by Angelika Frömming for Eurodressage

Last spring I had the pleasure of commenting on the Grand Prix test for the Personal Members (PMs) of the German Equestrian Federation at the Dortmund indoor show. The organizer allowed access for seminar participants to the VIP area, taking the precautionary measures into account, despite the ban on spectators right at the beginning of the corona pandemic.

Commenting on the Piaffe at the 2020 CDI Dortmund

As a commentator you experience a dressage test differently then when you sit at the judge's table. You feel relaxed and interested somehow as you do not have to mentally rush from one movement to the next, or allocate individual marks in quick succession, comment on them if necessary, and weigh and assess what happens between the individual movements. You have the freedom to focus on certain observations and time to explain which movement should be carried out how and why it probably did not work. These "information seminars" are about explaining dressage as gymnastics of the horse to the passionate listeners, detailing the meaning of the individual movements and showing how the harmonious interaction between rider and horse can and should be achieved.

In the course of such a seminar, participants can think about individual movements, their evolution in history, the assessment criteria and general practicality. And there is also the possibility of checking individual assessment criteria for their accuracy, without constantly keeping an eye on the overall package of all judging aspects that determine the mark of a movement.

The movement that was of particular interest at this year's Dortmund indoor show was the piaffe and its criterion "with spring" from the FEI rules and the statement from the German guidelines for riding and driving "a short holding moment in free suspension". This raised the question whether the moments in free suspension can always be clearly recognized and what the consequences are if you cannot recognize them.

And since the piaffe is often presented in very different forms at the shows, the recurring question came up whether and how far the conformation of the horse influences the execution of a piaffe and must it, therefore, also be taken into account in the judgement.

The piaffe is a Means to an End, Not an End in Itself

A look into the past is always interesting for those interested in history. It starts with the question from where the term “piaffe” comes from.

According to Jean-Philippe Giacomini - "The shaping of Piaffe and Passage by Fashion, History and Genetics Part II", the term piaffe comes from the Italian "de piedo fermo" and means something like "trot on the spot". French students adopted the Italian term during the Renaissance and made the abbreviation "pie-fer," from which the term "Le Piaffer" developed in France. In German language usage, "le Piaffer" became "the Piaffe".

According to Ulrich Schnitzer, a piaffe that was shown more in the forward movement was also called a "small passage“ in the past.

The next question is why it makes sense at all to train the horse up to the piaffe and then to request it in dressage tests of the highest class. Basically, the piaffe is a natural, often emotionally induced movement of the horse in nature, so nothing unnatural. On the question of why the piaffe is required in the highest dressage classes, Christian Carde, grandseigneur of the French school and former international dressage judge, makes a clear statement in his recently published book "Dressage Riding Between Tradition and Modern Age, How Riding Art and Sport Harmonize“:

"The gradual development and later execution of the piaffe serves to perfect the collection and thus improves the balance, mobility and keeps the horse ridden healthy. In addition, the improvement of balance and mobility also leads to a special majesty of the gaits."

in 1995 (Photo © Alain Laurioux)

In his book, Christian Carde points out a special point of view when working on increased collection:

"The movement tends to be slowed down, at the same time the activity of the movement is to be increased while maintaining the mental relaxation. Here only calmness and trust can lead to success."

According to Christian Carde, the collection of the "modern French school" has its origins in the second method of Baucherism: "Raising the neck in combination with engagement of the hindquarters lightens the forehand."

For Gustav Steinbrecht, the elevation during increased collection is achieved through the engagement of the hindquarters by saying correspondingly that the bending of the poll must never be sought and achieved directly, meaning by actively pulling with the hand. Rather it should be obtained through the impulsion generated by the hind legs. Both approaches assume that the shortening or closing of the framework ultimately has to be done through increased involvement of the hindquarters.

The piaffe is therefore not an end in itself, but the result of a long training to enable the horse to carry the rider's weight lightly, with grandeur and over a long life.

Ulrich Schnitzer writes in an article "Piaffe without collection?" among other things:

"So for the 'old school' the value in piaffe work lies less in achieving the movement as such, but rather in the possibility to foster, through the useful application, thoroughness and collection in the course of dressage training."

