- by J.P.Giacomini

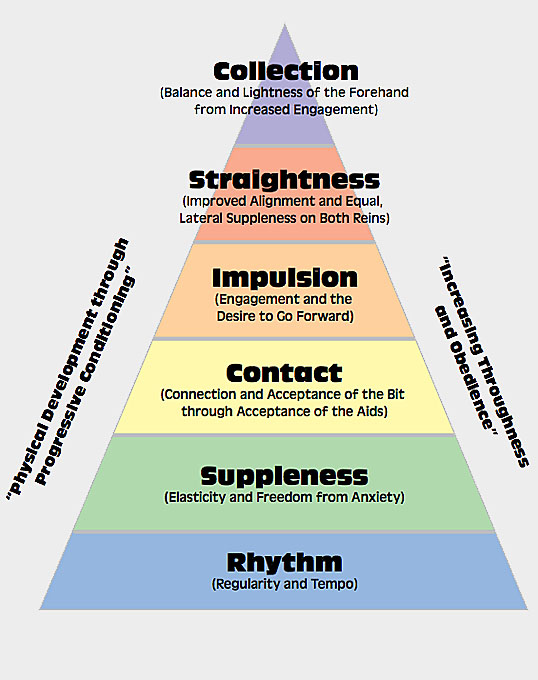

The 2019 revision of the “Pyramid of Training,” aka the Training Scale, announced by the United States Dressage Federation prompts this trainer to examine its effectiveness.

The Issues of a Scale

The newly revised USDF Training Scale sets a list of important training goals all successful dressage horses must achieve eventually. These goals—and their order—deserve serious consideration from every (dressage) rider and trainer.

They are useful to riders with a common-sense equestrian experience riding well-started horses who are safe to ride, first and foremost. They also pose challenges, as riders must be able to address problems as they arise and decide what is most important to work on right away.

My friend and Portuguese coach Francisco Cancella d’Abreu said, “Do what is hard and do it now.”This fundamental notion contradicts the training scale as a set order that tries to impose a particular progression which believers feel compelled to follow, regardless of the reality of each horse’s needs at a given time. For some breeds, or individuals, it might be the perfect order, for others not so much. As riders gain experience, they learn the rules as well as when to transgress them.

“Some will argue minor variations in the naming and order of these elements. That’s most likely because each element of the training scale works in conjunction with one or more of the other parts,” explains U.S. show jumping coach Bert de Nemethy, as quoted on Showjumpinglife.com. “One element is never used in isolation. Furthermore, while often illustrated as a pyramid or ‘building blocks,’ they should not be considered as steps where one can only be followed only upon the completion of the previous element.”

General L’Hotte’s French scale was: “Calm, Forward and Straight.” He insisted that its order must always be respected, but is it practical?

Does calmness come first? An undisciplined horse will need to be taught manners: stand, lead, back, be patient when tied, then he can be asked to go forward on the lunge and work on symmetry by working in each direction. Calm, Forward, Straight.

Does forwardness come first? A very nervous horse will need to use himself in a forward lunging session and redirect his anxious energy into symmetrical sessions to gain balance. Forward, Straight, Calm.

Does straightness come first? A resistant horse may appear calm, but will not go forward because he stands crooked and uses one of his front legs to brace himself and resists impulsion requests. Until that braced leg is unlocked and he becomes convinced to move it as much as the other, he will not go forward. Straight, Forward, Calm.

The new training scale sets valuable goals, but they will happen at different training points, according to the horse’s conformation, temperament and breed:

a flat-footed horse that lacks natural suspension (many Thoroughbreds, Quarter Horses and Andalusians, for example) will take longer to achieve elasticity, while most Warmbloods are born with it, yet may find collected gaits difficult.

Step by Step

It is difficult to achieve step 1, rhythm (regularity and tempo), without impulsion (step 4) or straightness (step 5), because a regular tempo implies symmetry of diagonal strides that cannot be achieved if the horse is not made straight by the suppling of lateral gymnastics.

Step 2’s suppleness, presented as “elasticity” and “freedom from anxiety,” represents three different concepts. Suppleness comes from lateral gymnastics and flexions (lateral and longitudinal), which cannot be achieved without the impulsion (step 4) that gets the horse to reach toward the bit—and then yield to it, which constitutes contact (step 3). Elastic gaits are either natural (in horses born with rebound) or taught by progressive collection (step 6, using “school trot” or passage) with flat-footed breeds. “Freedom from anxiety” comes from total relaxation, produced by flexions and balance—only mentioned at step 6—which comes first from uprightness (vertical alignment of the body with the pull of gravity, an important aspect of straightness in step 5 that is not mentioned in the scale).

Step 3 is contact (connection and acceptance of the bit through acceptance of the [driving] aids) which cannot be achieved without impulsion (step 4, defined as engagement and the desire to go forward).

Step 4 is impulsion (engagement and desire to go forward), which has been needed since the beginning; without the desire to go forward, how have we been training him all along? Impulsion actually has two different meanings, both necessary: “Constant desire to go forward on demand” (French version) or “Jump of the steps in trot and canter” (Schwung, German version).

