Chris Hector, editor-in-chief of the Australian Horse Magazine recently visited Gestüt Lindenhof, the home of Georg and Monica Theodorescu, and received a heart-warming welcome. Hector and his wife Roz Neave were able to get a feel of the daily routine and a look into training of the horses in the life of the Theodorescu's. "George and Monica Theodorescu are cultured, refined people, and they ride and train just like that," Hector summarized.

Here is Chris's story of his walk on the premises of the Theodorescu's...

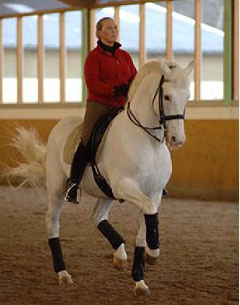

On the morning we visit, George is wandering around with his long whip, dispensing carrots and nuggets of wisdom, while Monica has her horse, Whisper, going in such a perfect self-carriage that it is breath-taking. Even when the horse kicks up against the whip when asked for a little more in the piaffe, his neck and nose remain in perfect position – the neck stretching up out of the wither, the nose just a touch in front of the vertical, and that is where it has been all working session. Later I remark to Monica that this does not usually happen… she seems to think it is normal.

“If I ask a little more behind, he has to have the possibility to go forward, so I definitely don’t pull back.”

That’s the theory, but it doesn’t usually happen that way. Usually when people are having an argument with a horse they end up losing their nice outline…

“The horse always has to have the chance to go forwards, always. Even if you ask a little more behind or say, hey, wake up a little, he has to have the chance to go forward, and never be afraid.”

He never ever came behind the vertical…

“I don’t see it but the contact that I want to achieve is from pushing the horse from behind, from getting it active and engaged behind, through its back, through the neck and then into the contact. But never ever is the contact from the front to the back, that is why he shouldn’t be behind the vertical. I want a contact; he’s not light because then he would be behind the bit and behind the vertical. I had a contact at all times but it is up to me how much, or how little. He is at the stage where he has enough self-carriage. I don’t have to carry him, he is coming under enough, and he is strong enough. The half halts really get easy and come to a suppleness so he is light in front, but I still have a contact.”

When we arrive Mr Theodorescu is finishing a training session with the Russian team member Alexandra Korelova and her horse Balagur. The pair were a sensation when they appeared at Aachen in 2005, then came back in 2006 to finish a remarkable 7th at the Aachen CHIO that was held in May to leave the traditional space for the WEG. Then it all fell apart for poor Alexandra, who having returned to Russia, found that she could not get a visa to return to Germany – and her horse! Finally after the intervention of the WEG boss, the rider arrived at her trainer’s barn in Germany, ten days before the World Championships were to begin, and with no opportunity for warm up competition. Not surprisingly, they didn’t do all that well…

Alexandra is now free of her visa troubles and working at the Theodorescus, and she and Balagur look to be hitting top form in the lead up to the European Championships in Italy in September.

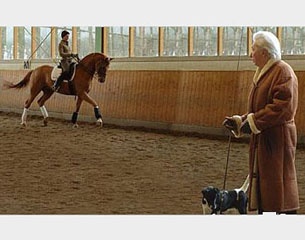

When you visit Gestüt Lindenhof there is a comforting familiarity, the dog population is always the same. There is always a French Bulldog, that belongs to Mrs Theodorescu, a Greyhound that belongs to Mr Theodorescu, a Fox terrier that belongs to Monica, and the Rottweiler guard dog. The cast may change with the passing of time, but the characters remain the same, and Terry – Monica’s new young ‘terror’ – is a real character. She keeps appearing in the arena with carrots she has filched from the horses.

“She is a cannibal,” Monica remarks, “The worst thing is when she gets a carrot and then eats it in front of a horse cross tied in the stables.”

Carrots play a large part in the daily life at Lindenhof – Mr Theodorescu always has a pocket full, and a knife to cut them into horse sized chunks. “People say to me, ‘I would never do that – never give the horse carrots, they must do what I tell them, they must do it’. Why? When you ask them something new, they are a bit afraid, but if they like you, they know your voice, they know you have something for them, it makes it easier. They are very intelligent, we’ve got to find a way to talk to them.”

As Monica rides around the hall, the little dog runs in front of her, every four or five strides it just puts in a leap of joy, like a little deer. Finally Monica shoos her away and Terry decides that my lap looks a workable alternative.

