Jean-Philippe Giacomini has contributed an insightful, detailed three-part series on the piaffe and passage by fashion, history and genetics. Piaffe and passage are the two movements that put "Art" in Equestrian Art and epitomize the successful training of the high performance dressage horse. Read all about these two stunning dressage movements in this series.

The Historical Roots of the High School Movements

Piaffe and passage are the two movements that put Art in Equestrian Art and epitomize the successful training of the High School horse. In French they are called “airs,” for which the closest English translation is a “look,” an “attitude,” a “tune,” all words that express the allure of piaffe and passage and their cadence. In relation to horsemanship, “air” means a gait or an exercise and is the stylization of the fleeting natural displays frequently performed by groups of excited stallions playing at liberty, particularly Iberians. Such mock fights also result in the rears that anticipate levade, the kneeling-down that precede the reverence (equine bow) and the jambettes (lift and extension of the front legs) that inspired the Spanish (or suspended) walk.

The dressage-style form of these movements has become the archetype of the Riding Horse presented in all its glory. To this day, piaffe and passage are the cornerstones of the three Olympic Dressage tests (Grand Prix, Grand Prix Special, and Grand Prix Freestyle) and they are attributed a considerable proportion of the total marks. They are clearly the hardest movements to train correctly and many performers fall short of the mark. Levade and the other airs- above-the-ground (ballotade, cabriole and courbette) are the mainstay of the classical schools of the Baroque tradition (Vienna, Lisbon, and Jerez) while the Spanish walk and Spanish trot, the crowd favorites, are seen in the exhibition programs of baroque horses the world over.

The dressage-style form of these movements has become the archetype of the Riding Horse presented in all its glory. To this day, piaffe and passage are the cornerstones of the three Olympic Dressage tests (Grand Prix, Grand Prix Special, and Grand Prix Freestyle) and they are attributed a considerable proportion of the total marks. They are clearly the hardest movements to train correctly and many performers fall short of the mark. Levade and the other airs- above-the-ground (ballotade, cabriole and courbette) are the mainstay of the classical schools of the Baroque tradition (Vienna, Lisbon, and Jerez) while the Spanish walk and Spanish trot, the crowd favorites, are seen in the exhibition programs of baroque horses the world over.

TWO PERFECTLY NATURAL MOVEMENTS BECOME STYLIZED BY DRESSAGE

Since the beginning of time, horses, particularly the hot-blooded breeds, have piaffed in some way from impatience when kept away from company or passaged in displays of sexual excitement. Horsemen enjoyed the spectacle of these contained, yet intense, displays. Along the centuries, they discovered clever ways to entice their horses into some kind of prancing on command. Their motives ranged from the sheer pleasure of the experience to attract the eye of the ladies, challenge the aggression of enemies, or elicit the respect of their comrades on a day of victory.

Horses who offer this kind of movement naturally have always been sought after. This is probably why most cavalry officers preferred to ride stallions, even in civilizations that knew the benefits of gelding. A frequently repeated myth is that piaffe is a naturally aggressive behavior related to the anticipation of fighting between two stallions. In reality, horses provoking each other or facing a bull in the arena, hardly ever piaffe instinctively. The natural tendency is to lower themselves and keep their feet close to the ground in preparation for moving quickly in the direction the fight may take them (like cutting horses). Most horses resisting the demands of their riders will brace their feet in this attiude of preparation for afight. As a result, performing calmly a cadenced, elevated piaffe or passage under saddle is the mark of impulsion and utmost control, and the opposite of natural equine aggression or simple resistance to our demands (as long as we can also stop it).

Horses who offer this kind of movement naturally have always been sought after. This is probably why most cavalry officers preferred to ride stallions, even in civilizations that knew the benefits of gelding. A frequently repeated myth is that piaffe is a naturally aggressive behavior related to the anticipation of fighting between two stallions. In reality, horses provoking each other or facing a bull in the arena, hardly ever piaffe instinctively. The natural tendency is to lower themselves and keep their feet close to the ground in preparation for moving quickly in the direction the fight may take them (like cutting horses). Most horses resisting the demands of their riders will brace their feet in this attiude of preparation for afight. As a result, performing calmly a cadenced, elevated piaffe or passage under saddle is the mark of impulsion and utmost control, and the opposite of natural equine aggression or simple resistance to our demands (as long as we can also stop it).

