-- by Silke Rottermann for Eurodressage

This is a first of a five-part series on the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the perfect introduction to the Games happening this week

Japan’s capital of Tokyo has a long connection with the Olympic Games, although ill fate not only befell it in 2020 when the corona pandemic forced the postponement. Already in 1940 the outbreak of the second Japanese-Chinese War prevented Tokyo to hold the Games for the first time. Finally, 24 years later, the Olympics were opened on 10 October 1964 and the Olympic fire was highly symbolically lit by Yoshinori Sakai, who was born exactly on 6 August 1945 when the first atomic bomb hit Hiroshima.

The allocation of the 1964 Olympic Games to Asia meant for the equestrian world that the majority of horses and riders had to tackle a long and, for some, pretty adventurous journey.

Whereas Tokyo 2021 is the usual meticulously planned expedition, executed by highly specialized equine travel agencies like we know them for a longer time now, the equine journeys to the first Olympic Games in Tokyo 1964 saw horses on a ship caught in a heavy typhoon, horses being put down on the airplane, horses suffering heavy turbulence, a smoking propeller engine and unforeseen landings.

Back then it seemed all, but a certainty that the four-legged athletes would arrive safe and sound on Japanese soil. The Olympic future of dressage was neither a certainty. Scandalous judging at the Games of Stockholm eight years earlier had put the discipline into the crossfire of the IOC with its president Avery Brundage.

From Rome 1960 to Tokyo 1964: The Stockholm 1956 Aftermath

At the beautifully located Olympic equestrian Games of 1956, set in the honorable Olympic stadium of Stockholm 1912, a judging scandal took place and overshadowed dressage which saw a record breaking 36 participants from a growing number of countries.

Two judges had put their fellow countrymen’s rides on all medal places. Although nationalistic judging was not a new appearance at the Olympic Games, the credibility of a whole discipline, part of the Olympic program since 1912, seemed in severe danger. The more so because during the opening ceremony of Stockholm, for the first time in history the judges had sworn an oath to reassure fair and impartial judging.

flight to Tokyo

The new measures all served one goal: to ensure nationalistic judging was eliminated and to secure the Olympic future of the discipline.

In Rome these „safety measures“ were added another new introduction to the judging system: Each test of the ride-off was filmed and analyzed by the judges before marks were officially announced. What was thought as another measure against bad judging, had at the same time negative consequences because it took three days until the final results were announced and this in turn not only killed the interest of the spectators, but on some certainly left the impression that dressage was a kind of secret science.

For Tokyo similar measures were planned.

Tokyo 1964: Pre-Olympic Trouble

Before the Olympic Games in Tokyo 1964 and after repeated requests by the FEI, the IOC finally agreed on reinstalling the team competition in dressage, but made it obligatory that it would only take place if at least six teams started. What sounds a pure formality in our days, became a real problem prior to the Olympic Games in Tokyo. The struggle to have the team competition back wasn’t over with the IOC’s permission to have one.

At that time (like again in Tokyo 2021) a team consisted of three riders. However countries which could field three Grand Prix riders and also had the financial assets to ship them all around the globe to Asia, appeared dangerously scarce.

In the same year in Germany the idea came up to hold the Olympic equestrian competitions at Aachen instead of Tokyo, in order to downsize transporting costs and because of the lack of experience the Japanese were thought to have with organizing equestrian events on that scale. In the end that idea was never seriously discussed. The IOC on the other side took a clear stand by saying that either it would be ridden in Tokyo or not at all.

Luckily Japan was able to provide their first ever dressage team at Olympics and the USA finally decided to take part with their all-female team on very experienced horses after Dr. Reiner Klimke had flown to Gladstone in late summer to encourage them to send a team. However, it depended on Europe, then still the undisputed heart of the discipline, to make a team competition possible. While Germany, Switzerland and the Soviet Union - at that time the leading three nations in dressage - agreed to send teams, it began to look bleak when Romania withdrew its entry and France decided that sending one was too expensive. Great Britain, Canada and Argentina sent individual riders only.

