by Silke Rottermann for Eurodressage

This article is a continuation of 1964 Tokyo Olympics series

Part I: Team Competition in Jeopardy and Dangerous Travels to Tokyo by Air and Sea

Part II: Paul Weier on Pioneering Horse Transport to Tokyo, by Air,

Part III: Grete Kemper, Groom of Reiner Klimke's Dux, Remembers Tokyo.

Part IV: "Joy, Fair Spark of the Gods" in Far Away Japan

It was not an easy way, neither for the six teams, nor the four individual riders to qualify for the 1964 Olympics in Japan, nor was it to get there and compete in late October of that year.

Own Story to Tell

Each horse and rider had their very own story to tell which began long before they entered the planes and ships that would bring them to Tokyo.

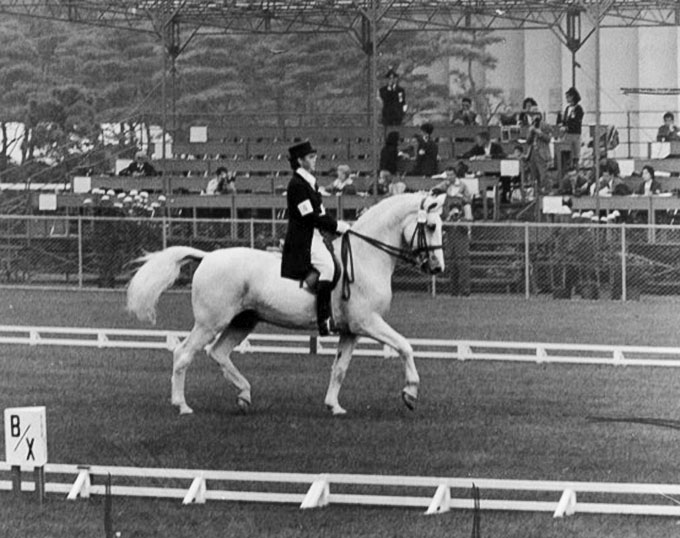

There was Christilot Hanson, nowadays a legend in her own right, setting a special record at her first Olympic Games at the age of 17, riding her OTTB Bonheur xx. There was Swedish multiple Olympic fencing medalist Bengt Ljunqvist debuting in the discipline of dressage at which he was just equal a genius as he was in his first sport, even though with no luck in Tokyo. There was 21-year-young Swiss Marianne Gossweiler who became the first Swiss woman to compete in the Summer Olympics. And of course it was the Olympic dressage debut of somebody who was to become the epitome of this discipline: Dr. Reiner Klimke. Four years earlier he had competed in eventing at the Rome Olympics.

The 22 horses in the Grand Prix represented very different types and breeds: For example the narrow OTTB Bonheur stood in stark contrast to the typical square Lipizzaner stallion Conversano Caprice, or the peculiar looking Akal Teke Absent. Then there was the highly refined Holsteiner mare Antoinette who contrasted with the pretty, but strong boned Swedish breeding stallion Gaspari.

The horse types differed and so did the training. German chef d’equipe, General Niemack, explained in St. Georg magazine that "Only horses which are submissive and able to go forward with impulsion and carry themselves with a light contact will be able to succeed."

The Judging Panel

Three honourable gentlemen had to decide about success and failure and they had all one thing in common: They had represented their country at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. Gustaf Nyblaeus (1907-1988) from Sweden and Georges Margot (1902-1998) from France had competed in eventing, while Frantisek Jandl (1905-1984) from Czechoslovakia had been on his country’s dressage team 28 years earlier.

The three judges were all positioned at a short side in single huts and each judge awarded his own marks to the 32 movements shown during the Grand Prix. However, the collective marks were awarded by the judges together.

The Grand Prix did not determine the team nor the individual medals, like in Stockholm 1956 and the earlier Olympic Games. Instead it served as a pure team competition of which the result decided who would be allowed to move on to start in the ride-off the next day. Scores from the Grand Prix and ride-off counted together decided the individual medals and placings.