The universal standard for piaffe and passage has been set by the Baroque breeds of Iberian origin in the same way that trot extensions and one-tempi changes are the clear hallmark of the genetic ability of modern Warmbloods. More than any other equestrian population, Iberian riders have enjoyed the admiration created by their riding skills combined with the talent of their horses for collection and agility. The history of Spain and Portugal is part and parcel of the development of horsemanship. The ancestral riding ability of Celt-Iberian warrior chieftains assured their superiority in combat, secured their political power at home, and provoked the admiration of conquered people in their victory parades. The Celt-Iberians are reputed to have invented the side-reins to obtain some collection (probably around the fifth century B.C.), and maybe the precursor of the stirrup (a sort of surcingle under which they could slip their feet or their knees). These warrior-horsemen famously defeated the Greek Cavalry commanded by Xenophon when Sparta hired them as mercenaries during the Peloponnesian Wars against Athens. Later, Xenophon acknowledged in his memoirs that the unique fighting technique of these warriors, apparently based on the athleticism and obedience of their horses, was superior to the Greek approach to mounted combat. In other historical periods, Iberians loaned their cavalry to Hannibal who defeated Rome, resisted the Moor invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in the 8th century, and taught bullfighting to the Islamic occupant of Andalucia. Dom Duarte of Portugal wrote probably the first European riding book in 1345, mixing his equestrian knowledge with moral and political advice. It is obvious to anyone who has visited a country fair in Spain or Portugal or witnessed a “cavalcade” in Central America that a large proportion of local riders can perform piaffe and passage at the drop of a hat with varying degrees of proficiency but always with great enthusiasm. I remember that, on a road trip in Costa Rica, I saw a young boy, at a crossroad riding a skinny gray mare bareback with a rusty bit and a string bridle. He performed a magnificent piaffe, slow and elevated, while waiting for the cars to go by.

THE BEGINNINGS OF PIAFFE AND PASSAGE AS FORMAL EXERCISES

The transformation of piaffe and passage from the expression of joint equine and human exuberance to formal exercises of horsemanship came about as the unexpected consequences of an accident of history. In the sixteenth century, King Fernando of Aragon sent troops to protect the Kingdom of Naples (which he owned) from French invaders, where his light cavalry defeated the heavy horses of the French knights. These troops stayed in Naples and imported into Italian life the small Spanish horse known as a “Jennet”, along with other national customs, such as bullfighting, which became all the rage in Italy. Amazed by the talent and willingness of Spanish horses, Italian horse masters of the Renaissance, including Federico Grisone, his student Count Fiaschi, and later Pignatelli, slowly devised the first crude training systems aimed at reproducing on demand the naturally collected and brilliant movements of the smaller Jennets that their own heavier mounts did not offer so willingly. The drawings and sculptures of Da Vinci show Italian horses (“Napolitans”) that reveal the Iberian influence on the native drafty horses (just like today’s Friesians). This is probably the circumstance in which the concept of artificial collection (or rassembler in French) was born. These ideas later became the backbone of the artistic riding style we now call “dressage” (a French word that means training, or to prepare). In Italian, the original word was “manegiare”, working by hand, that gave us the French “manege” (the riding arena and the art practiced in it) as well as the English “management”, meaning to organize and control.

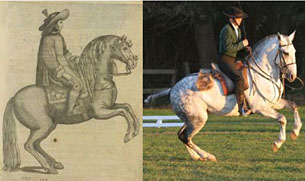

Grisone went on to teach at the Spanish Court after the 1550 publication of his book (Gli Ordini di Cavalcare or The Rules of Riding) and hence became known as the “Father of Equitation.” His book was rapidly translated many times into all the main European languages – eleven versions alone in French. Grisone’s international success demonstrates the power of the printed word (newly invented) and the early evidence than any expert must be born at least one hundred miles away from where he or she teaches. The respect this first “clinician” enjoyed in Spain stemmed from the fact that Grisone had created a (somewhat) reliable training method based on a stylized form of riding with long stirrups (known as A la Brida—in the bridle). This early version of dressage was practiced in Spain and Portugal in parallel with the more instinctive “a la Gineta” tradition, which was taught for the purpose of combat training, performed with short stirrups. It is the precursor

