Undoubtedly in modern day dressage the ground quality of the horse plays an ever increasing role to be successful. One can regard this fact either as the triumph of modern warmblood breeding or as a danger to the quality of training and riding.

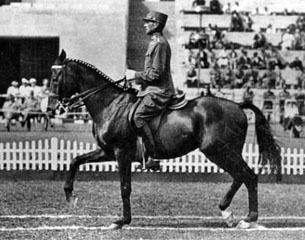

With the tremendous improvement of the breeding of dressage horses over the past decadesn one can also observe the disappearance of the pure Thoroughbred from the discipline. In the past this breed has provided many beautiful dressage horses on the international dressage scene, amongst them Podhajsky's legendary Nero xx.

More than 70 years ago the situation was different as the period between both World Wars was dominated by riders of the cavalry, competing on military owned horses; many of them Thoroughbreds. Today they would no longer be considered suitable for dressage. The military in Europe before World War II couldn’t afford expensive horses and moreover did not buy horses for dressage purposes alone. Instead the officers had to work with horses assigned to them and they tried to bring the best out of them with dedicated work according to the classical principles. Among those horses there were thoroughbreds unsuccessful on the race-course and which could be bought cheaply by the cavalry.

A failed race- horse joins the Austrian military

Such a horse was the bay German bred Thoroughbred “Sindbad” xx, born on 19 May 1927. His breeder W. Welp had bred him by the famous thoroughbred Dark Ronald xx with the intention for him to go on the race track. An Austrian bought him for the proud sum of 10,000 DM, but like so often high expectations could not be fulfilled and Sindbad disappointed in the races. His owner lost interest and offered him to the Austrian military. For only 2000 Austrian Schilling the narrow and leggy thoroughbred changed owners.

Renamed “Nero” after the Roman emperor he was subsequently stabled at the riding instructor institution of the Austrian military. They aspired him to become a good jumper or a dressage horse, but Nero soon dashed all hopes. For jumping he was far too coward and for dressage he lacked impulsion and willingness to go forward. The Austrian military hadn’t done a good business and didn’t want to keep him because such a horse only cost money.

Finally in 1933 Nero xx was offered to one of the best dressage riders of the cavalry, Alois Podhajsky, who had already trained average military horses to become international successful ones in dressage. Podhajsky reported in his book “Meine Lehrmeister die Pferde” that he didn’t mind Nero’s past nor his very moderate looks. Instead he was happy to have another horse to train in dressage.

During this time Podhajsky was attached to the Spanish Riding School (SRS) for two years and nobody showed any enthusiasm when they saw his latest assignment from the military. While Nero was neither beautiful nor impressive in any way, the same could be said about Podhajsky’s mare Nora, an Austrian warmblood which made him an international successful dressage rider at the time.

”Beauty is always an advantage, but training a horse strictly after the classical principles we followed at the SRS can transform the ugliest horse into a well muscled athlete. Nero was a superb example and proof of it," said former SRS Oberbereiter Georg Wahl. The legendary Wahl was scouted and taken to the SRS by Podhajsky in 1939. Podhajsky was convinced he could transform the thoroughbred did have good movements.

Teaching a Thoroughbred to Move Forwards

When Podhajsky took Nero over he was stabled in the “Wilhelm Barracks” in Vienna where both his horses were housed. There, soon after Nero’s arrival, the gelding spent the whole night chewing Nora's tail. Not only did Nora not look very charming with her bald tail, but even worse Nero got jaundice and was ill for over a month. It was not a good beginning for the new partnership, but when Podhajsky took on the work he soon noticed that the horse bred to run was not keen on moving forward.

Working him in a fenced arena would have made everything worse, so Podhajsky took Nero for long hacks to the “Prater” in Vienna, a huge park with forests, fields and rivers. He avoided to ride curved lines or turns, but instead took care Nero on long straight lines. At the beginning Nero didn’t like to see open fields, obviously reminding him of the race-track. He became nervous, but after some time he got used to it and his impulsion improved more and more through these extensive hacks. After some time his rider dared riding Nero for short work outs in a fenced outdoor arena, but continued riding only straight forward, taking care that Nero maintained the impulsion. At the beginning Podhajsky only did rising trot and interrupted it just for short periods of sitting in the saddle. As soon as Nero lost his impulsion he changed to rising trot again.

