer's yard in East-Westfalia, where they intended to exchange it for another, which would be more suitable for dressage. It was nothing uncommon in those days to do such exchange deals

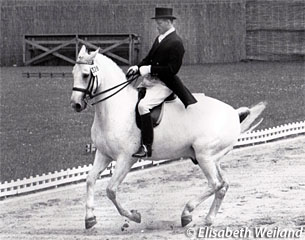

and the duo was offered a small 4-year old gelding The two were Harry Boldt, then a young talented German dressage rider, and Gustav Pütter, owner of a stud farm for which Boldt broke and trained horses. The exchange object was a grey Westfalian, not very impressive looking, barely 160 cm tall and with a rather short back. Fortunately this one had more quality and even though he was too small for Boldt, Gustav Pütter agreed to trade him for his original horse.

As atypical as it sounds this was the first meeting of horse and rider who would go on to become one of Germany’s most consistent and most successful dressage pairs. Neither Boldt nor Pütter expected it themselves back then. Boldt, in his early 20s, had already been successful with the chestnut Holsteiner gelding Brokat. The horse had carried him from A-leve to Grand Prix dressage and was trained by his famed father Heinrich, a Hamburg born renowned riding instructor based in Essen.

Boldt never expected that the plain looking Westfalian named Remus would become Harry's claim to fame. “Remus was four and just broken in when we took him," Boldt told Eurodressage. "He looked rather a bigger pony than a horse at that time and was too small for me. Though he had three very good gaits I never seriously thought he would become an Olympic horse one day.”

It wasn’t Remus’ height nor appearance which hindered him from becoming an international horse, but his conformation. His croup was a bit higher than his withers and the back quite short. These compact features were the heritage of his famous father, the Polish bred Anglo Arab Ramzes x who had been covering at the famous Vornholz Stud owned by Clemens von Nagel, breeder of international Grand Prix horses Pernod, Chronist, Afrika, Adular and Macbeth.

Ramzes had been an impressive grey clearly stamped by the pure Arab. He has sired exceptional jumping horses such as Hans-Günter Winkler’s grey Holsteiner Romanus, Fritz Ligges’ Olympic champion Robin as well as several exceptional dressage horses. Ramzes passed some disadvantages of his Arabian genes on to Remus, but he also gave him the unique Arabian flair, though maybe a bit less than his other great dressage son, Josef Neckermann’s Mariano. Due to his very classical training Remus overcame his genetic challenges and transformed into an international calibre horse.

The Early Days

Harry Boldt soon realised that the small grey gelding, which fortunately grew another 6 more centimetres, had also inherited his father’s great intelligence and sensitivity which helped in the daily training. However, those who suppose Remus was the keen forward-mover many Arabs are are proved wrong. ”As a young horse Remus was rather lazy in the way that he didn’t want to go forwards enough. It happened more than once that in the midst of his training he would halt and refuse to do one more step,” Boldt remembered the beginnings.

Harry Boldt soon realised that the small grey gelding, which fortunately grew another 6 more centimetres, had also inherited his father’s great intelligence and sensitivity which helped in the daily training. However, those who suppose Remus was the keen forward-mover many Arabs are are proved wrong. ”As a young horse Remus was rather lazy in the way that he didn’t want to go forwards enough. It happened more than once that in the midst of his training he would halt and refuse to do one more step,” Boldt remembered the beginnings.

Those training sessions had to be held outside the whole year because there was just no indoor arena available. No matter if there was a storm, rain or snow, Remus was worked outside and even though it wasn’t very comfortable for his rider it did the horse good. “We hadn’t an indoor arena when I began to work with Remus he was quickly used to any kind of weather. This was sometimes an advantage later on when we competed," Boldt explained.

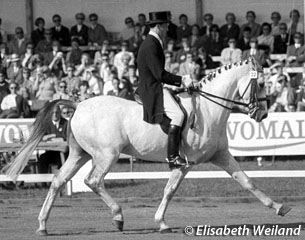

Remus' decent and reliable character proved valuable in later years. Remus never got nervous or tense, he was always quiet with a well-balanced temperament so his rider admitted that “Remus could have had more temperament, a bit more pep.” Training the horse up the levels and teaching him the movements wasn’t the greatest problem; it was overcoming his disadvantages in his conformation. “At the beginning I had quite some difficulties with Remus’ throughness and to ride him over the back properly. Moreover he tended to pace in his walk.”

The Westfalian’s short topline didn’t help either because he gave the impression of being a bit tight in his neck, which prompted some judges to say the horse had to stretch his neck more. The Swiss Marianne Gossweiler, who would later compete against Boldt and Remus in the Olympic Games, confirmed this: “Sometimes Remus became a bit tight in the neck, but this was a result of his conformation. He was never pulled together and reacted to very fine aids.”