12.5 minute Grand Prix

In 1964 the Grand Prix was 12,5 minutes long and there was still a time limit given which required a certain sense of tempo from the riders. Anybody who exceeded it got penalty points (1/2 deduction per second over).

In Tokyo, unlike in Rome four years earlier, the end result of each ride was announced pretty immediately afterwards, but not the points awarded by the single judges. This had already occasionally been criticized between the Wars and also in Tokyo critical voices became loud that this practice wasn’t helping the discipline.

"Riders and the spectators have a right to get to know how a judge saw the rides. Otherwise the judge remains in his anonymity and judging appears as secrecy," General Niemack remarked on Tokyo in St. Georg magazine.

However, the performance of the judges in Tokyo had been widely acknowledged by experts from different countries. Alois Podhajsky, himself an Olympic dressage medalist, international judge and legendary leader of the SRS in Vienna, remarked in his book „Riding&Judging“ that "in Tokyo only one of the judges (Nyblaeus) had to judge his own compatriots. He was unbiased (…). The correctness of this judge’s opinion was confirmed by the other two members of the jury."

School Children to Fill the Seats

There were not too many spectators in Tokyo who discussed the results because there was comparatively little interest in a discipline the Japanese were more or less strangers to. Spectators travelling for the Olympics, like it is the norm nowadays, was pretty unknown then.

The organizers ultimately would bring school children to fill the oversized tribunes, something which was also repeated 22 years later in Seoul when the Olympics returned to Asia (and even at the 2010 World Equestrian Games in Kentucky).

Little did one know then that 57 years later horses and riders would return to Tokyo to compete for Olympic glory in a ghost stadium with no spectators at all…

The Team Competition on 22 October 1964

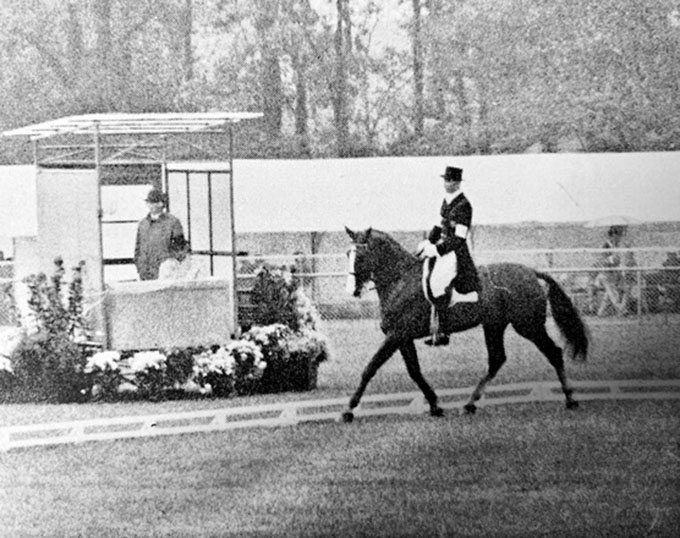

The Grand Prix, which kicked off in the morning of 22 October 1964, suffered increasingly from bad weather and back then it was common to perform on grass. A few horses were more unhappy though with the numerous umbrellas in the stands and the huge plastic sheets which were hastily pulled over the cameras around the arena, than with the grassy surface.