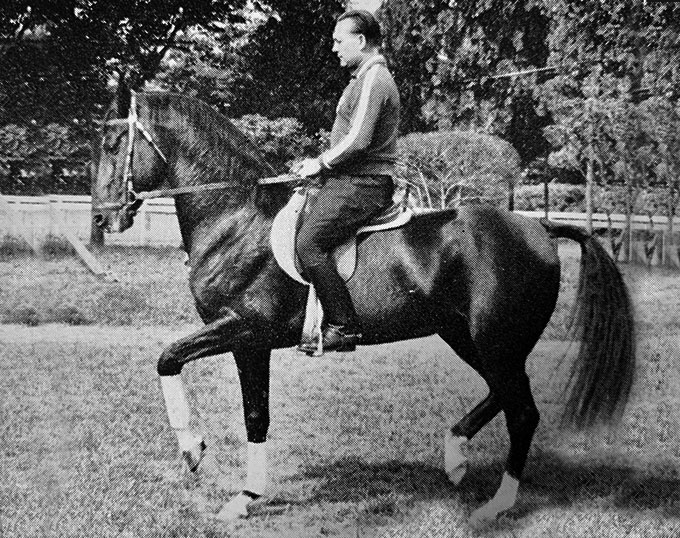

Finally the German doyen Josef Neckermann (1912-1992), one of the favourites with his drop dead gorgeous Holsteiner mare Antoinette, invited the Swedish team to fly to Japan to make sure a team competition would take place. It continued to be on the knife edge when Sweden’s quadruple Olympic champion Henri St. Cyr (1902-1979), a certainty for his team, suffered a severe car crash in Paris and as a consequence could definitely not take part in his 6th Games.

Even though being a traditional dressage country with a renowned Swedish warmblood breeding programme, Sweden at that time, like most of the countries, could not dig too deeply into a reserve. Gaspari, the magnificent chestnut stallion who should later become a legend in breeding and had already competed for Sweden at the 1960 Olympic Games with his trainer Yngve Viebke, was sent to Paris to be prepared for Tokyo by St. Cyr. After St.Cyr’s accident the stallion was hastily re-routed to be matched with Hans Wikne (1914-1996) as a new combination for Tokyo.

As a matter of fact the first team competition in dressage since 1956 only became a reality when all horses of the six teams arrived in Tokyo safe and sound and could be started. Never before or after a team competition had been at such risk until the last minute. The troublesome journeys of several teams to Tokyo underlines why.

Typhoon and Turbulence: The Adventurous Journeys to Tokyo 1964

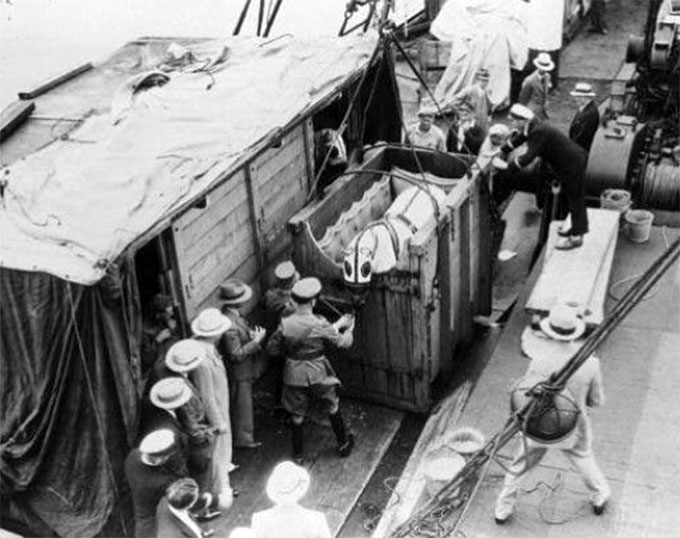

While transporting horses for competitions overseas by ship had been the norm well into the 1950s, in 1954 the Germans flew their best jumping horses for the first time in propeller machines to the USA for a show tour there. The USET in turn first flew their horses to the Olympic Games in 1956. However flying horses remained not only a cost intensive, but also a comparatively risky affair well into the 1960s. The big specialized agencies dealing with professional horse transport did not exist back then like we know them today; the flying stalls were usually timbered just for the purpose and had not only been quite flimsy compared to he containers used today, but also comparatively narrow. This in turn hold the real danger of horses getting claustrophobic and panic during flights.

