Helsinki Central Park, this green heart in Finland's capital is still a place where stressed modern minds can find some hours of recreation. Sixty-four years ago the peace of this narrow wooded oasis next to Ruskeasuo, a suberb of Helsinki, was disturbed by the sound of saws and hammering. The preparations for the equestrian events at the 1952 Olympic Games had began with the renovation of the old stables of the Ruskeasuo riding centre.

Soon after a dressage stadium was prepared in a wood-glade nearby the equestrian facilities. Stands were erected around the grassy rectangle and a roofed building created to house the five men who would decide on Olympic glory or a failure a year later. What sounds a bit amateurish in our days, became one of the most idyllic Olympic dressage arenas ever, fairly equal to the picturesque ring in front of the Nymphenburg Castle in Munich 1972 or the one in the park of the Villa Borghese in Rome 1960.

Post War Preparations

With the help of their army the Finnish were in full cry providing the best equestrian facilities possible. At the same time it was completely uncertain for many riders and their horses if they were to make it to Scandinavia a year later. Whereas today Olympic preparations practically start immediately after the last Olympic Games, back then the situation presented itself completely differently.

Three years after the end of the second World War the London Olympics had been held. The situation in dressage was still tense. The FEI had wisely decided to only ask a reduced programme for the 1948 Olympic Games, excluding the most demanding Grand Prix movements like piaffe and passage because it rightfully seemed impossible to have enough horses being able to show them so briefly after the war. The war had led to cavalry schools in Europe, such as Hanover, Strömsholm and Saumur to come to a forced stand-still. Their former glorious representatives partly lost their lives in the battlefields throughout Europe. Also dressage horses with the ability to perform a Grand Prix had been lost during WW II or had disappeared when the allies occupied Germany.

To take all that into account the FEI decided in 1950 that from now on also civilians and officers were allowed to take part in the Olympic dressage classes; more so even though they had already allowed amateurs to qualify from 1938 onwards, women were excluded and only allowed after the revision of the rules in 1950. So the basis of riders and horses available for the next Olympic Games was broadened.

To take all that into account the FEI decided in 1950 that from now on also civilians and officers were allowed to take part in the Olympic dressage classes; more so even though they had already allowed amateurs to qualify from 1938 onwards, women were excluded and only allowed after the revision of the rules in 1950. So the basis of riders and horses available for the next Olympic Games was broadened.

While this attempt seemed logical, the reality was rather a sober one a year before the first Olympic Games after the war in which the Grand Prix was required again. Germany had lost its brilliant cavalry school of Hanover, Saumur tried to revive its competition stable after the school was evacuated during the war and the USA had to recruit the first all-civilian team in their history. Only Sweden was able to maintain its strong position with its cavalry school of Strömsholm still working smoothly. Also Switzerland, widely unbothered by the consequences of the war, prepared some army horses for Helsinki after their representative Hans Moser had become Olympic Champion at London 1948.

To understand the level of competition which happened at the Olympic Games in Helsinki 1952, it seems helpful to allow a view on the preparations, in particular those of two female debutants.

The USA: The first civilian team, their first Olympic equestrienne

Very unlike Germany the USA couldn't be considered a dressage nation until the late 1970s and even then it relied more on single outstanding pairs than a broad basis like today. Their team medals in 1932 and 1948 shouldn't mislead as they were won under special circumstances and not against the best nations. But in 1951 the USA was additionally confronted with a special challenge as it was the time of transformation into the civilian USET (United States Equestrian Team) after Harry Truman had closed down the cavalry in 1949.

The country was practically lacking everything in dressage: trainers, riders, horses, media attention as well as financial backing. However, some German „imports“ helped solve the situation. The Westfalian Fritz Stecken, brother to Albert and Paul Stecken, had immigrated to New York in 1947 where he settled down teaching dressage in Scarborough at the equestrian department of the famous Sleepy Hollow Country Club. He had shipped his Westfalian stallion Nobel over on whom he also gave displays and taught students the advanced movements. He imported several German bred quality horses which the US troops seized during the end of the war, among them former dressage horses of the cavalry school of Hanover and Krampnitz.

