Lightness has, sadly, become rare on the modern dressage scene. We see huge trots (euphemistically called “collected”) and wonder why piaffe is so difficult to perform classically. The Dutch have removed the halt from their national tests “because it unbalances the horse” (a quote from Eurodressage.com). This regret- table new rule in one of the leading dressage countries has become necessary because too many confuse excessive speed with impulsion, so the engagement created by all that energy does not survive at low speeds, in halt and reinback.

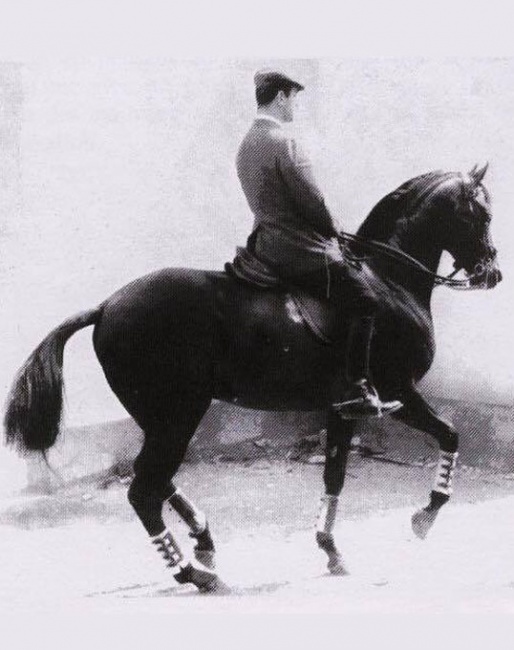

The balance of modern horses is compromised by too much leg, too much hand and too much noseband, all of which simply prohibit lightness. So a lack of lightness is the proof of lack of balance—and self-carriage. François Baucher’s last disciple, General Faverot de Kerbrech wrote, “Lightness well understood increases impulsion” because lightness comes from the absence of resistance that allows the energy to travel through the (relaxed) horse. The French ‘permeability’ and the German ‘durchlassigkeit’ are only possible with a horse that is supple, balanced, energetic and light.

In fact, we may occasionally see more lightness in show jumping and eventing than in dressage. The top riders in those disciplines certainly believe that giving the horse freedom of head and neck before and over a fence is the best way to jump cleanly and safely.

Showjumper Eric Navet, an Olympic medalist and European and world champion who has earned six World Equestrian Games medals, is at 57 still a top grand prix rider and considered by many to have the best hands on the circuit. When I asked him his opinion on lightness, he insisted “it is not enough to just have a light horse. To produce a horse that is light is not so difficult in itself. What

is more subtle is to get a horse that is engaged, pushes himself forward with a back in positive tension, with a locomotion that creates the sufficient propulsion to jump well. All of that must happen while he stays light on the hand. In a word: light but always seeking the contact.” This description implies a lengthened, relaxed topline with a strong muscular tonus.

Lucinda Green from Great Britain is a both a world and European champion, with three European team gold medals and an Olympic team silver medal to her credit. She won her first of six Badminton Horse trials in 1973. Forty years later, her impeccable cross-country style is both safe and elegant, and still amazingly efficient.

Her riding is characterized by the balance she fosters in her horses while allowing them the freedom to use their initiative. “While teaching, I am always trying to help riders have fingers that are sensitive to their horse's needs,” she recently explained. “There are times when they have to be so tight around the reins and times when they have to be holding a feather, giving in a split second to the horse's request for the chance to use his head and neck the way he may need it, either to see or to balance.”

It is important to note that Lucinda insists the firmer hand is never used to pull backward, but rather to occasionally support a horse needing it to get off the ground. Her release helps the horse use his front end to either see his way through a combination, recover his balance in front of a fence or, most especially, after a fence, when a light hand allows him to telescope out his head and neck.

Lucinda’s equestrian tact while riding cross-country reminds me of the lessons I received from Master Nuno Oliveira. He said to me once, “Sometimes the hand needs to be made of concrete and sometimes of butter, going from one to the other instantaneously, according to the resistance the horse presents or the release he just offered.”

ORIGINS OF LIGHTNESS

In the early seventeenth century, Pluvinel wrote that if a horse was prepared methodically to cooperate with his rider, we must then diminish all the aids, “so the spectators could say with truth that this horse is so gentle and well trained that he appears to work on his own.” The author of The Maneige Royal gives us a principle that is the key to training in the deepest sense of behavior modification: by progressively diminishing the intensity of the aids, we engage both the horse’s comprehension and his goodwill.

Progressively, the physical aids used to shape the horse’s movements will become mere signals designed to indicate our wishes. Self-carriage and self-propulsion as well as co-operation are the elements of the

complicity all riders wish to have with their horse. Eric Navet always says the winning horses are the ones ‘who take you to the fence while staying light.’They are easily controllable, yet moving forward in self-impulsion.