In the so-called classical equitation, the piaffe is a means to an end to gymnasticize the horse, to improve the carrying power in collection and the throughness of the horse. Thus, for the "classics," the piaffe is also the resulting preparatory exercise for the passage, which should be based on collection and not on tension.

In the end, the piaffe is in fact the preparation for the Levade.

Visual Appearance of the piaffe

In addition to the passage, the piaffe was part of the Olympic program for the first time in Los Angeles in 1932, a challenge for all potential participants, as there were hardly any "good and clear traditions" available for these movements.

In an article in St. Georg in 1932, Count von Holzing-Berstett referred to the directional advice given by the Cavalry School of Hanover, the school of Oskar Maria Stensbeck, the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, and Colonel Decarpentry's manual „Piaffer et Passage“ (1932). The latter was the very first author in history to dedicate a whole booklet on the training of these two demanding High School movements and it is interesting to note that Decarpentry, a multiple Olympic dressage judge from France and author of the first FEI rule-book, wrote it for the sole purpose to help French riders to train their horses in these movements.

Gustav Steinbrecht writes about the correct execution of the piaffe:

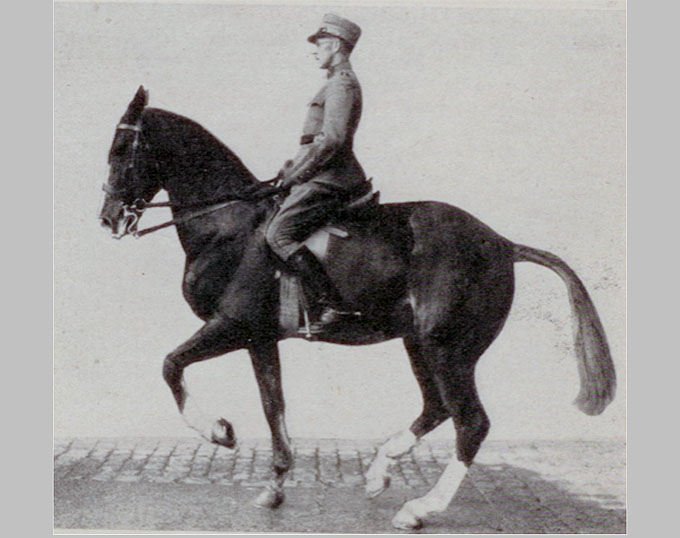

What it should look like: The horse piaffes so to say on the hindquarters

, the front leg is in the vertical. Clear uphill tendency,

the neck wonderfully arched, poll the highest point.

Everything appears elastic-supple-harmonious. One ear listens

to the rider, the other perceives the surroundings.

Stallmeister von Holleuffer commented on the height of the hind-leg in the piaffe. Holleuffer served at the Royal Military Riding Institute in Hanover, where they preferred horses of a long rectangle type:

"But the hind leg must not be lifted so high, because otherwise the horse would not be on its haunches, but the toe of the raised foot only has to go to the middle of the fetlock joint of the other leg.”

Berthold Schirg assumes in his book „Die Reitkunst im Spiegel ihrer Meister," that Holleuffer only argued like that in order neither to criticize the breeders nor the state at the time.

In the 1930s, Ludwig Zeiner, then a retired rider from the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, wrote in an article in St. Georg correspondingly:

- The most important moment of the trotting movement in place is the maintenance of the pure basic gait.

- The movement of the trot on the spot must be demanded in a straight line.

- The hind-legs must not work stilted, but must swing elastically to support the weight.

- An intermediate step is completely impossible.

but the horse is significantly over bent,

so it is neither able to step up energetically nor

take weight with the hindquarters, elasticity

becomes impossible.

Henri St. Cyr, the 1952 and 1956 double Olympic dressage champion from Sweden, explained the visual appearance of the piaffe at the general meeting of the German Judges Association in 1953 as follows:

"The horse moves (...) whereby the front-legs are mutually raised so that the forearm is horizontal, while the hind leg is just slightly above that fetlock of the resting leg. The legs should withstand a short moment when they reach the highest height, so no hasty steps. (…) The piaffe is a diagonal swinging trot, the diagonal pairs of legs alternating on the floor."