The country was practically lacking everything in dressage: trainers, riders, horses, media attention as well as financial backing. However, some German „imports“ helped solve the situation. The Westfalian Fritz Stecken, brother to Albert and Paul Stecken, had immigrated to New York in 1947 where he settled down teaching dressage in Scarborough at the equestrian department of the famous Sleepy Hollow Country Club. He had shipped his Westfalian stallion Nobel over on whom he also gave displays and taught students the advanced movements. He imported several German bred quality horses which the US troops seized during the end of the war, among them former dressage horses of the cavalry school of Hanover and Krampnitz.

Unfortunately for the 1952 Olympics most of these ready-schooled horses were too old. But one younger horse, a most beautiful Trakehner chestnut was assigned to Captain Robert „Bob“ Borg, then the United States' top dressage rider among few of Olympic standard. He and Bill Biddle were first choice for Helsinki, but the other two team riders couldn't be more different.

It seemed hard to believe, but while Helsinki prepared its equestrian facilities a 20-year old girl, who would compete there a year later, started to get in touch with dressage. Surely Marjorie Haines had ridden from childhood, as her aunt owned a riding school where she competed quite successfully in jumping and had also occasionally evented, her first tender touch with dressage. Just graduated from art school, Haines got hooked when she saw a photo of Fritz Stecken on Noble. She was driven to find out more about dressage and took lessons from him. Hard to imagine nowadays she set her sails for New York with 1,500 dollars in her pockets and started working with Stecken. Living on an extremely tight budget, she still ran out of money very soon and was only able to continue because one of Stecken's wealthier pupils supported her in different ways. Marjorie also gave sewing lessons.

Even though Haines had to sacrify a lot, luck would come her way. Among the horses Stecken trained there was a very well built attractive Hanoverian liver chestnut called The Flying Dutchman, one of those seized horses that were shipped over at the end of the war. First successfully competed in three-day-eventing, the gelding was given to Stecken to be trained for Grand Prix.

When the first ever Olympic U.S. dressage trials were held on 1 April 1952 at Sleepy Hollow, Stecken sent Marjorie Haines on The Flying Dutchman. It was a decision not really undisputed as the equestrian scene, even though civilian now, continued to consist of many former army riders, totally male oriented. A woman on an Olympic team wasn't something everybody was enthusiastic about in those times, but Haines was nominated alongside Borg and Hartmann Pauly, an expat Hungarian officer who had represented his country of birth internationally before the war. Even though experienced, the elder officer had only picked up riding again shortly before the selection trials and competed on a former army horse, Reno Overdo, which was actually trained by Borg and started at London 1948 under Lt.-Col. Henry.

Three weeks after team selection the dressage horses were shipped to Europe with only Bob Borg attending them while the other team members flew over to Amsterdam at the beginning of May. Even though the crossing on board of a ship was uneventful, it was a long time for fully trained horses to do nothing. Borg kept the horses supple by flexing them in hand during the journey.

Three weeks after team selection the dressage horses were shipped to Europe with only Bob Borg attending them while the other team members flew over to Amsterdam at the beginning of May. Even though the crossing on board of a ship was uneventful, it was a long time for fully trained horses to do nothing. Borg kept the horses supple by flexing them in hand during the journey.

Unlike today the USET lived on a horribly tight budget and it was out of question to have a dressage trainer with the team to prepare them for their starts at Germany's Olympic trials in Wiesbaden, Düsseldorf and Hamburg. For young inexperienced Haines it was her first time completely on her own far away from home and this proved to be a small disaster, more so as she suffered from pneumonia after coming over to Europe. As a a quality animal and thoroughly schooled by Stecken, The Flying Dutchman did very well at these German shows, placing highly and catching the eye of European experts as did Borg's highly talented Bill Biddle. But the longer Haines and her horse were without their usual tutelage, the more her lack of experience showed negatively.

So what should have become a typical American cinderella story, became an Olympic rider who in less than a year without financial assets and as first American woman at Olympic Games, had no happy end in Helsinki.

Lis Hartel: A Legend in the Making

Completely different preconditions could be found by the first female medal winner at the Olympic dressage competitions, Denmark's Lis Hartel. Aged 30 in 1951 the mother of two had focused on dressage from rather early on, even though her parents had only ridden for fun, but they supported their two horse-mad daughters in every way. At only 22 years of age she had become Danish national champion in dressage and repeated this feat in 1944. But later the same year she contracted polio while being pregnant with her second daughter.

First completely paralyzed, Hartel fought hard to recover. Even though she stayed permanently paralyzed below her knees with also her arms and hands remaining weaker, she began riding again, something extraordinary during those times. With the very calm and reliable mare Jubilee (by Rockwood xx) Lis Hartel even restarted competing successfully from 1947 on, coached by the young Gunnar Andersen, who would later become Denmark's most legendary trainer.