While the few European countries, which could afford taking part in the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles (USA)n still sent their horses there by ship and train, the journey to Japan was tackled by almost all Europeans with chartered airplanes. Australia and New Zealand, non-starters in dressage, still relied on ship transport for their jumpers and eventers.

The Soviet dressage horses, among them the title defender Absent of Sergej Filatov and the future Olympic champion of 1968 and 1972, Ikhor of Ivan Kizimov, approached Japan by ship and their journey did not only last 14 days, but the horses experienced a nightmarish sea crossing due to a typhoon called „Wilda“ and understandably arrived at their destination not in the best condition, but recovered in time for the competition.

Planes started among other cities from Fiumicino (Rome), Schiphol (Amsterdam), Zurich-Kloten, Orly (Paris), London (GBR), and Newark (USA), but at different dates. Some only flew in fairly shortly before the competition started, while others planned weeks of acclimatisation and already arrived at the end of September 1964. Many nations still relied on propeller machines which had less range than the modern jet planes, but with which there was more experience existing regarding flying horses.

Germany’s dressage contingent of Dux and Arcadius of Dr. Reiner Klimke (1936-1999), Antoinette and Asbach of Josef Neckermann and Remus of Harry Boldt (*1930) faced a well planned and quite trouble-free journey compared to some of their equine colleagues from other countries. The journey of the Germans started during the night from the 27 to 28 September 1964 by trailering the horses from the bases in Frankfurt, Iserlohn and Münster to the Dutch airport of Schiphol in Amsterdam. A DC-8 called „Alfred Nobel“, provided by the Dutch KLM company, had flown in from New York for this purpose and the traveling boxes for the horses had first to installed once upon arrival at Schiphol.

Germany had planned a generous time of acclimatisation for their horses when their flight to Japan started at 12 o’clock on 28 September, a good three weeks before the Grand Prix would take place. They had planned to take a modern jet plane and the so-called „polar route“ with just one stop at Anchorage to refuel. While their departure in Schiphol was a bit delayed because a damage was discovered on the way to the runway and had to be repaired, the flight itself passed comparatively well. The horses safely landed on 29 September 1964 at 3 pm after 27 hours traveling time.

While the horses on board traveled generally well and arrived at Haneda airport in Tokyo in good state, Reiner Klimke’s Hanoverian gelding Dux had sprained his tail root which healed enough before the competition started (more about this in a next article with the memories of Grete Kemper, his groom).

Unlike the German team, their most serious rivals for the gold medals, the Swiss, left home soil a bit closer to the start of the competitions. Like for most horses, it was also the first flight for the 4 of the Swiss team. Double European champion Henri Chammartin (1918-2011) took his star Wolfdietrich and the feisty Woermann as the reserve, his fellow Gustav Fischer (1915-1990) his 1960 silver medalist Wald und young Marianne Gossweiler (*1943), the first Swiss woman on a summer Olympic team at all, had her grey Stephan.

While the British equestrian team left no stone unturned in preparation of their horses’ flight and did a short trial flight with them before Tokyo after which they enlarged the stall of one of the horses, such safety measures neither took place in Switzerland nor is it known that it happened in the other countries.