Debate About the Definition

During that time the FEI revised its guidelines and General Decarpentry from France and Dr. Gustav Rau from Germany were once again the leading figures in a commission entrusted with this revision. The late John Winnett, multiple US team rider in the 1970s and a very classically educated man familiar with the French and German approach of dressage, mentioned in his book „Dressage as Art in Competition“ that between the General and the Doctor a dispute took place over how to define the place. Whereas Decarpentry wanted to have it defined as a "passage on the spot" in order to have correct passage-piaffe-passage transitions executed, Dr. Rau opted for the "very collected trot on the spot" definition. While Decarpentry’s definition corresponded with those of old masters, it was Rau’s proposal which was finally adopted by the FEI. The legendary German hippologist justified it with the argument that horses couldn’t sufficiently lower their haunches when brought back on the spot in passage.

In classical equitation the piaffe serves as the pre-stage of the levade.

Here we see a clear uphill tendency, taking weight of

the hindquarters, an energetic bend of the joints,

the head in front of the vertical and the

poll the highest point, even though the underneck muscle

seems a bit pronounced here.

"The piaffe is a movement executed in the footfall of the trot without gaining ground cover and suspension, in which the thrust is completely transformed into an evenly distributed carrying power and spring force on the two hind-legs. With complete throughness, this results in a raised and sustained trotting movement on the spot. The horse’s head is on the vertical and the poll flexed, chewing and in a steady soft contact without nodding the head, so that his rider is always able to….initiate the levade.“

In a contribution in St. Georg magazine in 1960, Erich Glahn describes the comments that the retired General Niemack had given on the occasion of an international judges' meeting about the execution of the individual rides at the Olympic Games in Rome. Using the example of one of the Grand Prix horses there, he then demonstrated that movements such as piaffe, passage and canter changes in series can be carried out functionally correctly, but at the same time a completely tense and firm back could be detected in trot. It was obvious that while judging the Olympic rides, the judges' focus was primarily on the formalism of the respective movement, without paying sufficient attention to the overall picture of the horse presented. "For the Grand Prix a completely rideable horse is required, which has been subjected to a systematic, gymnastic training, and whose training is based on the tradition of a classical principles."

In General Niemack's opinion, a judge must be able to distinguish the leg mover from the back mover and express the result in an appropriate judgement / marking.

The Piaffe According to the FEI in 2020

In the course of the past decades the international rule-book presented an increasingly detailed description of the visual appearance of the piaffe. In the dressage rule-book of the FEI for the year 2020 the piaffe is most recently defined as the following:

- Piaffe is a highly collected, cadenced, elevated diagonal movement giving the impression of remaining in place. The horse's back is supple and elastic. The hindquarters are lowered; the haunches with active hocks are well engaged, giving great freedom, lightness and mobility to the shoulders and forehand. Each diagonal pair of legs is raised and returned to the ground alternately, with spring and an even cadence.

- In principle, the height of the toe of the raised forefoot should be level with the middle of the cannon bone of the other supporting foreleg. The toe of the raised hind foot should reach just above the fetlock joint of the other supporting hind leg.

- The neck should be raised and gracefully arched, with the poll as the highest point. The horse should remain „on the bit“ with a supple poll, maintaining soft contact. The body of the horse should move in a supple, cadenced and harmonious movement.

- Piaffe must always be animated by a lively impulsion and characterised by perfect balance. While giving the impression of remaining in place, there may be a visible inclination to advance, this being displayed by the horse's eager acceptance to move forward as soon as it is asked.

- Moving even slightly backwards, irregular or jerky steps with the hind or front leg, no clear diagonal steps, crossing either the fore or hind legs, or swinging either the forehand or the hindquarters from one side to the other, getting wide behind or in front, moving too much forward or double-beat rhythm are all serious faults.

The aim of piaffe is to demonstrate the highest degree of collection while giving the impression of remaining in place.