With a secure financial background, a decade of competitive experience, a regular trainer and lots of support from her whole family, Hartel put in an attempt for Helsinki 1952 which was much better than the ones of Marjorie Haines of the USA. And still, Hartel was as insecure in 1951 as the young American. Were she and her mare ready for the challenge a year later?!

It was not only about defending one country's honour back then, but more so doing it as a woman in a male-dominated sport. The pressure to do well must have been considerably higher for all four women who finally appeared in Helsinki's dressage arena in July 1952, beside Haines and Hartel also Norway's Else Christophersen and Germany's Countess von Nagel were qualified.

It was not only about defending one country's honour back then, but more so doing it as a woman in a male-dominated sport. The pressure to do well must have been considerably higher for all four women who finally appeared in Helsinki's dressage arena in July 1952, beside Haines and Hartel also Norway's Else Christophersen and Germany's Countess von Nagel were qualified.

For Lis Hartel the question a year before the Olympic Games was if Jubilee would ever learn to piaffe sufficiently and she posed this question to Colonel Podhajsky, then leader of the SRS in Vienna and Olympic medalist in 1936. Podhajsky and the SRS had been to Copenhagen for a display and on request of Hartel rode Jubilee on this occasion. The Austrian praised the mare's high rideability and great submission. He encouraged Hartel to set Helsinki as her goal as he was convinced Jubilee would have enough time to improve her very rudimentary piaffe.

Podhajsky's judgement turned out to be a bit too optimistic as in May 1952 he received a letter from Hartel saying that she failed on improving Jubilee's piaffe and therefore would give up on her Olympic dream. Podhajsky on the other hand had just judged the possible Olympic teams of Germany, the USA and Chile at the CDI Wiesbaden and had witnessed first hand how imperfect most piaffes had been there, again encouraging Hartel to hold on to her aim representing Denmark in neighboured Finland. It was the decisive advice towards what would become the fairytale of the Helsinki Games and the beginning of a legend that still lives on these days.

Germany: Otto Lörke Again

War defeated Germany was subsequently banned from the first post-war Olympic Games in London 1948, but preparations for its Olympic reappearance started already earlier and more or less practically from scratch. It is without a doubt that no other country world-wide had had such a wealth of high quality dressage trainers, such a wealth of suitable horses for the discipline from their own breeds and such a structured talent scouting programme in the cavalry before the war. However, if one takes a closer look the dressage stable („Schulstall“) of the legendary cavalry school in Hanover did not consist of that many dressage stars, but they came mainly from a few professional dressage trainers who made their mounts available to the cavalry riders who competed at the Olympics on them.

The most dominant of them all had already pre-war was Otto Lörke. Born in 1879, he was responsible for the training of the German emperor's horses before establishing his own successful stable in Berlin after the end of the German Empire. He was appointed to train the dressage stable at Hanover as of 1934. In 1945 Lörke fled with the remaining staffers and horses of the cavalry school, including his successful dressage horses Fanal and Dorffrieden, both Trakehner geldings that had to pull the cart with all his belongings.

He found a refuge in Vornholz, a special place in Westfalia, not far from Warendorf. This little village was home to Count Clemens von Nagel-Dornick whose mote with the same name was a meaningful private stud for thoroughbreds as well as for warmbloods until the 1970s.

There Lörke and his rescued dressage horses not only found a new home, but it was also a source of raw material on four legs which the master would prepare for Helsinki. Soon at his side was his most faithful student Willi Schultheis, who, after some roundabouts after being released as a prisoner of war, found his way to Vornholz to continue working with Lörke.

Even though a few of Germany's foremost riders had survived the war and started competing again, the choice for Olympic level horses was more than small. So Lörke attempted something, which according to Schultheis in Harry Boldt's book „Das Dressurpferd“, only he could succeed in: He trained three horses to Olympic level within less than two years. All three had been bred by his host Count von Nagel-Dornick and two of them, Afrika (by Oxyd) and Adular (by Oxyd), were ready for Grand Prix at age 5. The third, the thoroughbred stallion Chronist xx, was four years older.