Prior to the flight of the Swiss, the stalls which would be used on the plane had been delivered to the Swiss cavalry school in Berne where the horses could get acquainted with it. It would stead them well because their flight turned out to be the longest of all horses who competed in Japan. It departed on 7 October 1964 in Zurich-Kloten in a DC-6, a propeller plane and had five regularly scheduled stop-overs to refuel and check the plane, each planned to take 60-90 minutes.

Just before one of these planned stop-overs, in Rangoon on 8 October at 3 in the morning, Swiss multiple Olympic jumping rider Paul Weier (*1934) told Eurodressage that the plane struggled with a balked landing, but hit the ground running at the very last second because the airport lights malfunctioned. The plane had to circle some time over the airport until the airstrip got illuminated by electricity and oil lamps again. The second attempt was a very hard landing. When the pilots checked-over, one of the four propeller engines started to burn. They reacted quickly by fully turning on the propellers which caused so much wind that the flames got extinguished. But the plane then had to be repaired for over 7 hours during which neither rider nor horses were allowed to leave the plane. According to Weier who was traveling with his horse Satan on the plane, the outside temperatures rose to 40 degrees Celsius and no air conditioning was available for the horses on board.

Not surprisingly, most of the horses had a fever after the ordeal and so they were not allowed to move in their foreseen boxes at the Equestrian Park, but instead got separated in quarantine stables. There they had spent three days to make sure they did not suffer from an infectious illness. Finally they were allowed to move to the actual location, but for safety reasons got isolated three more days before being released on 16 October, just six days before the start of the dressage competition.

Whereas the Swiss had the longest journey, the most dramatic one was probably experienced by the US equestrian team, though none of their elder dressage horses were concerned. They were experienced air travelers. A propeller plane was hired to fly the horse contingent of the USET from Newark airport to Tokyo. The US team vet at that time, the late Dr. Joseph O’Dea (1921-2006), reported in his fascinating read „Olympic Vet“ that shortly after the take-off a thunderstorm caused strong and ever increasing turbulences. While most of the horses seemed unperturbed, the experienced thoroughbred Markham, the 1960 Olympic horse of eventing legend Michael J. Plumb, began to romp increasingly, suffering from a kind of what Dr. O’Dea called a "van fit." Despite all thinkable measures, the horse did not calm down and finally got his front-legs over the door of his box, beginning to damage the ceiling plates over his head. The danger of a horse becoming unsettled, climbing his stall and damaging the plane was present with every flight at that time, but unfortunately became very real for the US team on the way to Tokyo. The unavoidable had to be done when the flight engineer asked for action and Markham was put down and very probably this saved the other animals and humans on the plane.

Markham’s tragic death forced the plane to land in Chicago where the dead body was unloaded. The trouble was not yet over for the US team on board as the plane repeatedly had to fight against heavy turbulences and head winds, before finally reaching Tokyo airport safe and sound.

Preparing for Olympic dressage in „Baji Koen“

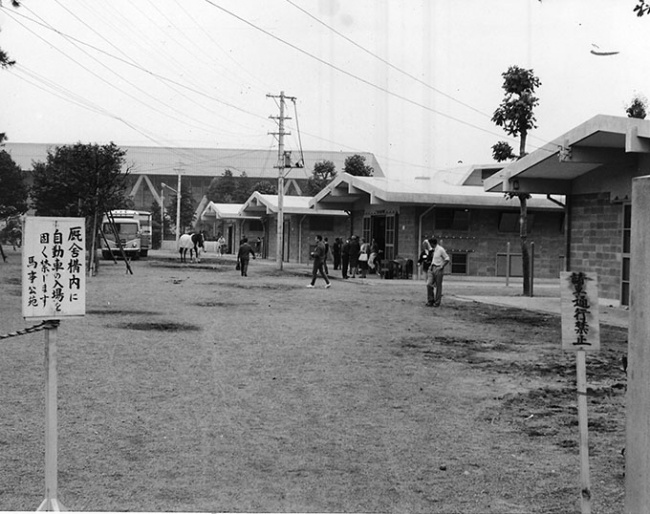

Once the far traveled and tired horses arrived at Haneda airport, they were immediately welcomed by trucks which brought them straight on to Tokyo’s Equestrian Park "Baji Koen," located not far away. And it is exactly the place where the 2021 Olympic horses have moved in this year. One special fact about the upcoming 2021 Games is that about 50% of the sport facilities are already existing and located in the so called „Heritage Zone“. Baji Koen in Setayaga, which belongs to the Japan Racing Association, is one of these.