La Guérinière was the first to coin the phrase “descente de main,” a technique that consists of a quick abandonment of the feeling of the bit by the rider lowering his hand until the horse is completely free, as if “without a bridle.” Baucher and his followers Faverot and Beudant defined the concept further as a complete cessation of the aids while the horse maintains his gait with the same degree of energy.

SECRETS OF THE FRENCH EQUERRY

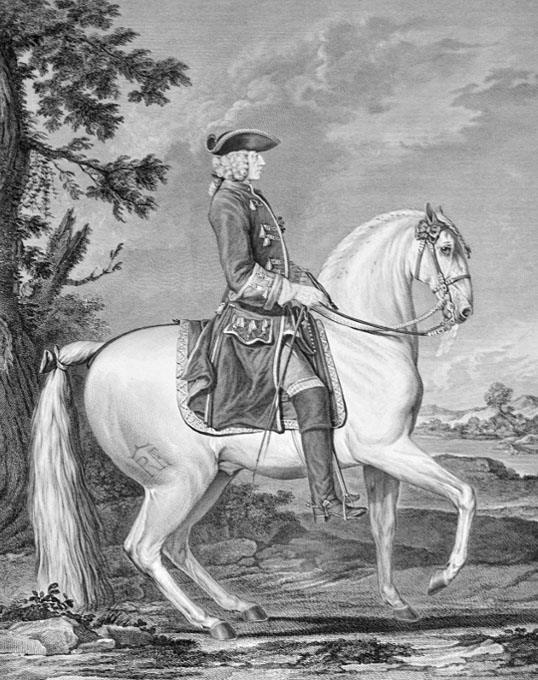

According to all who saw him, Nestier was perhaps the greatest rider of the eighteenth century. (As a result, an impressive rider was called “a Nestier.”) We know this through two pieces of information that need to be reunited to make sense. First, his iconic portrait on “Le Florido,” a precious Andalusian gifted by the king of Spain to his cousin the king of France. Le Florido is seen in the transition of halting on the haunches in the portrait, his top line rounded and the reins yielded.

What is remarkable in this picture is the bridle: it is one of the first representations of a double bridle. Le Florido’s mouth is relaxed and wet, thanks in part to the right hand softly placed on the right rein that vibrates the snaffle. (The snaffle’s mission is to relax the tongue. The curb, called “a la Nestier” to this day, is the first truly soft bit in equestrian history. The short branches have a rapport of one to one and the mouthpiece is jointed, making each branch independent of the other. This is a bit with practically no stopping power.)

The second piece of information comes to us through the writings of General Alexis L’Hotte, a famed nineteenth century horseman. Based on memoirs of the times, he tells us that Nestier rode out hunting every day, combining elegance, control and boldness, even on the most difficult horses. He was reputed to have had powerful legs and used their pressure close to the girth. (His hunting boots cut higher than the knee did not al- low him to bring his legs back very easily.) He controlled his horses by collecting them from the core and had no need for the leverage of the long curbs used by all his colleagues. He could gallop his horses and slow them down by using his body weight and the collection from his fixed legs (working as a point of leverage) rather than the forceful action of the hand on a powerful bit.

As the horse builds his core and becomes able to maintain collection on his own, the legs diminish their pressure intensity until it becomes a mere squeeze. The lightness Nestier could achieve with all the horses he rode came from a technique that was later explained and named by Baucher as “the effect on the whole horse” (l’Effet d’Ensemble in French), with the difference that Nestier was an outdoor rider, crossing all kinds of terrains at serious speed and always in company of hounds and excited riders.

L’HOTTE’S INFLUENCE

L’Hotte was also an excellent writer and scholar who understood the history of the art he was passionate about. In his retirement, he rode his three horses until his death at 77 and wrote two seminal books, A Cavalry Officer and Equestrian Questions. They offer a synthesis of the education he received from his two masters. Bauch- er’s dressage was all about control, balance and the resulting lightness, while D’Aure’s teaching was about the rider’s aids and position that could guarantee impulsion and solidity across country.

L’Hotte learned how to utilize horses practically, regardless of their level of training. Contrary to the ongoing polemic surrounding his two masters’ public rivalry, L’Hotte found the wisdom to advise his readers on the

appropriateness of each approach and to make sure they did not compromise each other’s benefits. The essential of the French dogma can be found in those fascinating books, including a comprehensive vision of lightness in A Cavalry Officer.

Here are a few excerpts from A Cavalry Officer, with my own notes in brackets for further explanation.

“The perfection we dream of, as much for the rider as for the horse, reside not so much in the performance of the ‘equestrian difficulties’ [jump- ing higher, doing complicated tricks or complex dressage movements], but rather in the purity of the movements [the gaits, as well as the correctness of the basic exercises].”

