by Angelika Frömming, assisted by Silke Rottermann

Frömming is a retired German I-judge who has trained with some of the sports‘ legends and has competed up to Grand Prix-level herself. In Germany she had been responsible for the schooling of future judges for more than two decades. She still teaches future riding instructors at the German Riding School in Warendorf on the subject of equestrian history which is her hobby-horse and on which she has published a reference book in 2011.

The Shoulder-In

Having been an advanced dressage rider myself, I am aware that the way one executes a certain movement is not only dependent on what is written in manuals, guidelines or rulebooks, but on several other factors - such as a horse‘s training level, a specific goal to follow or also from the feeling one gets in the saddle.

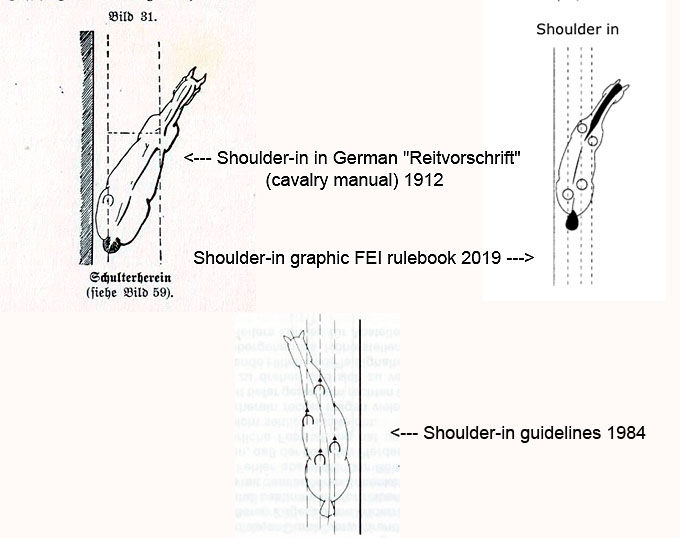

However, having now spent a considerable part of my equestrian life as a passionate dressage judge and as a trainer of future dressage judges in my home country, my eyes are focused on seeing shoulder-in like the guidelines of the German equestrian federation and the FEI dressage rulebook define it: Ridden on three tracks with the hind-legs not crossing. I didn‘t spend a second thought on this until recently two fairly, newly published books about dressage training arrived on the desk of my office at home: One based on the German cavalry manual of 1912/37, the other on classical French equitation. Both written by accomplished horsemen, both with a lifetime of experience training horses according to what everybody would consider "classical principles": The authors are Kurd Albrecht von Ziegener and Christian Carde.

What caught my eye were the drawings and photos illustrating the shoulder-in: In the German book, Die kommentierte H.Dv.12- Das Regelwerk der Reitkultur neu erklärt, the painting shows four tracks while the comment of the author points out that there should be three tracks, in the French edition translated to German, Dressurreiten. Zwischen Tradition und Moderne, the shoulder- in is constantly executed on four tracks with the hind-legs clearly crossing.

My immediate reaction was influenced by my many years in the judges‘ hut, following the rules: The ones on four tracks aren‘t really correct! My second reaction was more cautiously: I am aware that during the course of history the shoulder-in was not always executed like most of us know it today: On three tracks with non-crossing hind-legs.

The strong influence to train and ride what competitive dressage requires had also caught me at that very moment when I looked at those books. Nonetheless it was the starting point of me looking closer into the evolution of this so important lateral movement of shoulder-in, which "inventor" Francois Robichon de la Guérinière once called the "all-cure of equitation" and "the first and last movement to teach the horse in order to achieve suppleness in all his parts."

1.) Where the shoulder-in has its roots

When looking for the roots of this movement, we can trace it back to the „épaule en dedans“ of de la Guérinière in the „head in volte“. This exercise which can be considered as an imperfect predecessor of the shoulder-in, was described in the Duke of Newcastle‘s (1592-1767) 1658 published book A Central System of Horsemanship.

Seventy-five years after Newcastle it was French Francois Robichon de la Guérinière (1683-1751) who published his reference book Ecole de Cavalerie which become the basis of all classical riding that followed in the centuries to come, no matter of German, French, Austrian or Iberian origin.