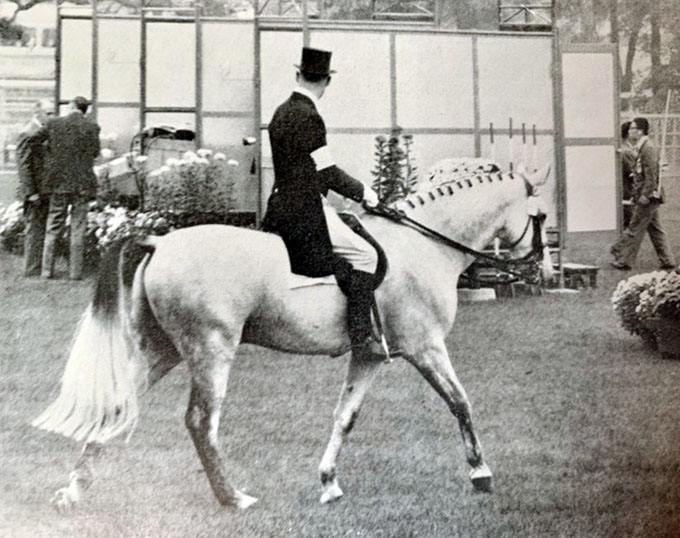

The Swiss were definitely on the Germans’ heels, even though they had suffered a serious setback just before the Grand Prix started. Henri Chammartin’s magnificent Swedish gelding Wolfdietrich (by Daladier xx), on whom he had become European champion the year before, went lame and he had to fall back on the less reliable Woermann (by Dianthus), a horse who could easily confuse genius with insanity. On that particular day in October 1964 the dark brown Swedish gelding seemed to be aware of the responsibility he carried and showed a polished ride which brought him to second place of the Grand Prix. The ease and the freedom with which the Dianthus-son moved and the finesse with which the outstandingly sitting Chammartin presented the horse, left the biggest impression on the French Georges Margot, who placed them first.

With Chammartin’s excellent result in the back, Rome silver medalist Gustav Fischer, like Chammartin a representative of the Swiss Cavalry School in Berne, managed to show one of his best Grand Prix. Wald, his tall and big framed Swedish gelding (by Drabant), showed several highlights, over all his big striding half-passes, pirouettes and the big floaty passage. He placed just ahead of Filatov.

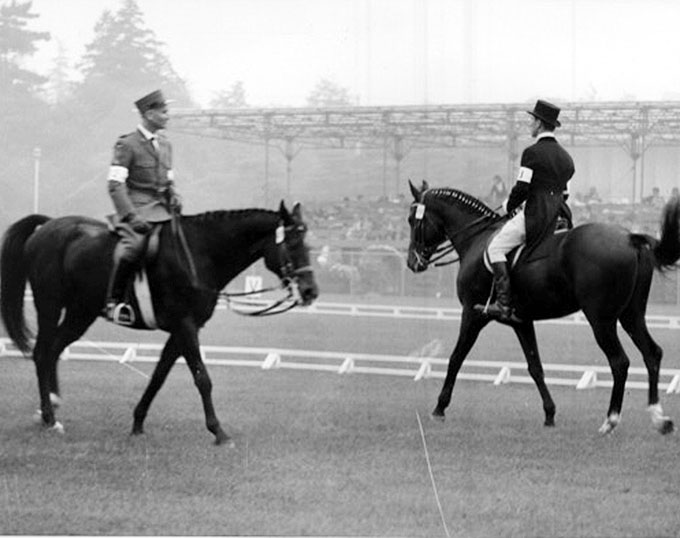

The 34-year-old Harry Boldt from the German team totally unexpectedly exceeded the expectations as one of the early starters. On the rather small Westfalian gelding Remus (by Ramzes x) the Iserlohn based rider had the ride of his life. Not only Gustaf Nyblaeus from Sweden placed him first, but his overall result saw him at the head of the field after the Grand Prix.