Another problem occurred: Remus liked to pull his tongue high or put it out of his mouth. During the years to come Boldt was successful in handling it, but he honestly admitted that “I never completely solved it.”

Master Mind Remus

Boldt overcoming Remus’ physical disadvantages so successfully that he trained the horse to S-level within a reasonable times not only had its reasons in Remus’ great intelligence and will to learn, but also in the fact that his rider strictly followed the classical principles of dressage.

Boldt overcoming Remus’ physical disadvantages so successfully that he trained the horse to S-level within a reasonable times not only had its reasons in Remus’ great intelligence and will to learn, but also in the fact that his rider strictly followed the classical principles of dressage.

In 1962 the pair first came into the spotlight on the German dressage scene. Remus impressed with his relaxation and extraordinary elasticity Though the pair showed promise on a scene which was smaller than nowadays Remus had his real breakthrough a year later. In 1963 he made his debut at Grand Prix level and started at Aachen where he placed 3rd behind Dr. Josef Neckermann's Hanoverians, Förster and Asbach, but ahead of Liselott Linsenhoff’s talented thoroughbred Monarchist xx.

This results entailed a qualification for the unofficial European Championships in Copenhagen the same year. Remus had already placed a remarkable third in the Hamburg Dressage Derby in the spring. Unfortunately no German team could be sent because Neckermann’s hopeful Förster got a cold and had to be withdrawn. So Boldt and Dr. Reiner Klimke went as individuals and Remus impressed at his first start for Germany, winning the Intermediate and the individual silver medal behind the Swiss Henri Chammartin on the beautiful Swedish warmblood Wolfdietrich.

Remus’ good results and international acceptance were encouraging for the Olympic season to come. Though many might think so, it wasn’t the first time Harry Boldt tried to get an Olympic spot on the German team. Already 8 years earlier he had competed his father’s Brokat in the qualifications for Stockholm 1956 and now his Olympic dream was about to come true.

With Remus in hand and 8 years of added experience Tokyo was a realistic goal. The dream came even closer when the grey placed third in the Aachen Grand Prix behind Neckermann’s new star, Antoinette and Dr. Reiner Klimke’s huge Duellant-offspring Dux. These three were nominated on the team for the Olympic Games in Japan.

As Germany was by far the dominating dressage nation back then an Olympic gold medal was within reach and the chance for a medal could only be endangered by something unexistent nowadays: The team competition only took place if at least six nations would participate. Only weeks before the Games this number still wasn’t secured, but fortunately Japan and Sweden were able to send teams, the latter thanks to Neckermann’s generous offer to pay their travelling expanses which were enormous in the 1960s.

Harry Boldt and Remus met their team mates in September in Warendorf for a final team training under the guidance of general Horst Niemack. There the horses not only practised the exercises, but also “competed” against each other in an internal Grand Prix as well as a ride-off (nowadays the Grand Prix Special). Both times Remus placed third, one time behind Dux and another behind Antoinette. It wasn’t a surprising result as both horses had been superior to Remus during the season and especially Neckermann’s most beautiful Holsteiner mare Antoinette was considered to be Germany’s weapon for the individual medals.

Journey to Tokyo

On 28 September 1964 the German dressage and jumping horses and the Swedish dressage horses met in Holland to be loaded on a special KLM-plane which brought them to Japan. For all horses it was their first flight and the riders were understandably a bit concerned. The less concerned must have been Harry Boldt, because “we never had any problems with the transport. Remus was such a calm type of horse he was always placed next to nervous companions, of course also on the flight to Japan.”

On 28 September 1964 the German dressage and jumping horses and the Swedish dressage horses met in Holland to be loaded on a special KLM-plane which brought them to Japan. For all horses it was their first flight and the riders were understandably a bit concerned. The less concerned must have been Harry Boldt, because “we never had any problems with the transport. Remus was such a calm type of horse he was always placed next to nervous companions, of course also on the flight to Japan.”

Due to the resistant Swedish dressage horses which refused repeatedly to enter the gaitway onto the plane the flight had to be delayed for hours, but finally the journey to Asia could begin. With a stop in Anchorage to refuel the plane the valuable fright landed on Japanese soil unharmed and the horses were transported to the big racetrack more than 100 km away from Tokyo.

About 30 hours had been gone by since the departure, but luckily Remus was in very good shape and could start his training soon after.

It was hard to pinpoint a clear favourite. Sergej Filatow’s 1960 Olympic Champion Absent participated again, but the poor Russian horses had a strenuous journey by boat behind them which raised questions ob their level of fitness. Henri Chammartin’s European Champion Wolfdietrich wasn’t fit for sure and nobody knew if he could compete.