De la Guérinière, who worked in the Tuileries in Paris and unlike some claim had never been member of the legendary School of Versailles at that time, spotted what the Duke of Newcastle‘s „head in volte“ was lacking: „Concerning the Duke of Newcastle (…) he himself admitted the obstacles which can be found when he says that in the head in volte the head comes in and the croup out and as a result parts of the forehand are more restricted than those of the hindquarters and that way this exercise brings a horse onto the forehand.“

The Frenchman realized the necessity of the interaction of inside leg and outside rein to weed out this weak spot and therefore discovered a movement which revolutionized the possibilities to make a horse supple, straighten it and increase his collection: the shoulder-in.

According to De la Guérinière „the shoulder-in has multiple effects. (…) First and foremost it has a suppling effect on the shoulder (…), it prepares the horse to sit on the haunches because with every step it brings the inside hind-leg under the body and puts it over the outside (…) and it teaches the horse obedience to the leg aids.” For him the shoulder-in was the ideal mean to achieve the suppleness of the whole body of a horse with the goal to perfect the natural movements.

However, de la Guérinière was also aware that it was easier for a horse to execute this movement along the wall instead of on the circle, like Newcastle did. The Frenchman also realized that in trot “there’s the danger that the horse sustains an injury at the inside, the supporting, leg.” Therefore de la Guérinière executed the shoulder-in in “a slow, but not dragging walk along the wall.”

Not long after Ecole de Cavalerie had been published and spread fast across Europe, the German cavalry instructor Ludwig von Hünersdorf (1748-1718) expressed what had been the genius in De la Guérinière: „De la Guérinière compared everything what has been said by the previous masters about the way to teach a horse to move on two-tracks. The difficulties which he found in the effects of their instructions lead him to invent the shoulder-in.“

In the decades and centuries which followed the shoulder-in became an indispensable movement in the training of a horse, but the way to execute and the point in time to introduce it began to vary with time, with the trainers who wrote their books and overall with the introduction of competitions under the wings of the FEI in the early 1920s. The shoulder-in was only included about 60 years later.

2.) The shoulder-in for Steinbrecht

German Gustav Steinbrecht (1808-1885) is generally considered the "father“ of German equitation. Until his reference book Gymnasium des Pferdes was first published in 1886, German equitation just like in neighboured France consisted of cavalry riding and training and such which followed the High School as a goal and the books written on equitation often put their focus on either side.

If today's equestrian world speaks of Steinbrecht and what he wrote, it refers to the 4th and last edition of his book which was published in 1935 after Colonel Hans von Heydebreck, a German judge and dressage rider, had edited it. So if we compare the original edition of 1886 with the most read edition of 1935 regarding the shoulder-in, we can see a significant change in the recommended angle. It shows us that around that time the discussion, which prompted my research, was already existent.

In Steinbrecht‘s first edition the shoulder-in is recommended to be executed on "four tracks to achieve the best possible bend in the horse‘s ribs and the bending of the inside hind-leg." In 1935 this is changed to "three tracks in which the inside hind-leg steps into the track of the outside frontleg."

Von Heydebreck explains that change in the chapter about the “Movements on two tracks” with the fact that the cavalry horse now has to be less collected than in the times when mankind was still fighting on horseback. As a consequence lateral movements should only be asked to an extent which is necessary to help individual horses to overcome their physical difficulties, to bring them into balance and self-carriage.

Already in the first edition Steinbrecht gives a warning not to introduce the shoulder-in too early in the training of a horse, because many horses would be spoilt by this.

This is still reflected in many books written by German authors and also in the German dressage tests, which only require the shoulder-in from the level L** on.

And there is a clear difference to the French school where we often see the shoulder-in being introduced at a quite early stage. For example French trainer Michel Henriquet (1920-2014), whose wife Catherine rode on the French team at the Olympic Games, already introduced it to his horses when they were four year olds. This could be explained by the fact that the shoulder-in not only collects, but overall makes a horse supple.

3.) The shoulder-in in the 20th century

The beginning of the 20th century until the end of World War II was still influenced by the cavalry and the national institutions which trained horses and riders for war time. Between both World Wars the foundation of the FEI and the introduction of international competitions, also in dressage, led to a development that increasingly saw the competition world and their needs taking a big and finally dominant influence.