The Team Medalists

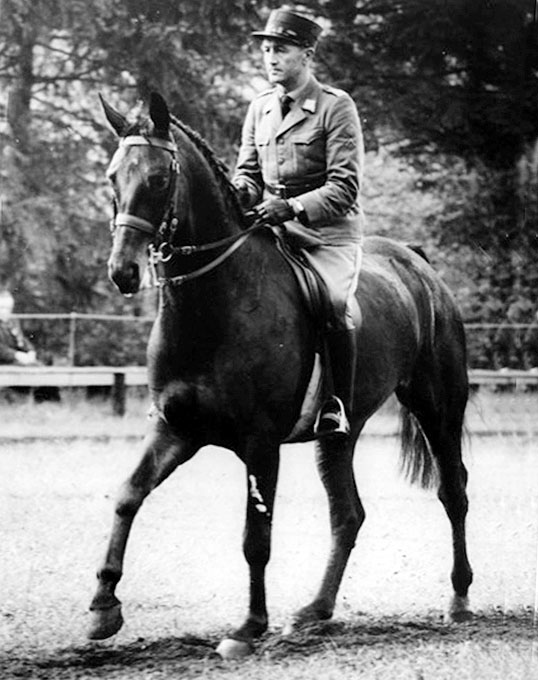

The Soviet Union won bronze, mainly thanks to the outstanding performance of Absent and Filatov. Ikhor, this Ukraine bred gelding, placed a respectable 10th at just 6 years of age (!). His time would come four years later when he became individual Olympic champion with his rider Ivan Kizimov. The Soviet team’s third rider, Ivan Kalita on Moar, ended in 15th place. Remarkably it would be Kalita to ride the legendary Absent to team silver four years later in Mexico-City, the famous horse’s 3rd Olympic Games.

The Tokyo Olympic stallions not only proved themselves in the show ring but later on also in breeding. Just like Sweden’s Gaspari, Absent continued with a second career in breeding. While Gaspari’s son and lookalike Piaff won team gold 1968 and individual gold in 1972 with Liselott Linsenhoff, Absent’s son Abakan (Ridden by 1970 Worlchampion Elena Petushkova) sadly died shortly before the 1980 Olympics in Moscow and could not entirely walk in his father’s footsteps.

Sweden in fifth place had began well with a 9th and 11th place, but the off-day of Karat, the 1964 Swedish dressage champion after all, who could not be calmed down and finished last on that day, dashed all hopes for a possible team medal. He would continue his Olympic career with British rider Domini Morgan (Lawrence) in 1968 and 1972 with improved results.

Of the four individual riders the Dutch born British rider Joan Hall, later a very well respected O-judge, placed best. With her charming purebred Lipizzan stallion Conversano Caprice, whom she competed in Rome 1960 and would again show in Mexico-City 1968, she finished in 12th position. Just ahead of the Argentinian Francisco Obdulio d’Alessandri (*1930) with the beautiful Argentine bred Vidriero, a horse that had won a Pan American silver medal a year earlier behind Rath Patrick xx.

Writing Olympic History

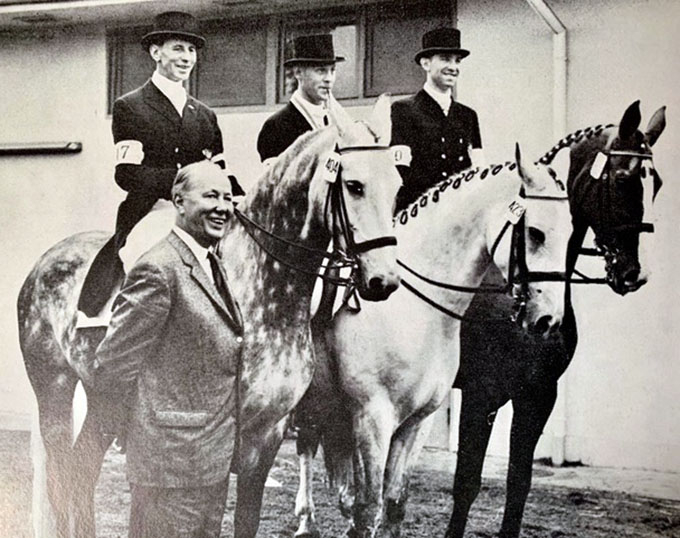

Niemack with Neckermann, Boldt and Klimke

The then German national anthem - "Joy, fair spark of the gods" - rang out for the victorious German team, the masterpiece of Ludwig van Beethoven which now serves as the hymn of Europe. In 1964 it was chosen to be the hymn being played for the last all German team at Olympic Games until Barcelona 1992.

There was only one medal per team awarded by the organizing committee and the Germans were quick handing it to to their best man on that day, Harry Boldt and the same did the Soviets. The Swiss gentlemen, on the other hand, gave their medal to Marianne Gossweiler, now not only the first female Swiss athlete at Summer Olympics, but also their first ever female medal winner!