Only one thing seemed to be sure: “Remus hadn’t been considered to be a horse for the individual medals, absolutely not. In our team Neckermann and Antoinette had been the undoubted favourites and the chef d’equipe completely concentrated on them.”

The horses had almost one month to acclimatise after their arrival and were worked for an hour every day. They additionally got long hacks in walk or were led in hand to keep them busy. Two days before the Grand Prix there was the last intensive training session. For the first time at the Olympic Games the Grand Prix only counted for the team medals and served as a qualification for a kind of “ride-off”. Those results were added to the ones of the Grand Prix.

Boldt stressed that he was helped in his preparations, especially for the Grand Prix, by the late Olympic Champion Liselott Linsenhoff who had flown over to watch the dressage competitions.

Olympic Gold for Boldt and Remus

On 22 October Remus was the first of the German team horses to present himself to the judges Gustav Nyblaeus from Sweden, the Czech Frantisek Jandl and Colonel George Margot from France.

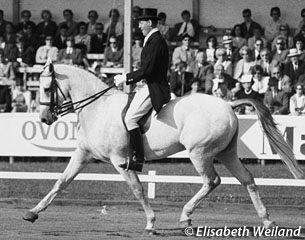

All the years of patient training now paid off, exactly in the minutes when it counted the most. Remus showed the best Grand Prix of his career so far, he excelled especially in the trot tour, showed an improved piaffe and passage and convinced with his extraordinary suppleness and elasticity. His total of 889 points meant the first place so far and it was obvious that this grey Westfalian was the one to beat on that day in 1964.

Favourites come and go. Absent, Chammartin’s reserve horse Woermann, Dux and Antoinette, who had to bad fortune to compete in a thunderstorm, could match Remus’ wonderful ride.

Rather unexpectedly Harry Boldt, only 34, and his 9-year old gelding had led the German team to its expected team gold medal and moreover had another gold in reach.

Remus was almost 20 points in lead and as he was so reliable it wasn’t unrealistic that he would maintain this position in the ride-off. As a matter of fact he showed a good performance once again, though lacking the brilliance of the prior day. Contrarily to the logistics of the Grand Prix, the riders now had to wait for hours for the results because the three judges watched all the rides once more on film before publishing their finals results.

The outcome was something unique in Olympic dressage: By only one point Remus lost the gold medal to Woermann, Chammartin's Swedish gelding. Many a time journalists have tried to compare this lead with very close results in other sports. One said Boldt and Remus had lost gold like a marathon runner who lost it by a fraction of a second after almost 42 km of running. This description may fit best.

On the one hand the result was a sensation, because nobody had expected Remus to do so well in his first Olympic Games, on the other hand it was disappointing to be so close to the highest honour possible in this sport and still not got it.

When asked 46 years later, Harry Boldt told Eurodressage: “I was really delighted having won the silver medal, but then I was annoyed because of the close result. I should have been only 2 points better for gold, but Chammartin was an experienced routinier.”

Boldt and his horse got a warm welcome back from thousands in Boldt’s hometown Iserlohn, even though after Tokyo his name and that of Remus were well known outside this Westfalian town.

More Silver Glory and Honour

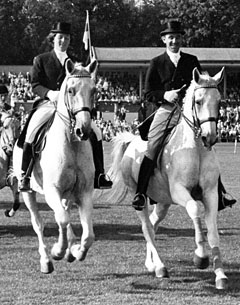

In 1965 the European Championships in Copenhagen, again set at the beautiful Bernstorff Park with its classicist castle, was the main goal of the season. In the spring of '65 Remus got an honour of a special kind: The German government itself asked if the riders of the winning Tokyo- team would give a display during the visit of Queen Elizabeth II to Germany. Remus along with Reiner Klimke's Arcadius and Dr. Josef Neckermann's Asbach were transported to Munich where they gave a remarkable display of horsemanship in the picturesque park of the Nymphenburg castle.

In 1965 the European Championships in Copenhagen, again set at the beautiful Bernstorff Park with its classicist castle, was the main goal of the season. In the spring of '65 Remus got an honour of a special kind: The German government itself asked if the riders of the winning Tokyo- team would give a display during the visit of Queen Elizabeth II to Germany. Remus along with Reiner Klimke's Arcadius and Dr. Josef Neckermann's Asbach were transported to Munich where they gave a remarkable display of horsemanship in the picturesque park of the Nymphenburg castle.

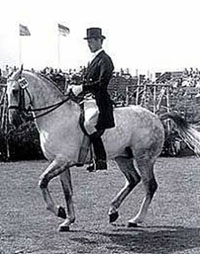

Of course Remus was nominated for the European Championships in Denmark and was naturally counted as one of the favourites. In Copenhagen 16 riders from 7 nations rode for the medals. The German duo confirmed their top position by winning the Grand Prix and helped the German team win its first of almost countless European Championship team titles.