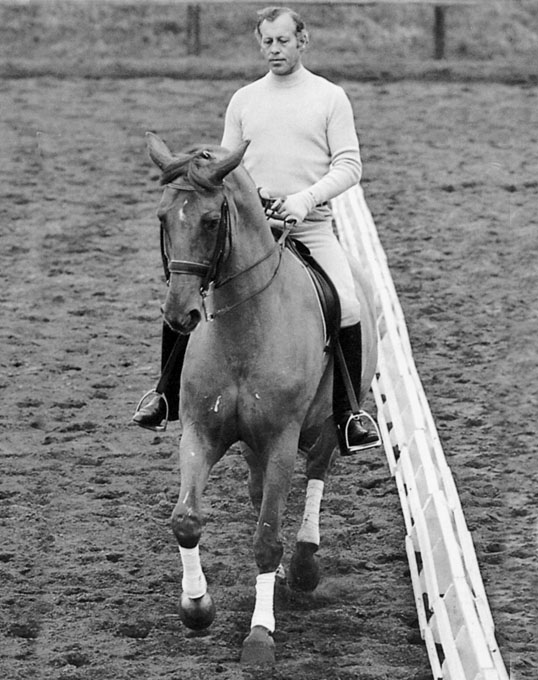

by Harry Boldt in 1978

This fear of a loss of impulsion when putting the horse on different tracks is mentioned in more than just one book, as it robs the shoulder-in of every of its many benefits.

Oskar Frank (1894-1963), the Swiss chief instructor of the Swiss cavalry school in Berne and who was a very influential personality for Swiss dressage in the first part of the 20th century, wrote a kind of equivalent to the German cavalry manual, called Reitvorschrift. It was part of a bigger book about training troops. Written in 1939 it not only emphasized the benefits of the shoulder-in: the correct longitudinal flexion, the increasing of the obedience to the leg aids and increased collection. It also stressed this valuable lateral movement as a mean of correction, in particular if a horse isn‘t accepting the bit or the rider‘s leg aids. Here Frank indirectly refers to the relaxing effect the shoulder-in has on the horse‘s jaw joint because it initiates the horse‘s natural strive to yield to the inside, which De la Guérinière had also recognized. Frank, just like the German cavalry manual, follows De la Guérinière in that he lets the shoulder-in be executed on four tracks with "the inside feet crossing in front of and over the outside."

The rider‘s obligation is to constantly check if the frame of the horse is corresponding with the horse‘s activity. For that reason Frank recommends always to only briefly exercise shoulder-in, because otherwise there is the danger of a loss of rhythm. He also wanted it to vary with ground-covering gaits which foster impulsion.

While most authors until that time follow the shoulder-in-father De la Guérinière in that they execute the movement on four tracks with the hind-legs crossing, it is to no surprise that Colonel Alois Podhajsky, the Spanish Riding School‘s charismatic leader through war times until 1964, also remains faithful to the Frenchman on whose teachings the SRS is based on. In his remarkable book Die klassische Reitkunst, published 1965, Podhajsky refers to De la Guérinière's shoulder-in as the common practise at the SRS with all legs crossing on four tracks. He also warns for the dangers the rider has to be aware of: „During the execution one has to take special care that the outside hind-leg isn‘t stopping to act and escaping the bend.“ Podhajsky stressed that the shoulder-in is indispensable on the way to bend the haunches so that the hind legs carry more weight. As a result the shoulders get freer, the contact lighter, and the whole gait improves. He mentions that in the SRS at his time the shoulder-in isn‘t taught in walk, but always in trot „because every lateral movement requires impulsion and there is more of it in trot than in walk.“

General Decarpentry, the multiple Olympic judge from France and author of the first FEI dressage rulebook, wrote the well respected book Academic Equitation in 1949. Decarpentry warns that the shoulder-in is "of no use unless the forehand and the hindquarters remain exactly on their respective tracks." To achieve this Decarpentry mentions the necessity of gradually increasing the angle and bend: "At the beginning the angle must be (…) very light (3 tracks). Gradually the degree of incurvation and the distance between the inside and the outside track must be increased.“ (according to the drawing up to four tracks). He also speaks about a limit that is „(...)when the outside hind tries to escape from the track and turns out instead of advancing forwards."