The Ride-Off: The Closest Ever Olympic Result in Dressage

For the first time in Olympic history the six best riders of the Grand Prix were now faced with the situation to confirm, if not improve their results in a specially designed ride-off with 23 movements and an allowed time frame of 6:30 minutes to execute them.

Jandl, president of the jury, remarked in the book „Kavalkade“ that "film control is a good thing, but only if it is not executed under time pressure. It is only useful if the judges have their score sheets with them to enable corrections. This wasn’t the case in Tokyo."

The fact that there was no clear favourite or outstanding pair in Tokyo made it even more difficult for the judges to assess the rides and it became a thriller indeed. In the end the first four placed horses were only 19 points apart.

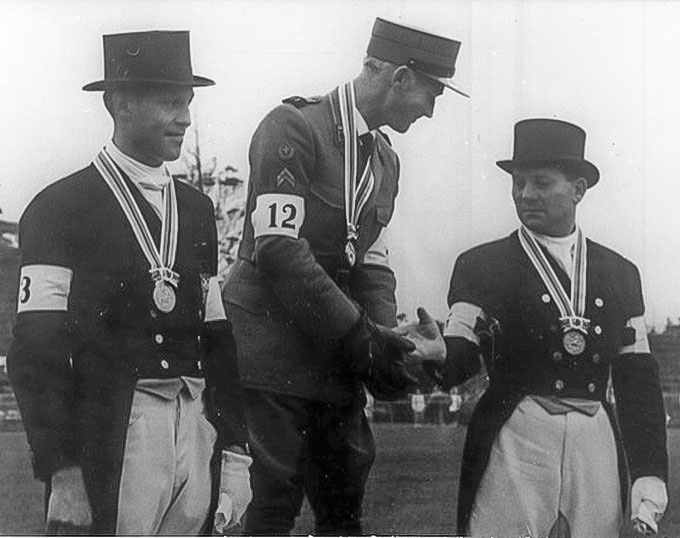

Individual Gold for Chammartin

He became Olympic champion with the most points and with the tiniest possible lead at that time, but without having won either of the two classes that counted—something unique in Olympic history.

For Harry Boldt the loss of a close and yet so far gold medal left him with mixed feelings. He could not know then that his best horse ever, Woyzeck, was still to come, but with him he would again loose individual gold to a Swiss rider, twelve years later in Montréal-Bromont.

Identically tight was the run for the bronze medal. Sergej Filatov won the ride-off itself of which the focus was on the strong sides of his stallion Absent, the piaffe and passage. This enabled him to obtain the individual bronze medal with one little point ahead of Gustav Fischer and Wald who were the unlucky fourth.

General Niemack drew his conclusions after the Olympic Games came to a close, which he expressed in St. Georg magazine: "The judges had managed to clearly detect the top group and placed it accordingly. A really outstanding, radiant winner was lacking. None of the six riders in the ride-off showed a really glamorous performance. This is probably the reason for the differing opinions of the judges who was the winner."

Olympic Conclusion of 1964

One of the judges at Tokyo, Frantisek Jandl, mentioned in „Kavalkade“ that the level shown in Tokyo had been praiseworthy on average. According to him only a few horses placing at the bottom of the field had shown that they were not really ready yet for the Grand Prix.

About the performance of the jury to which be belonged to he said: „As the president of the jury in Tokyo I want to stress that all judges had been totally independent in their judgment, also during the film presentations during which they did not change one single mark. The result of Tokyo is to be considered as a community work of independent judges. They were not always the same opinion regarding details, but this cannot be differently if we have such equal top performances like in Tokyo.“

-- by Silke Rottermann © Eurodressage

Photos © St. Georg / FEI History Hub - Archive Schweizer Kavallerist / Thomas Frei - No Reproduction allowed without written consent

Related Links

Part I: Team Competition in Jeopardy and Dangerous Travels to Tokyo by Air and Sea

Part II: Paul Weier on Pioneering Horse Transport to Tokyo, by Air,

Part III: Grete Kemper, Groom of Reiner Klimke's Dux, Remembers Tokyo.