Olympics. They had to compete in a thunderstorm

followed by fog and rain

In the end the organizers stuck to their grass stadium with tribunes on three sides, even though the weather happened to be rather bad!

The horses were stabled in one of 4 stable sections which were very airy and spacious and housed 160 horses at whole.

The facility was more than up to date for its time with paddocks for the horses, a race-track, an equine clinic, an isolation stable, a forge and even its own police-station back then.

In 2021 the horses return to „Baji Koen“, in the same place, but of course the facility is now updated to 21st century standards, with air-conditioned stalls and indoor arena with all the modern amenities thinkable.

Even though there were only 22 starters in Tokyo 1964, it can be said that the best were there to ride for the medals. While it was pretty much sure that the Germans, the Swiss and Soviets would ride for the team medals, the individual competition seemed surprisingly open. The day form would be decisive, but names like Chammartin, Fischer, Neckermann, Klimke and Filatov were the first to be heard when possible medals were concerned.

Continue reading: Part II: Interview with Paul Weier on flying 1964

-- by Silke Rottermann © Eurodressage - Photos © St. Georg / Paul Weier - No Reproduction allowed without written consent

References

Internet

- Baji Koen Equestrian Park

- Tokyo 2020 Equestrian Park

- hTokyo 2020 Returns at 1964 Equestrian Park

- Equestrian Sport Explanatory Guide

- Three Girls for the Grand Prix

- Dressage Master Christilot Boylen Embraces the Journey

- FEI History: 1956 Melbourne Olympics

- FEI History: 1960 Rome Olympics

- FEI Hitory: 1964 Tokyo Olympics

- Golden Oldies: Josef Neckermann's Antoinette

- Golden Oldies: Remus: From Exchange Object to Serial Medallist

- Golden Oldies: Stephan: Field Accident Gone Olympic

- Golden Oldies: Bonheur xx: From the Race Track to the Olympic Dressage Arena

- hGolden Oldies: Woermann: a Rascal on the Olympic Throne

- http://www.olympedia.org/athletes/23434

- Olympic Horse is Destroyed After Going Berserk on the Plane

- Olympic Games 1964

- Jim Wofford had Quite an Olympic Ride

Books

- Helmut Wagner, Kavalkade Band 11, Olympische Reiterspiele 1964, Mönchengladbach 1965, pages 13-25 and pages 85-117.

- Verlag ST.GEORG, St. Georg Almanach 1964, Düsseldorf 1964, pages 26 -38.

- Josef Neckermann, Im starken Trab, Warendorf 1992, pages 80 - 81 and pages 124-133.

- Joseph C. O’Dea, Olympic Vet, Genese NY 1996, pages 81-103.

- DOKR, Wir reiten für Deutschland, Warendorf 2013, pages 136-141.

- SVPS / Max E. Ammann, 120 Jahre Pferdesport Schweiz, Bern 2020, page 313.

- Alois Podhajsky, Reiten&Richten-Erfahrungen und Vorschläge, München 1974, pages 95 and 96, pages 100 and 101.

Magazines

- Marianne Gossweiler, Tokio war ein wunderschönes, unvergessliches Erlebnis, in: Schweizer Kavallerist 1964, p. 27-32.

- Horst Niemack, Der Grand Prix brachte uns olympisches Silber und Gold, in: St. Georg 1964.

Interviews

- Grete Kemper (née Klimke) in August 2019.

- Marianne Fankhauser (née Gossweiler) in November 2020.

- Paul Weier in December 2020