In the 1970s double Olympic champion Harry Boldt published an extraordinary book on dressage training called Das Dressurpferd which stood out with a new way of illustrating the different movements in photo series and from different angles. There the shoulder-in is constantly shown in trot and on three tracks. Boldt writes „the international rule is like that that the horse executes the shoulder-in on three tracks, whereas it had been shown on four tracks abroad in the past.“

4.) The shoulder-in in national guidelines and the FEI dressage rulebook

Foreign experts love to define what they assume is “German equitation” with our national guidelines which are now written down in 6 volumes. Of those only volume 1 and 2 are of relevance when we speak about dressage riding.

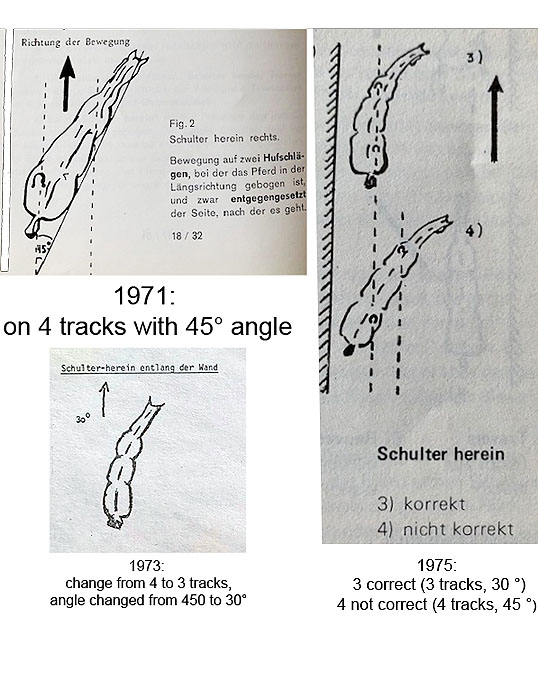

The description of the shoulder-in is to be found in volume II of which the first edition was published back in 1967. There it is shown and defined with an execution on four tracks which didn’t change until its 9th edition in 1984 when the text describes the movement for the first time on three tracks. This has been kept in all editions ever since.

The FEI rules were created and first written in the 1920s in order to achieve more credibility of this organization at its beginning and to give judges help how to judge the different movements, which at that time sometimes looked quite different, depending on the School the riders belonged to. Until its 14th edition in 1975, the FEI dressage rulebook described and drew the shoulder-in as a lateral movement executed on four tracks (with a 45 degree angle), like the original descriptions of De la Guérinière. However, surprisingly, shoulder-in wasn’t considered as a (competition) movement in itself, but as “a preparative exercise for other (…) lateral movements which basis it is.”

Former Swiss I-judge and former head of the Swiss Cavalry School in Berne, Pierre-Eric Jaquerod, comments that “De la Guérinière called the shoulder-in an exercise, a means to achieve a goal: train the horse to move sideways and to foster the bending of the hindlegs. For that reason it wasn’t asked for in competitions in the past, but only what this exercise produced: Lateral movements and higher collection, like piaffe and passage.”

In 1973 some changes in the 13th edition (of 1971) concerning the shoulder-in were published: The shoulder-in is now described as a “lateral movement” and is shown as a movement with an angle of about 30 degree.

From its 14th edition in June 1975 onwards the FEI stipulates that “the horse in the shoulder-in should not show an angle of more than 30 degree.” In the same year the shoulder-in was included as an official movement in the FEI dressage-tests.

For former Dutch Olympic jumping medalist and renowned dressage trainer in his later years, Henri van Schaik (1899-1991), this introduction was the beginning of the shoulder-in’s downfall in dressage training. In his well-respected book Misconceptions and Simple Truths in Dressage he states that the riders of our days think more about what judges want to see than about what purpose the shoulder-in has.

What is definitely striking are the drawings which should illustrate the shoulder-in in these rulebooks of the 1970s. Partly shoulder-in was shown as a kind of leg-yielding over 4 tracks. What was considered the correct shoulder-in in the 1971 edition is shown as “wrong” shoulder-in just four years later.