In the ride-off the next day Remus was in top form again until bad luck took its toll. In the flying changes Harry Boldt’s spur got stuck in the saddle girth (the typical girth at the time with many cotton-wool strings). Remus jumped to the side and the flying changes couldn’t be shown properly which cost him the title. Yet again the individual silver behind the fit and fearless Wolfdietrich.

In 1966 the successful team of Tokyo remained unchanged after a stormy and rainy Aachen as qualifier for the first official World Championships to be held on the grounds of the Swiss cavalry in Berne. Remus had been second behind Dr. Klimke on his ever improving Hanoverian Dux, but ahead of Dr. Neckermann. The latter provided the location for the final team training before the horses travelled to Switzerland by the end of August. In Berne there were also S-level classes offered and Boldt and Klimke used these to participate in an Inter I- team competition along with Kurt Capellmann, father of Nadine and Gina. They took a good start by winning.

Remus performed very well in the Grand Prix to finish 3rd and the Germans won the team title. The chances for finally winning an individual title in the ride-off on 28 August were not so bad because Wolfdietrich’s brilliance was a little bit gone at age 15 and Remus was still at the top of the game with the Russians not yet able to fight for individual glory. So Remus' main rivals came from his own team: Dr. Reiner Klimke’s enormously trotting Dux and Remus’ half- brother, Dr. Neckermann’s beautiful Ramzes-son Mariano who had been trained by Boldt for a while before being bought by the famous German businessman in 1964.

Remus didn’t have Dux’ giant frame nor Mariano’s beauty, but he had one big advantage: he was absolutely reliable, not environment orientated at all and always able to perform faultfree. Harry Boldt presented the 11-year old with lots of elasticity and impulsion, especially in the trot tour and they managed to beat Dux, but when Mariano had finished his ride it was clear that Remus had once again won individual silver. It was nonetheless a very good result and the consistency of this faithful horse was outstanding, but Remus seemed to remain the bridesmaid forever.

Although he took revenge and won the German Championships some weeks later, leaving Mariano and Dux behind, Remus never won an individual title neither did his rider, not even with the powerful Hanoverian Woyzeck later on.

The Sad Downfall of Remus

After his individual bronze medal at his 3rd European Championships in 1967 Remus unfortunately lost his team place for the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico-City to the young talented Swedish stallion Piaff owned and ridden by Liselott Linsenhoff. Boldt and his long-time partner only flew as reserve pair. Boldt described his missing nomination as “one of his greatest disappointments in my career with Remus, together with Dr. Reiner Klimke competing him a year later, although Remus wasn’t at his peak anymore.”

After his individual bronze medal at his 3rd European Championships in 1967 Remus unfortunately lost his team place for the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico-City to the young talented Swedish stallion Piaff owned and ridden by Liselott Linsenhoff. Boldt and his long-time partner only flew as reserve pair. Boldt described his missing nomination as “one of his greatest disappointments in my career with Remus, together with Dr. Reiner Klimke competing him a year later, although Remus wasn’t at his peak anymore.”

A partnership which had lasted for a decade came to a rather sad end in 1969.

”In 1969 I left the Pütter Stud because I no longer wanted to compete Remus because of his leg troubles and because I didn’t see a future as a dressage rider there. The Pütter family didn’t want to realise Remus’ problems and gave him Dr. Reiner Klimke to compete," Boldt reported.

Klimke himself had to struggle with Dux being retired and Mehmed not yet ready for the big tour and therefore rode the ageing Remus at some shows in 1969, which the horse’s trainer and former rider regretted.

”Remus was finally retired at the indoor show in Dortmund in 1970. He then spent his last years at the stud of Pütters,” said Boldt.

Remus was able to enjoy his retirement for five years before he was put down in 1975 at age 20.

Harry Boldt will always remember him as the first horse he had trained from novice to Grand Prix. Thanks to Remus’ intelligence it only took him four years.

There is a German idiom that dressage training should be there for the horse and not the horse for dressage. The goal of dressage is to improve horses. Remus is a very good example of what proper dressage, which not just meant for personal glory, an do to a horse challenged by his conformation.

Article by Silke Rottermann for Eurodressage.co

Photos © Elisabeth Weiland - No Reproduction allowed

Read more about Remus’ performances in:

- Josef Neckermann, Im starken Trab, Warendorf 1992.

- Harry Boldt, Das Dressurpferd,Lage- Lippe 1978

- Reiter- Revue (Hg.), Kavalkade Bd.11, Olympische Reiterspiele 1964, Mönchengladbach 1965.

Related Links

Mariano, the First World Champion in Dressage

Wolfdietrich, Chammartin’s Aristocrat

Antoinette, Josef Neckermann's Prima Donna