Working him in a fenced arena would have made everything worse, so Podhajsky took Nero for long hacks to the “Prater” in Vienna, a huge park with forests, fields and rivers. He avoided to ride curved lines or turns, but instead took care Nero on long straight lines. At the beginning Nero didn’t like to see open fields, obviously reminding him of the race-track. He became nervous, but after some time he got used to it and his impulsion improved more and more through these extensive hacks. After some time his rider dared riding Nero for short work outs in a fenced outdoor arena, but continued riding only straight forward, taking care that Nero maintained the impulsion. At the beginning Podhajsky only did rising trot and interrupted it just for short periods of sitting in the saddle. As soon as Nero lost his impulsion he changed to rising trot again.

Alois Podhajsky, who later became the most famous leader of the SRS of all times as well as an international judge and author of well known books, always emphasised the importance of maintaining good impulsion to develop all collected movements. This principle worked with Nero too and after some months the horse wasn’t lacking drive anymore and could be worked in dressage more seriously. Podhajsky realised the great intelligence of his new horse who turned out to be a quick learner. Aware of the great importance of praise to motivate a horse he finished the training and sent Nero off to the stable after every progress in a session. Nero had to correlate work with comfortable memories.

Starting an International Dressage Career

After about eight months of training, the 6-year old Nero was able to compete in his first dressage show, an M-class in Vienna, where he placed second behind his stable mate Nora. Despite the quick progress Podhajsky still had to overcome other problems in Nero's career: hoof issues. The thoroughbred’s petite hooves tended to be fragile and his thin soles predestined him for inflammations. Podhajsky reported that he often had to interrupt his training for weeks because Nero was unsound.

During the training Podhajsky had to be aware that his horse was a “morning grouch” and always needed extra time to warm-up early, but then he was working very eagerly.

In the 1930s there were no championships like today, the sport was still in its infancy. Between Olympic Games the FEI hosted so called “FEI championships” at Grand Prix and Prix St. Georges level. In 1934 the Swiss military horse depot in Thun hosted the annual championships and Nero was selected to travel there to represent Austria, along with Nora. Podhajsky again had troubles with one of Nero’s hooves. A Swiss farrier had to construct a special shoe which he tacked down with just one single nail. To guarantee stability the farrier instead welded three caps (instead of the usual one or two caps) to the shoe. The shoe stayed on Nero’s fragile hoof this way, but it was much heavier than the other one which caused him to move irregularly at the beginning. Soon the horse learned to compensate and trotted perfectly sound in the competition itself, in which he wasn’t as successful as Nora, who placed third behind the winning duo German major Friedrich Gerhard on the massive Fels, the complete opposite of Nero.

Only a year later Nero, who hadn’t really enthused the international judges and public, won the 1935 FEI Championships held in Budapest where thirteen riders from four nations competed. He won ahead of two of Germany’s best dressage riders, Hermann von Oppeln and Friedrich Gerhard, both from the German Cavalry School in Hanover. Of course, the number of starters in those FEI championships indicate that the international dressage scene in Europe was very small compared to today. Unlike today there was no serious opposition from overseas the top in Europe was the top in the world. It must have been an encouraging win for Podhajsky on a horse which had been given up on two years before.

Olympic medalist 1936

1936 was an Olympic year and Austria sent a whole team to Berlin where the Nazis has organised Olympic Games under the shadow of the schwastika.

For dressage it turned out to be a very successful Olympics with a record number of nine participating teams, among them Hungary, Norway, the Czechoslovakian Republic, and the USA.

Of course Nero was among the favourites, but the Germans had different horses than a year before, in particular the black Trakehner geldings Kronos and Absinth which were bred by the same breeder and close relatives. They were serious medal contenders.

Of course Nero was among the favourites, but the Germans had different horses than a year before, in particular the black Trakehner geldings Kronos and Absinth which were bred by the same breeder and close relatives. They were serious medal contenders.