Step 5 is straightness (improved alignment and equal lateral suppleness on both reins), which needs to be worked on from the start: straightness of direction and symmetry of turns should be taught before the horse is even sat on. Suppleness was already step 2.

Step 6 is collection (balance and lightness of the forehand from increased engagement). This is when the horse achieves the regularity of tempo and elastic gaits from steps 1 and 2, and can perform, with cadence, the “school gaits” slower tempo (than in the working gaits). Lightness, another name for self-carriage, demands the cessation of the aids for the horse to balance himself. This does not fit with the constant use of half-halts which are, in all doctrines, the rebalancing of unbalanced horses.

Historical Perspective

“The “Skala der Ausbildung” (the original name for the training scale) was developed from the 1912 German Cavalry Manual and the term only started being used in the 1950s

The original manual named the goals and principles for the training of a horse and provided a detailed training plan as guiding rules for the training of a military horse. The forerunner of the scale is found in Siegfried von Haugk’s 1940 book, The Training of the Recruit in Horseback Riding. In the appendix he defines the training goals in the same order as in today’s training scale:

1) Takt (Rhythm) 2) Losgelassenheit (Relaxation) 3) Anlehnung (Contact) 4) Schwung (Impulsion) 5) Geraderichten (Straightness) 6) Versammlung (Collection)

There is a YouTube video that can be found online of the Cavalry School of Hannover in the 1930s. In it, you can see pre-World War II German riding at its best, most of it centered around cavalry formations moving at speed, hunting with hounds, etc. We also see Olympic medalist Lt. Colonel Gerhardt, head of the school, training a horse for piaffe in the pillars and Otto Lörke (German team coach), head of the dressage section, working a horse in-hand at the piaffe in side-reins. Master Lörke helped Germany to its early Olympic successes and to develop a long list of successful trainers and competitors.

German dressage is what it is today because many followed his path. This unquestionable leader trained and taught differently than trainers and instructors today. Andre Montheilhet, in The Masters of the Equestrian Art, wrote: “Enigmatic, autodidact and a pure pragmatist, Lörke was an enemy of the systematic approach to training. He adapted his talent to the character and the capacity of each horse and each student. Even his most experienced students were often astonished at the training of the horses he produced when they got the opportunity to ride them after him. The horses obeyed their aids just as they did the aids of the master, which is the paramount of true mastery and a whole lot more than a simple and flattering virtuosity.”

Lörke galloped his dressage horses cross-country and jumped them on the lunge line once a week. “When all is said and done, he was the man of the exceptional demonstrations of the Dressage German School,” Montheilhet continues in this important book. “Riders will honor him and celebrate his work for generations to come.”

It is regrettable that this very simple and realistic approach to horse training and riders’ education is ignored today and replaced by the rigid dogma of a “scale” that less experienced riders feel obligated to follow to the letter. It is also evident that horses today have changed for the better, gaits have improved and the correct use of the horse’s back is now better understood, which is an improvement on the Lorke period.

Nuno Oliveira inherited from his master Joaquim Gonçalves de Miranda the same pragmatic approach to training: he wanted a horse in balance and without resistances, but was not interested in a rigid method and instead preferred to remain loosely in the “spirit of the method.” He said to me once, “I have tried everything in dressage, and just kept what works best in the function of each horse.” Nevertheless, Oliveira was obsessed with cadence, relaxation, self-carriage and “horses walking with their backs.” Correct goals and supple methodology are not mutually exclusive.

Flexion and Relaxation

Studies of equine neurology have demonstrated the horse’s general relaxation depends on the vagus nerve activity triggering swallowing, first the lifting of the tongue (bits), then retraction of the tongue backward for swallowing followed by its dropping down, licking, chewing, etc. Heavy, continuous contact and tight nosebands prevent tongue activity and the relaxation of the horse’s body and mind that depends on accessing the parasympathetic state (rest and digest, restore the immune system, etc.). Mouth relaxation during all movements (demonstrated by swallowing) is the barometer of correct training.

François Baucher never gave credit to his predecessors and got into a lot of unnecessary polemics, but at the end of the day, everybody is still following Baucher. He understood the neurologic effect of the jaw/tongue relaxation and had intuitive understanding of the future of chiropractic, as demonstrated by his work on flexions. He insisted horses must be alternately elevated and flexed during transitions from reinback to all gaits, a method used in one form or another by all successful riders today, including Carl Hester and Charlotte Dujardin.

Every good idea can be carried out past its usefulness. To be useful, a flexion suppling any part of the body must always end in complete relaxation, like yoga postures. Neck flexion arches it by lifting its base (C6/ C7) from the tension of the sternocephalic muscles on each side of the under-neck (which lift the sternum) and the brachiocephalic muscle (which lifts the elbows and pulls them forward in movement). Any flexion by pulling the head down by force and maintaining this uncomfortable position by constant pressure, with the base inverted and the topline broken at the third vertebra, does not result in any improved flexibility of the back. Instead it maintains the horse locked in a forward balance he cannot escape with completely stiff hind legs (croup high).

