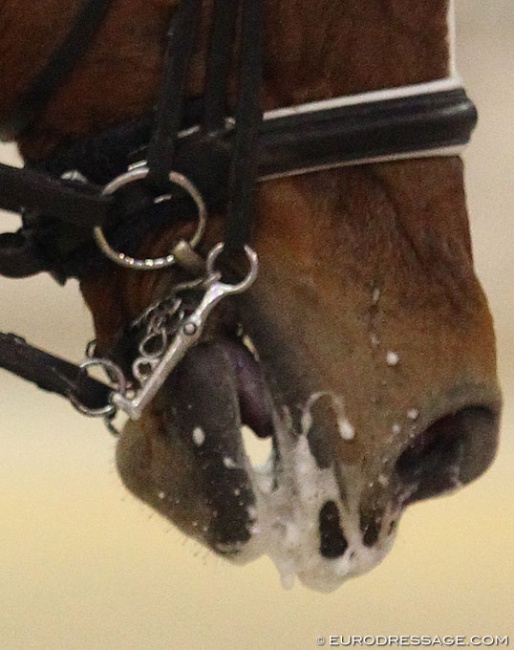

Although many riding manuals state that there should be a gap of two fingers between the noseband and the nasal plane there has been a recent trend to tighten nosebands much more than this.

Researchers F. Crago*, O. James, G. Shea, K. Schemann, and P. McGreevy of the Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney conducted a pilot study of radiographs of equine nasal bones at the usual site of nosebands. A specialist radiologist examined 60 radiographs of the front of horses’ heads at the usual site of noseband placement for any evidence of trauma. Changes were noted in 6 radiographs; 3/ 6 warmbloods, 2/ 18 Thoroughbreds and 1/ 5 stock horses.

Restrictive nosebands are of growing concern because of their putative impact on equine welfare. An informal system for gauging noseband tightness has been to check if one can fit two fingers between the noseband and the horse’s nose. In 2012 the International Society for Equitation Science (ISES) developed a taper gauge to measure this space and standardise this assessment objectively.

A recent European study revealed that 44% of all horses studied (n=750) (eventers, dressage and performance hunter horses) wore nosebands that allowed no space for the ISES gauge to be inserted between the noseband and the nasal plane.

The Study

The aim of the current preliminary, opportunistic study was to evaluate archived radiographs of equine nasal bones for evidence of trauma such as bone deposition, bone lysis, changes in bone homogeneity, bone fractures or soft tissue swelling and to test whether age, sex or breed were risk factors for such changes.

Radiographs of the nasal bones of horses (n=60) were studied by a specialist radiologist blinded to their signalment for any evidence of the described bony or soft tissue changes. Horses with described changes were classified as possible cases and horses without changes, non-cases. Possible cases (n=9) were discussed with a second specialist radiologist resulting in the reclassification by the first specialist of 3 possible cases as non-cases. The remaining cases (n=6) were matched to the signalment of each horse (age, sex, breed) by the first author and associations with being a case were assessed using chi-square tests and logistic regression analysis.

Of the 60 horses assessed, 3 of 6 warmbloods, 2 of 18 Thoroughbreds and 1 of 5 stock horses were cases. The association with being a warmblood was statistically significant (p=0.006, P<0.01) with a 39.3 times greater risk of changes than other breeds. Cases were not significantly associated with sex or age. There was lack of consensus between the specialist radiologists as to whether some changes represented normal anatomical variation and/or radiographic artefact.

However, the specialists agreed that assessing equine nasal bones using archived radiographs was surprisingly difficult due to issues such as inconsistent radiographic technique and equipment, obliquity of radiographs and a lack of objective data on what comprises normal nasal bones.

Conclusion

Any further radiographic studies in this domain should consider using a prospective sample, establish consistent radiography protocols and aim to establish normality by studying a control population, such as Australian Brumbies, that have not had human interventions.

More information at ISES

Related Links

2017 ISES Equitation Science Conference in Australia on 22 - 25 November 2017

ISES Suggest to Empower FEI Stewards to Control Tightness of Noseband

Noseband Special: Part I: The History of the Noseband

Noseband Special: Part II: The Purpose of the Noseband

Noseband Special: Part III: Riders and Trainers on Their Choice in Noseband

Noseband Special: Part IV: The Thicker, the Wider, the Better?