Additionally the essentials of piaffe had been listed in the Dressage Handbook for Judges in its first edition of 2016:

- Cadence and regularity

- Elasticity and spring

- The lowering of the haunches

- Collection (maximum carrying power of the hindquarters)

- Balance

- Giving the impression of remaining in place

- Specific number of steps

- Consistent, elastic contact and performed in true self-carriage

look one recognizes the backwards pointing right front leg which

prevents an uphill tendency. This backwards pointing front

leg indicates all too often a lack of balance and brings the horse

on the forehand, the poll dropping then. This way of

executing a piaffe can be seen more frequently in competitions

today.

Coming soon: Part 2 of The Essential Guide to the Piaffe

by Angelika Frömming, edited by Silke Rottermann for Eurodressage

List of References

- Jean-Philippe Giacomini, The Shaping of Piaffe and Passage by Fashion, History and Genetics, part II

- Ulrich Schnitzer, „Prüfstein Piaffe“, in: St. Georg 12 /1996,

- Ulrich Schnitzer Titel: „Piaffe ohne Versammlung“. Christian Carde / Silke Rottermann, Dressurreiten zwischen Tradition und Moderne, Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 2019.

- Gustav Steinbrecht, „Das Gymnasium des Pferdes“, 4. und folgende Auflagen, überarbeitet von Hans von Heydebreck. Freiherr Max von Holzing-Berstett, Sankt Georg Bücherschau: „Piaffer et Passage des Oberst Decarpentry (Compiègne)“, St Georg XXXIII Berlin 1932, 2. Novemberheft

- Berthold Schirg, Die Reitkunst im Spiegel ihrer Meister, Band 2, Olms Verlag, Hildesheim 1992. Ludwig Zeiner, „Piaffe und Passage, Gänge der Hohen Schule, im internationalen Olympia-Programm“, St. Georg, XXXVI Jhg., Nr.: 29, Berlin 1936, Erstes Märzheft

- Henri St. Cyr, Mitteilungsblatt der deutschen Richtervereinigung 1953. Waldemar Seunig, Schulmäßige Versammlung, Piaffe und Passage, Übergänge und Kür, St Georg 15. Mai 1960

- FEI Dressage Rules 2020: https://inside.fei.org/sites/default/files/FEI_Dressage_Rules_2020_Clean_Version.pdf

- Harry Boldt, Das Dressurpferd, Lage Lippe 1978.

- Kurt Albrecht, Über den Sinn der FEI Dressuraufgaben, „reiter&fahrer“, 5 / 1983

- https://murdochmethod.com/suspension-part-ii-the-perplexing-piaffe/

- FEI, Dressage Handbook, Guideline for Judges, 1st edition, 2006. Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung, Richtlinien, Band 2

- Richtlinien für reiten und Fahren, Ausbildung für Fortgeschrittene, Warendorf 1984.

- Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung, Richtlinien, Band 2, Richtlinien für reiten und Fahren, Ausbildung für Fortgeschrittene, Warendorf 1987.

- Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung, Richtlinien, Band 2, Richtlinien für reiten und Fahren, Ausbildung für Fortgeschrittene, Warendorf 1990. Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung, Richtlinien, Band 2, Richtlinien für reiten und Fahren, Ausbildung für Fortgeschrittene, Warendorf 1997.

- Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung, LPO, Warendorf 1997/1998.

- Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung, LPO, Warendorf 2008.

- Jytte Lemkow, Leserbrief in: St. Georg 2019, Ausgabe 1/2019 p.6

- Jon Winnett, Dressage as Art in Competition. Blending Classic and Competitive Riding, The Lyons Press, Gilford 2003.

Photos

- St. Georg magazine

- Alain Laurioux Private Collection Angelika Frömming

- Piaff / Liselott Linsenoff taken from: Angelika Frömming, Bilder und Fakten zur Entwicklung und Ausbildung von Reiter und Pferd im Dressur- und Springreiten, Warendorf 2011, with friendly permission of FN Verlag, Warendorf.

- Alain Laurioux / ENE

- Eurodressage