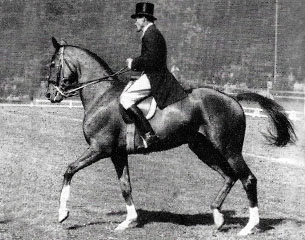

Of these three horses Adular might have been the most talented and suitable for Olympic glory. This strong black Westfalian had been broken in at 3,5-years of age, which was nothing unusual, but his extreme work ethic, his goodwill and ability to learn enabled him to learn the Grand Prix programme rapidly. His good nature and great impulsion caused him to be quite secure in his appearance at a very young age. Even though Lörke and Schultheis rode the horse, an non-professional rider had to be chosen to present him for the Olympics, when the horse was just 7 years of age. It was the 1936 double Olympic champion Heinz Pollay; an ideal choice as his experience and strong abilities brought the best out of the young Westfalian; both won the first Olympic trial at Wiesbaden and again at Düsseldorf.

Of these three horses Adular might have been the most talented and suitable for Olympic glory. This strong black Westfalian had been broken in at 3,5-years of age, which was nothing unusual, but his extreme work ethic, his goodwill and ability to learn enabled him to learn the Grand Prix programme rapidly. His good nature and great impulsion caused him to be quite secure in his appearance at a very young age. Even though Lörke and Schultheis rode the horse, an non-professional rider had to be chosen to present him for the Olympics, when the horse was just 7 years of age. It was the 1936 double Olympic champion Heinz Pollay; an ideal choice as his experience and strong abilities brought the best out of the young Westfalian; both won the first Olympic trial at Wiesbaden and again at Düsseldorf.

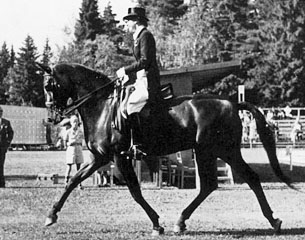

Adular's identically aged half-sister Afrika, another black horse, was less talented, but reached Grand Prix in the same amount of time. Slightly ewe-necked her askew long blaze added to the impression that she was crooked. Additionally she was weak in the kidney region and according to Schultheis „in principle unsuitable to become a dressage horse.“ For him it was only thanks to Lörke that the mare was ready for Helsinki. An ideal lady's ride, the mare was ridden by Countess Ida von Nagel who finished second in the German Olympic trials, even though the mare's piaffe was almost non-existent. Germany's third team horse for Helsinki was Chronist xx, an 11-year-old thoroughbred stallion by Marcellus xx, who had raced in his younger years. Like Afrika he suffered from serious defaults in his conformation for his training.

His apparent weak back made a true connection between hind-legs and forehand a challenge, something which was repeatedly criticised by judges. However he was a charming horse with lots of expression and a good canter tour. As his usual rider Willi Schultheis turned professional, he was not eligible, so Germany's popular jumping rider Fritz Thiedemann was chosen to compete the small stallion in Helsinki where he also jumped with his legendary Holsteiner Meteor.

After their appearances against the Olympic teams of the USA and Chile at the German Olympic trials, Germany's dressage riders had been on the map for Olympic glory once again. But their possible renewal of Olympic success was at a silk thread held by Otto Lörke. Without this man's relentless energy, belief and unique talent Germany wouldn't have had a competitive team for Helsinki.

More on Helsinki in a next article

By Silke Rottermann for Eurodressage

References

DOKR (publisher), Wir reiten für Deutschland, Warendorf 2013, p. 103-105.

Erich Glahn, Reitkunst am Scheideweg, Heidenheim 1956, p. 55 – 61.

Jackie C. Burke, Equal to the Challenge-Pioneering Women of Horse Sports, p. 60-68.

Alois Podhajsky, Ein Leben für die Lipizzaner, München 1960, p. 325 / 326.

Franz-Rudolf Bissinger (publisher), Sankt Georg Almanach 1952, Neuss am Rhein 1952, p. 20-73; 191 – 201.

Willi Schultheis, „Start bei Null“, in: St. Georg 7 / 1995, p. 70 – 72.

Clemens von Nagel, Otto Lörke, in: Sankt Georg Almanach 1966, Düsseldorf 1966, p. 23-30.

Harry Boldt, Das Dressurpferd, Lage-Lippe 1978, p. 74 / 75, 83.

http://www.chronofhorse.com/article/chronicle-over-decades-1950s

Untacked, Summer 2014 edition, page 40 – 42.

http://library.la84.org/6oic/OfficialReports/1952/OR1952.pdf