Apart from the technical difficulties to draw correct movements back then, it surely shows the confusion about this movement at that time. However, neither judges nor trainers, nor riders could get much help from such questionable drawings and the same is valid for the post war manuals in which drawings were even less clear.

In its latest version as of 1st January 2019, the FEI dressage rulebook continues to describe the shoulder-in as a lateral movement ridden on three tracks “with a slight, but uniform bend (…) and at a constant angle of approximately 30 degree. The horse’s (…) inside hind-leg (…) is following the same track of the outside frontleg.”

Pierre-Eric Jaquerod sums up that “the rule which is valid today: three tracks with bending isn’t completely what the shoulder-in had been like in its original form, but it has the advantage that it can be measured more easily: “The bend is visible because the front legs cross, but the hindlegs not and the angle is easier to be recognized, because there are 3 tracks, no less and no more. Therefore shoulder-in can taught and judged more objectively.”

5.) Three or four tracks?

It is undoubtable that the determination of a shoulder-in ridden on three tracks in the national guidelines and over all in the FEI dressage rulebook as well as its inclusion in international dressage tests had its effect on how this movement is trained and ridden nowadays.

However, while the competition world needs clear rules, there‘s more clearance to play with angle and bend in a horse‘s training and that is good for a reason. And all riders should make good use of this and not just train for a certain class they aim to compete in, as this would be a dangerous one-way-street.

What is remarkable is that during my research on the topic I found contradicting opinions of highly accomplished horsemen on the matter, in particular on how many tracks to execute shoulder-in.

Already in 1965 Alois Podhajsky expressed the opinion that the purpose of the shoulder-in gets lost if it is ridden on only three tracks. „Like that, the shoulder-in is only indicated (…) and the inside frontleg crosses insufficiently." This, of course, corresponds to De la Guérinière who, with the help of the Duke of Newcastle’s earlier findings, realized that the shoulders can only really be suppled, if the inside hind-leg crosses over the outside one.

Contrarily to the legendary former leader of the SRS, renowned German trainer Kurd Albrecht von Ziegener (1918-2006) mentions at the beginning in a book written with Dr. Gerd Heuschmann that the shoulder-in on four tracks contradicts with the purpose of the shoulder-in and collection. His co-author Dr. Gerd Heuschmann explains it as following: “requesting the shoulder-in with an angle of one step (= tracks) causes with modern, big moving horses a failure of the inside hind-leg, a loss of bend in the rib-cage or a break out via the outside shoulder. Often a wrong leg-yielding arises.”

So what, the attentive reader my ask?!

Colonel Hans von Heydebreck‘s statement, which he laid down in his booklet The German dressage competition in 1928, seems reasonable. In this booklet he describes how the dressage movements which were requested in the classes back then, should look like. Regarding lateral work he mentions that due to the angle the driving power of the hind-legs gets restricted in favour of the carrying power. Consequently von Heydebreck stresses that „the angle orientates itself at the degree of achieved longitudinal flexion.“ In other words: The more carrying power a horse has, the more collection he has, the greater an angle is possible which von Heydebreck limits to four tracks as a maximum, as this seems to be the biomechanic limit for most horses before their hind-leg inevitably escapes.

Another interesting thought comes from French dressage trainer Jean-Claude Racinet (1929-2009) who was a well-known representative of the Baucherist system, based in the USA. For him it is of no great importance if the shoulder-in should be ridden on three or four tracks, because for him the number of tracks is dependent on the size of the rectangle which the four legs create and logically this differs from horse to horse.

A pretty similar opinion is shared by his compatriot Christian Carde (*1939), former chief rider of the Cadre Noir and like me a retired I-judge. He stresses in a letter to me that the individual conformation of a horse always needs to be considered and a rider has to feel which angle to choose in the shoulder-in in order to get a positive effect. Carde also points out that while many refer to De la Guérinière’s original shoulder-in on four tracks, it is often forgotten that he had described the shoulder-in in walk, whereas today it is often ridden in trot which is more demanding for a horse that hasn't been made so supple. “For a well trained and supple horse it usually doesn’t pose a problem to do shoulder-in in trot and on four tracks”, he stated.