Aids and Submissiveness

“Submission” and “rider’s effectiveness of aids” are two line items at the end of dressage tests to be scored in the collective marks. While they are not directly mentioned in the training scale, they are important enough to require attention and evaluation by judges.

An aid consists of applying some pressure to the horse (seat, legs, bit, cavesson, whip, voice, physical presence, etc.). The horse (hopefully) responds by releasing his tension in the manner desired by the trainer, and his goodwill must then be encouraged by diminishing the intensity with every repetition. This entices the horse to do more by himself as he understands what is asked without objecting.

The difficulty is that all untrained horses resist physical pressure: it is called the “Opposition Reflex,” hence the importance of submission. At first, any stimulus is met by this Opposition Reflex (resistance). If a weak intensity stimulus is maintained (consistent pressure or a rapid tempo vibration/tapping), the muscle becomes desensitized (ignores the stimulus). In the third phase, renewed intensity triggers the parasympathetic state of relaxation (rest and digest) by stimulating the vagus nerve (which controls salivation, swallowing, so we get “chewing and licking” and stimulation of the digestive tract). After relaxation sets in, the stimulus finally gets the right response from the now relaxed muscle. As time goes, the first three phases collapse to a mere fraction of a second and the horse responds practically immediately. This is the process by which the horse “accepts” the aids: he understands, responds quickly and retains the new “neurological memory.” This results in better balance, deeper relaxation, freer movement and absence of conflict through submissiveness, all intrinsic rewards belonging to the nature of the horse that make training easier and longer lasting.

The Benefits of 'Old Fashioned' Military Training

These enormous holes in the training of dressage horses today have ushered in the expansion of American and Australian natural horsemanship, which offers solutions to the problems of dressage competitors whose horses are nervous at shows, get scared from the smallest noise or movement and occasionally bolt and/or throw their riders. In England, Holland and Germany, Australian horsemen Tristan Tucker and Will Rogers present young sport horses with impeccable behavior ridden with running chainsaws, flags or umbrellas in hand, under huge flying tarps, and trotting with no halter and lead behind their trainers through obstacle courses. Our own Grand Prix stallion, JP Zorro, is ridden by his trainer Cedar Potts without a bridle while performing Grand Prix movements at horse fairs surrounded by strange horses, thanks to elements of training that are outside the current training scale: total self-carriage without physical contact, complete trust in his rider, adaptability to unknown surroundings.

Although the training scale comes from the military tradition, it does not reflect the full scope of the training cavalry horses were exposed to. Horse training must be based on common sense and insure first the safety of the rider by immediately developing the obedience of the horse and his understanding of the job he has to perform. Albert Decarpentry, a cavalry general, revered author of Academic Equitation and co-author of the 1920 FEI dressage rulebook, insisted that the future dressage horse must first be able to walk calmly down busy streets in company of a cavalry squadron, not kick others and go boldly cross country.

Training scales and guidelines provided by national and international federations, though well founded, are often taken literally by dressage neophytes who are long on Olympic hopes and short on practical experience. This sometimes results in training dead-ends. It would be really helpful (and maybe lifesaving) to horses and riders if these guidelines made a strong point on the absolute necessity to start (or restart) the horse’s education with some solid ground work: liberty, work-in-hand, desensitization, obstacle courses, educated lunging, etc. This would help trainers bridge the gap between classical dressage, natural horsemanship, and the learning theory that emerged from operant conditioning (using rewards and aversive to shape behavior through its consequences).

dressage horse with a tarp being pulled over it.

The training scale defines important goals and appears to insist on their order of priority, but that order varies between animals with their own talents and weaknesses that need to be understood. Because riders’ abilities differ in many ways, everybody’s chosen techniques are personal. On the other hand, training principles are universal and must not be confused with goals or methods. Fundamental goals of training that border on principles include: the horse must be willing to respond as asked; be as relaxed as the moment allows and rounded in his topline to carry the rider effectively; be as symmetrical as physically possible in all exercises at the three gaits to remain sound; and be generally happy in a suitable job. More principles to follow include: “Ask often, be satisfied with little, reward generously” (Baucher); “Get the horse to appear as if he goes as of his own accord” and “Get him to enjoy himself in the exercise” (L’Hotte); and “Never deal with a horse when upset” (Xenophon).

Perhaps Josipovich and Heydebreck said it best in The Service Horse (1930): “The goal of dressage is to eliminate the stiffness of the horses’ joints, to develop their maneuverability and in particular, a facility of movement resulting from an equilibrium that allows them to go for a long time, much longer than untrained horses, while using less effort.”

by Jean-Philippe Giacomini - Article first published in Warmbloods Today.

Related Links

The Shaping of Piaffe and Passage by Fashion, History and Genetics: Part I

The Shaping of Piaffe and Passage by Fashion, History and Genetics: Part II

The Shaping of Piaffe and Passage by Fashion, History and Genetics: Part III

Mastering Lightness: Understanding the Biomechanics

Mastering Lightness: The Correct Piaffe

The History and Biomechanics of Lightness: Part 1

Flexions and Flexibility: Part I

Flexions and Flexibility: Part II