Grisone went on to teach at the Spanish Court after the 1550 publication of his book (Gli Ordini di Cavalcare or The Rules of Riding) and hence became known as the “Father of Equitation.” His book was rapidly translated many times into all the main European languages – eleven versions alone in French. Grisone’s international success demonstrates the power of the printed word (newly invented) and the early evidence than any expert must be born at least one hundred miles away from where he or she teaches. The respect this first “clinician” enjoyed in Spain stemmed from the fact that Grisone had created a (somewhat) reliable training method based on a stylized form of riding with long stirrups (known as A la Brida—in the bridle). This early version of dressage was practiced in Spain and Portugal in parallel with the more instinctive “a la Gineta” tradition, which was taught for the purpose of combat training, performed with short stirrups. It is the precursor

of modern sport riding. The Portuguese author Antonio Galvao de Mello wrote: “The Art of the Gineta Horsemanship” in 1678, an important book that described military exercises still practiced today by Mexican Charros, such as ‘Roman’ riding (standing on the croup of two 2 galloping horses), vaulting from horse to horse, etc.. Iberian mounted bullfighters are demonstrating today a very sophisticated version of mounted combat as a demonstration of the dressage of their horses.

Until the end of the 18th century, “La Gineta” riding was prominently displayed at the Portuguese court in the “Picaria Real” that included high school carousels, sword and pistol practice from horseback, and the famous Escaramuchas (challenge from rider to rider), an Iberian tradition that goes back to the highest antiquity and cannot be separated from the particular agility of the Iberian horse. The word traces back to ancient German,middle age Italian and French and means “to protect and defend”. Escaramuchas has given root to the English “skirmish” to describe quick horseback fighting between isolated riders. Today, the “new” discipline of “Working Equitation” is directly inspired from the dressage “a La Gineta” and the court games.

During the Renaissance, European aristocrats traveled to Naples to learn “the New Way” of riding that they brought back later to their own country. Notable among them were four of Pignatelli's most distinguished pupils. Three Frenchmen: the Chevalier de Saint Antoine (later Equerry to King Henry IV), Salomon de la Broue (author of “The French Rider”, which would become the main inspiration of Francois Robichon de la Gueriniere), Antoine de Pluvinel (who became the equestrian tutor of King Louis XIII and reported his theories in the very famous “Teachings to the King in the Exercise of Horse Riding”), and the German horseman, George Englehard Lohneysen who brought formal equitation to Germany and published the first German riding treatise, “Della Cavalleria”.

All of these pioneers, although greatly influenced by Grisone’s views, eventually rejected several of the more forceful approaches employed at the time and subsequently developed kinder methods. Pluvinel spoke of the horse’s intelligence and the need to address his capacity for comprehensionin his training. We must remember that the notion of kindness is a relative judgment that must be seen within the moral rules of a period dominated by brutal wars of religion and the exactions of the Holy Inquisition, a time in which the rule of law used torture routinely. The practice of the Italian style of dressage evolved from its rough beginnings and became known later as Equitation a la Francaise, in reference to the dominant French influence on horsemanship in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries when the School of Versailles’ ecuyers became the epitome of Equestrian Art. The notion of lightness, demonstrated by eminent trainers such a Cazaux de Nestier (inventor of the soft curb bit) and the Marquis de La Bigne, reputed to have the best hand in Europe, was explained by La Gueriniere with the notion of “descent (relaxation/cessation) of the aids” in his book “The School of Cavalry”.

All of these pioneers, although greatly influenced by Grisone’s views, eventually rejected several of the more forceful approaches employed at the time and subsequently developed kinder methods. Pluvinel spoke of the horse’s intelligence and the need to address his capacity for comprehensionin his training. We must remember that the notion of kindness is a relative judgment that must be seen within the moral rules of a period dominated by brutal wars of religion and the exactions of the Holy Inquisition, a time in which the rule of law used torture routinely. The practice of the Italian style of dressage evolved from its rough beginnings and became known later as Equitation a la Francaise, in reference to the dominant French influence on horsemanship in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries when the School of Versailles’ ecuyers became the epitome of Equestrian Art. The notion of lightness, demonstrated by eminent trainers such a Cazaux de Nestier (inventor of the soft curb bit) and the Marquis de La Bigne, reputed to have the best hand in Europe, was explained by La Gueriniere with the notion of “descent (relaxation/cessation) of the aids” in his book “The School of Cavalry”.