Before thinking of any medals Podhajsky had to solve a problem of another kind first. That time it weren't Nero’s hooves, but his sensitive character which caused problems, for example when flowers decorated the arena. In Berlin it was the white lines on the green grass of the dressage arena which he had suspiciously observed, spooking and jumping over them. Podhajsky managed to get the same white lines in the warm-up arena and allowed his horse to observe them as long as he needed to.

On the day it counted the thoroughbred didn’t mind them and executed a very good programme. Compared to the wonderful Trakehner horses of the Germans Nero was a bit less charming, but with no videos available the judgement remains vague.

In the end Nero xx got the individual bronze with the Austrian team finishing fourth. Twenty-four points separated him from silver, 38,5 from gold which was won by the young German Heinz Pollay on the beautiful Trakehner Kronos, trained by Otto Lörke. Not very surprisingly the Austrian judge Colonel-lieutenant von Henikstein had placed Nero 1st. And not less remarkably the German judge, General von Poseck, put him worst, seventh. However, the legendary Gustav Rau mentioned in his book on the 1936 Olympic equestrian events that Nero also had won the bronze medal without the Austrian judge. The major achievement, however, was retraining the horse from scratch and putting it on an Olympic podium in three years time.

Nero, A Force to be Reckoned With

Only a good week after Berlin many of the Olympic competitors met again at the holy grounds of Aachen for an Olympic revenge. Nero xx used the opportunity and won the Grand Prix ahead of the rest, though he had to do something he disliked very much in his early days with Podhajsky: jumping. It was part of many dressage competitions to jump a small obedience fence at the end of the dressage programme. In the early Olympics dressage horses even had to jump over a pole rolling towards them!

Nero had always been frightened of jumping and Podhajsky could never practise it extensively because of his fragile hooves. Nero overcame his fear of jumping by being allowed to observe every fence as long as he wanted to and by seeing other horses jump. At Aachen in 1936 Nero hadn’t been jumped for about a year and to confirm his win he had to jump the fence what he obediently did. Podhajsky considered this a proof for the extraordinary faith his horse had developed through his training and the obedience achieved through it.

In 1937 the thoroughbred, who had become quite an attractively muscled horse through his classical training, returned to Berlin for the FEI championships, but was beaten by the Olympic silver medalists Gerhard Friedrich on the Trakehner Absinth. The FEI strangely decided in a conference at the end of 1936 that only horses 14 or younger are allowed to take part in FEI Grand Prix classes, something incomprehensible today and a rule which eliminated some nations with less strong horses from international dressage competitions. The 10-year old Nero was luckily untouched by this rule.

In 1938 the horses, which usually travelled by train, had to board ships to bring them to the FEI championships in London. Nero participated in his fourth championships and his rider had to wear the uniform of the German Wehrmacht as Austria had been annexed to Hitler’s Third Reich in March. Unfortunately Nero couldn’t live up to the expectations and placed fifth in a field of 11 riders from 4 nations. The French André Jousseaume won on the highly noble petite Anglo-Arab mare Favorite, an old rival of Nero from the Berlin Olympics.

Like most great horses Nero had his special habits. He might hadve shared his love for lumps of sugar with countless other horses, but his cleverness allowed him to collect them for the benefit of the amount! Instead of chewing them he stored the lumps of sugar in his mouth, like hamsters do. Often he succeeded and got several lumps of sugar because his rider or his fans thought he had missed the one before! Podhajsky saw sugar as an indicator for his horse’s state of mind. Like the legendary Josef Neckermann later experienced with his top horse Mariano, Nero refused taking sugar when he felt treated unfairly.

Last Triumph and Forced Career End

Nero’s career was finished because of the outbreak of the Second World War. Shortly before he had been on a longer tour of shows in Germany, competing in Verden, Hanover, Münster and Munich before he travelled to Insterburg, a horsey town in East-Prussia in August 1939. Shortly after his arrival Podhajsky discovered his horse swaying in his box and called the vet. He diagnosed the feared sporadic exertional rhabdomyolysis.