“This purity is achieved when the demands of the rider, as well as the effort of the horse, only use the effort necessary to the movement wanted, [in other words, never more force than needed by the rider, but as much as necessary; never more contraction from the horse as indispensable to the exercise]. To obtain a pure movement, it is therefore necessary to eliminate all the contractions that oppose it, that are not useful, in a word, all the ‘resistances’ [such as tightening of the back or retracting of the neck, or a lack of engagement or shoulder freedom]. The work that results is of a great delicacy and may demand the most diverse combinations of aids. This necessary inventiveness is what sustains the interest of the trainer in the accomplishment of even the simplest movements.”

“It is in the perfection that can be reached in the use of his muscular effort by the horse [the fluidity of the movement performed with energy and balance], as I just defined it, that resides the expression of the supreme lightness.”

“...At the end of his life, Baucher insisted on perfecting simple movements. He told me that ‘yesteryear, I used to quickly get into the complicated movements. Today I spend 6 months focusing on my horses walking straight and turning properly.’ [Pluvinel in 1600 already wrote that turning was the hardest thing to teach a horse, and I fully agree with this opinion; we spend a lot of time perfecting turns because the symmetry of turns greatly improves the ability of the horse to center himself and become upright, the basis for balance, and therefore greatly improving his

lightness of contact as well as reducing one-sidedness.]. He added: ‘It will be for you like for me. After trying all the difficulties of the art, you will find your greatest pleasure in the perfect lightness, however simple the exercise.’ And my master's prediction was correct. I have reached this point many years ago.”

“When the horse’s joints don’t resist any more [by re- fusing to flex or engage] nor stay inert under our demand, [lose their forward push], when all his parts can be put into play, be animated and vibrate [the word used by the French and the Portuguese to describe the intense and con- trolled energy of the collected horse] from the simple caress of our aids, [I am completely satisfied that] there is no further need to seek complicated [dressage] movements in order to feel infinite pleasures.”

“Those pleasures can be found instead in the refined feeling experienced by the rider. They originate in the elastic and soft flexibility of all the joints, animated by impulsion, within the harmony of the movement created by the correct use of the aids. In fact, they come from the lightness that is derived from it. [Lightness] is what stamps academic equitation and gives the trainer who practices it, the true character of his talent.”

LIGHTNESS IS RELATIVE

L’Hotte recognizes that different horses may require different training strategies. “By whatever method lightness can be achieved, it cannot be entirely maintained when we try a movement that the horse has not yet learned. The lightness will be altered without exception because many extraneous forces will first be put into play and it is only little-by-little that we will manage to extinguish them in order for the sole useful effort to subsist,” he wrote.

Lightness is in fact relative to each situation: new techniques, new exercises, new surroundings, new equipment, etc. will alter lightness for a time. It is a frequently heard dressage fallacy that the dressage of a given horse will be achieved in total lightness from beginning to end. Even the greatest lightness advocate recognizes this as impossible.

APPLYING HISTORICAL WISDOM

L’Hotte’s teacher, Baucher, warned him that, “when complete lightness is obtained walking in straight lines, the pleasure resulting from the harmony [the marvelous lightness of the horse] felt by the rider is such that we could hesitate to progress to [faster or more complicated] movements that may unsettle this perfect equilibrium.” Lightness is addictive and generations of Baucher admirers suffered from the temptation to search endlessly for perfection of equilibrium in short gaits at the risk of losing impulsion.

As proven by Nestier and his bit, the more appropriately the legs are used in combination with weight effects, the less the hand is needed. The horse’s roundness and balance as achieved by Nestier guaranteed control, safety, soundness and longevity; the horse moved in an ideal harmonious way.

This understanding of the use of the legs to collect the horse at any speed is missing in dressage and, for that matter, in other equestrian sports today. It is the main reason we see horses neither truly collected nor calm, who cannot halt properly and stay immobile and instead fidget at X in all too brief “halts” in which nobody has even the time to salute with dignity.

Dressage horses must demonstrate proper self- carriage and goodwill. Reading classic dressage books written by those who spent a lifetime training horses is indispensable to any rider wishing to acquire as much

knowledge as possible. Attempting serious dressage, which is always difficult, without reading— and re-reading—Steinbrecht, Oliveira, La Guérinière, Decarpentry and L’Hotte (all available in English translation) is like trying to get into the famed Massachusetts Institute of Technology without first learning high school algebra.

Part 2 of The History and Biomechanics of Lightness is here

by Jean-Philippe Giacomini - First Publishes in Warmbloods Today

Related Links

The Shaping of Piaffe and Passage by Fashion, History and Genetics: Part I

The Shaping of Piaffe and Passage by Fashion, History and Genetics: Part II

The Shaping of Piaffe and Passage by Fashion, History and Genetics: Part III

Mastering Lightness: Understanding the Biomechanics

Mastering Lightness: The Correct Piaffe