Conclusion

As a judge or a competitor it is undeniable and obvious that formalities are important as they create a necessary guideline for both sides and therefore give some security what to show and what to judge. A rider has to be aware at all times that in a horse‘s training formalities are not decisive, but entirely what will the horse‘s training do good and improve him and his performance.

As so often, the rider‘s skillful knowledge is the thing which is first and foremost required when taking the right decision which degree of angle and bend to choose for a specific horse. Most important is that the quality of the movement (including rhythm, suppleness, contact, impulsion, straightness and for an advanced horse collection) is always maintained which is the best indicator if a rider has made the right choice.

And in order not to get into the danger of which Podhajsky spoke, retired O-judge Heinz Schütte (my judges‘ colleague), always advised: „Better a bit more than not enough.“

The good rider will feel when his horse achieves all the benefits De la Guérinière‘s stroke of genius can produce.

By Angelika Frömming with Silke Rottermann

Photos by Silke Rottermann and with kind permission of FN Publishing House, taken from: Harry Boldt, Das Dressurpferd, Warendorf 2011.

Related Links

Angelika Fromming: Half a Century of Dressage

Angelika Fromming: Open Scoring and Expert Commentary to Popularize Dressage

Fromming & Stammer Seminar 2016: A Get-Together of Biomechanics and Classical Dressage Training

Q & A Session on the State of Dressage with I-Judge Angelika Fromming

Functionality in Equitation: Aim for Good Movement

Classical Training: The Shoulder In

Bibliography

- Boldt, Harry, Das Dressurpferd, 6th edition, Lage-Lippe 1978.

- Carde, Christian / Rottermann, Silke, Dressurreiten. Zwischen Tradition und Moderne, Hildesheim 2019.

- Carde, Christian, Personal letter to Angelika Frömming in February 2019.

- Decarpentry, General, Academic Equitation, London 1971.

- Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung , Richtlinien, volume II, 9th edition, Warendorf 1984.

- Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung, Deutsche Übersetzung der Bestimmungen der FEI (Teil IV-Dressur), 13th edition, Bonn 1971.

- Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung, Deutsche Übersetzung des ‚Règlement des Concours de Dressage‘, Warendorf 1975.

- FEI dressage rulebook 2019 (24th edition of 2014 with updates of 1st January 2019): https://inside.fei.org/sites/default/files/FEI_Dressage_Rules_2019_Clean_Version.pdf (p. 20 / 21)

- Frank, Oscar, Reitvorschrift (reprint), Winterthur 1997.

- Guérinière, Robichon Francois de la, Die Reitschule, Daudenzell o.A.

- Hauptverband für Zucht und Prüfung deutscher Pferde e.V., Richtlinien, volume II, 1st edition 1967.

- Heeresdienstvorschrift (H.Dv.) of 18th August 1937, Berlin 1937.

- Henriquet, Michel / Durand, Catherine, Henriquet on Dressage, North Pomfret 2004.

- Heydebreck, Hans von, Die deutsche Dressurprüfung, 3rd edition, Berlin and Hamburg 1988.

- Jaquerod, Pierre-Eric in an e-mail to Silke Rottermann on 9th March 2019.

- Josipovich, General a.D. Sigmund von, Steinbrechts „Das Gymnasium des Pferdes“ in der Bearbeitung von Oberst Hans von Heydebreck, published in:

- Deutsche ST.GEORG Sportzeitung, first January issue, Berlin 1936.

- Loch, Sylvia, Dressur. Die Kunst der klassischen Reitweise, 2nd edition, Stuttgart 2010.

- Podhajsky, Alois, Die klassische Reitkunst, München 1965.

- Reitvorschrift of 29th June 1912, Berlin 1912.

- Schirg, Berthold Dr., Die Reitkunst im Spiegel ihrer Meister, volume I, Hildesheim 1987.

- van Schaik, Henri Dr., Misconceptions and Simple Truths in Dressage, 2nd edition, London 1989.

- von Ziegener, Kurd Albrecht / Heuschmann, Gerd Dr., Die kommentierte H.Dv.12- Das Regelwerk der Reitkultur neu erklärt, Stuttgart 2017