Where the dogs sit is an important consideration round here. One time, two dark suited reps of the local Mercedes dealer, arrived with the latest, greatest model, and on a special special price for their good customer, Mr Theodorescu. He took one look, “but there are bucket seats in the back, my greyhound will not sit on bucket seats, bring me one with a bench seat.” “They don’t make this model with bench seats.” “It is a very nice car, and a very generous offer, but please take it back then.”

George Theodorescu’s unique equestrian philosophy is the product of what he learnt first in his native Rumania, but also later when he found himself in Germany:

“I had the chance in Rumania to work with a very very good trainer, then when I came here, everything was so organized, the shows, the classes… even in Germany now many things have changed, but in the past I think things were more serious in the way people worked the horses – and also the test. Today everybody says we don’t have much time but when I came to Germany, the Grand Prix was 16 minutes long – now it is seven minutes. They say it must be shorter because we don’t have the time, but with horses if you don’t have the time, then better you don’t do it.”

“The horse has four legs, that is our problem as riders. We have a very different balance, people on two legs, and the horse on four legs. The rider can turn like a soldier, left to right, with horse you have to make a turn, and that’s the problem that is in no other sport. The horse and the rider, with such different balance, and the two must arrive to the same balance, that takes talent and work. If you look at the high wire artist in the circus, if they want to make it harder, they put another person on his shoulders, and if that person makes a mistake, they both fall down. But they both have the same balance, the same rules: the horse and the rider, they have completely different balance.”

Meanwhile, Alexandra has got off Balagur, and decides that he needs to walk around the school a few times to cool. She throws the reins over his head, and as she walks off, whistles, Balagur follows behind.

“He is such an intelligent horse,” George muses, “At Athens I was not allowed to work with a whip from the ground in the warm up, so I took out my handkerchief, and waved it in rhythm, the horse responded as if I had my whip. The steward came running over and said, you must not use a whip! Where is the whip? I asked.”

Whisper is a good deal bigger and a totally different style of horse from the charming little grey Trakehner mare, Fleur, who Monica lost so tragically a few years back just as she was beginning to win World Cup classes, but both horses share the same quality of absolutely pure rhythm and regularity of pace.

Again, Monica seems almost surprised that anyone would mention it:

“The rhythm, the cadence, has to be the same all the time. Trot, left, right, half pass, circle, the trot has to be the same all the time. That makes it easy for the horse to carry himself. And of course the half halts, which maybe you don’t see, because the half halts should not be seen… but when I ride I probably do a few hundred half halts in a lesson with one horse. I see it in clinics, you say half halt, people just pull and then go again. The horse has a little break and then goes again, there is an interruption in the rhythm – and I say, that’s not a half halt, that’s just pulling. A half halt is first you engage the horse from behind, then you just don’t let it out for part of a second, but you still ride with the horse. You never interrupt the rhythm. First you have to engage, the horse comes under, then you do the half halt by keeping the horse on your legs and position and not letting it go again. You feel the horse getting soft in the back and the neck coming up into the contact. That’s a half halt. But you never disturb the rhythm.”

“If someone tried to put the horse’s head right down to the chest here, I would say, jump down off the horse, I don’t want to see that,” George says. “It is a sacrilege to ride like that. Too much of anything is not good. Too much red wine makes a mess of the table. Riders ask too much, it is better to make haste slowly. See this half pass of Monica and Whisper, it is like a dance, the half pass must be like a dance. Sometimes people will say to me, look at this half pass, there is so much crossing – but it looks like an epileptic fit: it must be a dance.”

“Now in dressage the problem is that most of the riders, think they don’t have time, and they think they should be quicker. If you don’t have time, don’t ride. You need talent, but you also need patience, you must see the horse like a best friend, not like a machine.”

“In the past we were working the horses together with the judges, especially in Germany, the judges mostly came from the Cavalry, and all their lives they had horses, horses, horses, they worked with horses. In the end you got the protocol from the judge with your mark – what you did wrong, what you did right and what you have to do to be better. If we had a show over three days, then we could make it better from one day to the next. We were working the horses together with the judges. Now we have judges from all different countries, and they give only marks, and we don’t have this protocol any more. Now the riders are confused, one judge gives three, the other judge gives eight – now you can’t change, because if you do what one judge says, you will have a problem with the other judge. The judges should show the way with your horse, they should help you, not just give the marks. How can you learn when one judges says this is white, and the other ones says, this is black?”