THE BAROQUE EQUESTRIAN SPIRIT SURVIVES THE END OF AN ERA AND MARIALVA EMBODIES THE EQUESTRIAN SPIRIT OF PORTUGAL

The observations on the equestrian versatility of Iberian horsemen of antiquity are still true today and remain pertinent to the classical tradition because they have always been able to absorb external influences and often improve on them. During the Baroque era, Iberian riders absorbed the French method and made it their own. After the Renaissance, they clearly remained superior riders to the Italians who returned to some obscurity, until Federico Caprilli produced the second (and equally great) Italian contribution to equitation: the position of the forward jumping seat that negated the undesirable effects of excessive collected work for military cross- country riding. This concept, from Tor di Quinto to Saumur, Hannover, Fort Riley or Saint Petersburg, became the universal method of all military schools across the world, and from there to the competitive world.

In Portugal, the Fourth Marquis of Marialva’s teachings at the Royal Palacio of Belem inspired the seminal book “The Light of the Liberal and Noble Art of Horsemanship which was written by Manuel Carlos de Andrade and published in 1790, fifty years after La Gueriniere’s School of Horsemanship(which it surpassed in clarity and technical value). As a rider, Marialva was unequaled in his time and rode young horses well into his later years. As a breeder, he is responsible for the glory of the breeding program in the Royal Portuguese farm of Alter do Chao that was started in 1748 by King Dom Jose I. Marialva’s work as ‘Royal Master of the Horse’ resulted in the Alter Real horses (who are still the exclusive mounts of the Portuguese School of Equestrian Art) becoming known as the best high school horses of Europe. As a man of character, he descended into the bullfighting arena when in his seventies and put to death with his sword the bull that had just killed his son. It is since that famous day, known as “the last bullfight in Salvaterra,” that bulls are no longer killed in Portuguese arenas due to a Royal edict made in the emotion of the moment.

In Portugal, the Fourth Marquis of Marialva’s teachings at the Royal Palacio of Belem inspired the seminal book “The Light of the Liberal and Noble Art of Horsemanship which was written by Manuel Carlos de Andrade and published in 1790, fifty years after La Gueriniere’s School of Horsemanship(which it surpassed in clarity and technical value). As a rider, Marialva was unequaled in his time and rode young horses well into his later years. As a breeder, he is responsible for the glory of the breeding program in the Royal Portuguese farm of Alter do Chao that was started in 1748 by King Dom Jose I. Marialva’s work as ‘Royal Master of the Horse’ resulted in the Alter Real horses (who are still the exclusive mounts of the Portuguese School of Equestrian Art) becoming known as the best high school horses of Europe. As a man of character, he descended into the bullfighting arena when in his seventies and put to death with his sword the bull that had just killed his son. It is since that famous day, known as “the last bullfight in Salvaterra,” that bulls are no longer killed in Portuguese arenas due to a Royal edict made in the emotion of the moment.

In our time, the Marialva name evokes the Baroque style of riding, the Art of the Corrida (mounted bullfight) and the seventeenth century dress still used today by bullfighters and equerries. Above all, a ‘Marialva’ is a man whose lifestyle reflects a noble character attached to traditional values. Marialva was, by all testimonies, the consummate horseman and gentleman. The last Marquis of Marialva was Dom Diogo de Braganza, eminent disciple of Nuno Oliveira and author of “Equitation of French Tradition”, recently published in English by Xenophon Press. Joao Filipe Graciosa, former director of the Portuguese School of Equestrian Art, also descends from the famous marquis.

Part II on The Shaping of Piaffe and Passage by Fashion, History and Genetics

Related Links

Mastering Lightness: Understanding the Biomechanics

Mastering Lightness: The Correct Piaffe