-- as reported in the WBFSH State of the Industry Report 2023

Managing foal weaning has been through a trial-and-error practical approach since breeding horses became domestic. Currently, more scientific research has been undertaken to look into alleviating “weaning stress” by decreasing the potential psychological, physical and nutritional stressors associated with domestic weaning.

By observing and studying feral and semi-natural domesticated herds, scientific-based conclusions can be made to reduce the short- and long-term negative outcomes from weaning. Observed natural weaning occurred between 8-11 months old. There was no induced stress response from either the foal or the mare and there were no clear signs of rejection by dams just before or after weaning.

Artificial Weaning

The origins of early artificial weaning may have arisen from the thought of best optimising the foal's physical development as material milk production decreases sharply by the third month of lactation23 and the nutritional requirements of a 3–4-month-old foal exceeds the level of nutrients available from maternal milk. This practice was widespread in professional breeding farms and followed by nonprofessional breeders. Recently, the reasons for early weaning have followed this practice have altered, and are based around early marketing of foals, switching foals' attention from mother to humans25, management of foals' nutritional intake or optimising mares' reproductive efficiency. Early weaning is associated with many if not all of the following changes: maternal deprivation, social isolation, environmental and social changes, more intense human intervention, abrupt nutritional challenges, and changes in feeding and management practices.

Increased Stress

Natural Weaning

A recent study of a semi-natural herd of Icelandic mares and foals have found that natural weaning takes place gradually over several months with a gradual increase in the mare-foal distance and progressive decrease in suckling frequency with a change to a more varied diet and development of a larger social network. Foals are not weaned before the age of 9-11 months or before the birth of the next foal. The dam-offspring bond remains for a long time after nutritional separation. The ages at weaning vary considerably and can be due to the reproductive status of the mare. Pregnant mares tend to wean their foals on average 3-4 months before the birth of the next foal, non-pregnant mares tend to nurse their foals for a longer time. Previous breeding status of the mare, and the presence of yearling will initiate faster weaning. Also, the availability of food resources and weather conditions and maternal body condition are potential factors. The mare-foal distance and suckling activities are mainly due to the foal's initiatives and there are variations among foals due to more of a closeness to dams rather than peer interaction. The main factor in the age of weaning is the conception rates of the mares, but in this study most of the mares were pregnant again and were in the presence of their foals and yearlings. There was no loss of body condition despite the harsh climatic situations and the absence of good supplements other than hay.

Gradual Weaning

Responses such as classic behavioural and physiologic signs of stress, foal-to-foal aggression, higher cortisol concentrations, and weight loss, can be mitigated with better weaning techniques. Group weaning is associate with a lower incidence of behavioural indicators of stress, if the animals are thoughtfully grouped together. It has been shown that the importance of artificial weaning lies not in the age of the foal or the preparation of the feeding transition, but by paying attention to the strength of the social bond between mother and foal.

Conclusion

Although more scientific research is required for what constitutes best practice in respect to animal welfare for weaning in the domestic environment, improvements to the management of domestic horses regarding weaning needs to be addressed. Current methods have been shown to lead to short and sometimes long-term severe negative outcomes of domestic horses. More research is needed to understand these long-term impacts of weaning on trainability and later maternal behaviour, and other detrimental effects on the performance horse.

Source: WBFSH State of the Industry Report 2023

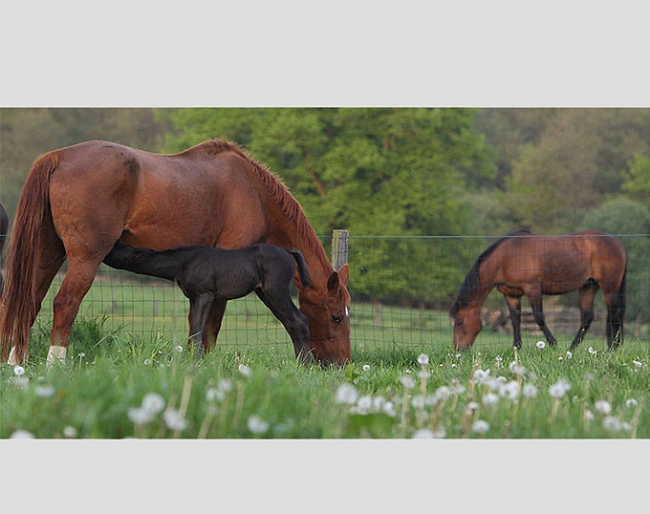

Photos © Astrid Appels

Related Links

Horses and Abnormal Behaviour Investigated in Three Counties in Sweden

Feeding the Equine Athlete Discussed at 2015 European Equine Health & Nutrition Congress

Good Horsekeeping at Gut Schönweide: Social Boxes for Stallions based on Swiss Research

Good House Keeping: Finding the Right Balance in the Management of Dressage Horses

FN Training Seminar with Hess and Graf: "Quality Equitation Leads to Success"