Now Mr Theodorescu is working with the American rider, Dennis Callin and his American bred Holsteiner, Ruskin. Mr Theodorescu is one of the masters of whip work from the ground, but the first task is to get the horse so that it is unafraid of the whip. Apparently when Ruskin first arrived in the hall, he was terrified of the whip, now he accepts it and the piaffe work is getting better and better.

Monica finishes the work with Whisper and lengthens the rein and the horse stretches without hesitation, out and long. Monica has had the chestnut since he was a four year old: “I saw him a little earlier than that, at Ann-Kathrin Linsenhoff’s place. It’s her horse.”

And you get to ride him forever???

“After one or two months, we sent the grey back. It was very nice, a little bit more advanced than Whisper, more balanced already, but I thought he was more limited. That’s how Whisper came here.”

What attracted you about him?

“The walk was already very big, the trot was quite normal in the beginning because he was really on the forehand. But I liked the cadence he had, even though he wasn’t showing much, not very expressive, but the cadence and the suppleness in his movement. He was kind of funny with the boys working here at the time. We didn’t have much of a rider for young horses… he used to put his head down, run off at the wall, and then decide left or right and they would fall off – that’s what he did at Ann-Kathrin’s too. He wasn’t that he was stupid, just them hanging on to the reins, and he could get rid of them. When he was four and a half, I started riding him daily. He didn’t do it with me.”

Do you lunge your horses in the over-check?

“It depends on the horse, it depends on what they need. We lunge also with long side reins so they find the contact and the balance, whatever the horse needs. Some need to have the top reins, others, they have to stretch down.”

With Whisper?

“I didn’t do much lunging with him when he was young. Later when he was seven I lunged him with the top rein.”

The Theodorescus head rider, Ike Hahn has been with them for twelve years now, and he too, rides lightly, tactfully.

George likes Ike’s attitude to the horses. “He had only been with us for three weeks when someone sent us a chestnut horse. I said, here, let’s see what he is like. Ike rode him into the school, and the horse took one stride, then put his two front feet up on the ledge of the school wall. Ike didn’t get mad. He said to the horse, ‘why are you doing that, don’t be silly’. Then he just swung him around, the horse put his feet on the ground, and took another two steps, and he put his feet on the ledge again. Ike never got mad at the horse – that I like.”

Despite a life-time training horses, Mr Theodorescu says he still enjoys his time in the Riding Hall: “Always. For me it is very interesting, the horses they are very different, like the people. Sometimes I have had big success with horses that could not even finish the test with another rider – you must work with these horses and get their confidence. The confidence is very important because the horses are always afraid of something new, and if they have had a bad experience, you need a lot of time and patience to convince the horse that everything will be okay.”

Out the back in the old indoor, Dennis is lunging his Fürst Heinrich filly – and, as often the case here, lunging her in an over-check. This I remark to Mr Theodorescu that this way of lunging not so common in a world obsessed with getting horses as low in front as possible:

“We have had very good experiences with the horses working like that because the young horse – three or four years old – has in front more weight than behind. Say the horse is 480 kilograms, cut it in two, and they have 280 in front and 200 in the back. To put the horse in balance through exercises and in time, you put the weight on the haunches, on the hindlegs. If you have enough experience to work with lunging in the over-check, over time, in a couple of years, you put the horse’s weight at the back – you put the horse in balance.”

“The work has to be done only by someone who has experience with this equipment, how much you tighten up the side reins and the over check is very important. It needs horse people to understand the balance of the horse’s body. On the lunge line you have the advantage that you always have the horse in front of your eyes so you can see the muscles, the power, the weakness, and how much this side rein / over check needs to be adjusted, how much sideways, how much down, how much up. Horses are like people, they are not all equal, you cannot say it must be exactly this long or this short – if you have eyes you can see where the weakness is, and help the horse. The advantage is that there is no weight of the rider in his back, no one pulling on the rein, so for the horse it is much easier to put the weight on the haunches and to get in a balance.”

For Monica, the work with Whisper has finished for the day, but the big challenge is just down the track: is Whisper the next German Team horse for Monica?

“I don’t know. I hope so.”

And it doesn’t have to be spectacular – the judges will be happy to see correct work?

“Why not – otherwise I shouldn’t be doing it.”

And the question I’ve always wanted to ask – why do you ride with your stirrups so long?

“My stirrups are long because I like to pull up my knees and my heels. I like to have them longer to search for the contact, to keep my legs long… I shortened them today for you.” And we all laugh and bid farewell. Until next time, and hopefully, there will always be a next time, because the atmosphere in some stables is always special.

Article courtesy Chris Hector - The Horse Magazine