This serious illness inflames the back muscles, causing poisoning in the whole body if not treated immediately and effectively.

The vet used a very old, yet effective treatment, blood-letting, and he gave Nero injections.

He improved, but Podhajsky took all precautions and the groom led the horse to a nearby river to cool down his sensitive hooves. In the end Nero was able to take part in his very last show and won the S-class. Nero's career ended when the horse was 12 years old. However, without knowing the thoroughbred would play an important role again many years later.

Nero’s Contribution to the Rescue of the Lipizzans

Podhajsky became commandant of the SRS in 1939 and remained its leader until 1964. When he joined the SRS again he took two horses with him, Nero and a highly blood influenced Hungarian called Teja, which would become his 1948 Olympic horse.

”Podhajsky had Nero and Teja with him at the Hofburg stables. Both horses looked quite similar, but to me Nero was always the more outstanding dressage horse,” Georg Wahl remembered. ”When we went out hacking the Lipizzans in the Lainzer Tiergarten in Vienna, Podhajsky would often take Nero to lead us," Wahl added. The thoroughbred looked so different from the grey Lippizans.

Podhajsky was lucky to keep his beloved horse through the most difficult war times in Vienna. Of course Nero was evacuated at the end of the war, when his rider commanded the evacuation of the SRS because of increasing bombings of Vienna and fear Russians might occupy it. The evacuation became legendary to that extent that Walt Disney produced a movie on it. The late Georg Wahl, who was probably one of the last surviving witnesses alive during an interview in 2011, was among the riders who took part in it. “The evacuation was less dramatic than often assumed, in particular not as dramatic as in the American film about it. We knew what to do back then," said Wahl frankly.

The Lipizzans and Nero got a new home in a small village in Upper Austria, though they still weren’t completely rescued. It was uncertain what would happen with them after the war was over and the allied took control of the country. When the US troops liberated the country and marched in the streets, one US major discovered Nero in the stable. He had seen him compete in Berlin in 1936 and recognised the great horse. He remembered his stunning performance almost a decade ago.

So Nero’s discovery was the beginning of what became the legendary rescue of the Lipizzans and their School. The major helped Podhajsky to contact the US troops. General Patton, who was a former Olympic pentathlete in 1912, agreed to put the SRS under the protection of the US troops.

”When Nero was already over 20 he still looked very well and practically hadn’t aged," Wahl stated. Podhajsky had ridden him the last time when the horse was 18. The rider then thought that his old companion might like living in big fields during his old age. He gave him to the place where the Lipizzan brood mares had found a temporary home. Unfortunately the opposite happened. Nero suffered from being separated from his usual environment and was very excited seeing the mares and their foals. Instead of grazing peacefully he couldn’t calm down. So in the end Podhajsky took his dear friend back home to the Lipizzans, where the great old horse remained until his death in 1953. Nero had to be put down at age 26.

Podhajsky went on to become the probably most charismatic leader of the SRS ever, re-establishing the School after the chaos of World War II. But his master piece as a competitive dressage rider will forever remain this German thoroughbred Nero who, thanks to his mastership, transformed from an average looking horse nobody wanted to work with into an Olympic medal winner. Like many other horses of that time Nero was the proof that classical dressage training can improve horses and make them more beautiful, no matter their original talents and looks.

Article by Silke Rottermann for Eurodressage.com

(as told by Georg Wahl in 2011 and by using the listed references)

References

- Max E. Ammann, Buchers Geschichte des Pferdesports, Luzern and Frankfurt / Main 1976.

- Max E. Ammann, The FEI Championships. The history of World, Continental and Regional FEI Championships, Lausanne 2007.

- Alois Podhajsky, Mein Leben für die Lipizzaner, München 1960, p. 107 – 111.

- Alois Podhajksy, Meine Lehrmeister die Pferde. Erinnerungen an ein großes Reiterleben, Stuttgart 2011, p. 98 – 111.

- Gustav Rau, Die Reitkunst der Welt an den Olympischen Spielen 1936, Hildesheim 1978.