How many dressage fanatics still associate something with the name Gustaf Nyblaeus; a name which was house-hold in the dressage community until 25 years ago? The life and work of Colonel Gustaf Nyblaeus should not be forgotten. He was a man who influenced dressage in a remarkable way and who still holds a record which might never be equalled: judging Olympic Games for twenty years in succession.

When Nyblaeus was born on 11 December 1907 in Skövde, Sweden, the Olympic Games -- the celebrated event in which he would set his foot steps so firmly and impressively -- had not even opened up to equestrian sport. Five years later though the capital of his home country Sweden opened its doors to four-legged Olympians.

Cavalry Beginnings

The 1912 Olympics in Stockholm marked the birth of today's equestrian disciplines of dressage, jumping and three-day-eventing in the Olympic programme and the 5-year old Gustaf Nyblaeus was already an attendant back then. Young Gustaf was able to live this early Olympic experience as his father was the chairman of the Jury of Appeal for the equestrian events. Born into the family of a general-major of the Swedish cavalry, the boy grew up with horses and got his first pony soon after the 1912 Olympics. It seemed logical that a young man with an interest for horses and equitation would chose a career in the cavalry in the interbellum days between World War I and II.

It was no surprise that Gustaf Nyblaeus followed his father by becoming a cavalry officer in the 1920s. From 1929 to 1931 he spent his time at Sweden's world-famous cavalry school of Strömsholm which was founded by King Gustav Adolf as a stud at the beginning of the 17th century. From 1868 it served as the centre of the Swedish cavalry for one century and was also as a training centre for the Olympic equestrians.

During his time at Strömsholm young Nyblaeus got a thorough equestrian education being trained in all the Olympic disciplines as well as steeple chasing. Due to his talent and determination he did well in all, but he focused on jumping and three-day eventing when his career took an international turn at the beginning 1930s. Gustaf Nyblaeus made it on the Swedish team of jumpers which was invited to take part in the USA's most important indoor shows where Sweden's team won on a few occasions in 1933.

During his time at Strömsholm young Nyblaeus got a thorough equestrian education being trained in all the Olympic disciplines as well as steeple chasing. Due to his talent and determination he did well in all, but he focused on jumping and three-day eventing when his career took an international turn at the beginning 1930s. Gustaf Nyblaeus made it on the Swedish team of jumpers which was invited to take part in the USA's most important indoor shows where Sweden's team won on a few occasions in 1933.

In 1934 the 27-year-old was entrusted with a petite high strung Swedish thoroughbred called Monaster xx i to prepare him for the 1936 Olympic eventing competition. Nyblaeus succeeded in this goal and was on the Swedish eventing team in which Henri St. Cyr also rode. The latter would later become the 1952 and 1956 double Olympic champion in dressage.

“My father's horse was too inexperienced for the Olympic Games and nervous in dressage,” Nyblaeus' son Gustaf Junior told Eurodressage.

Inexperience was not the reason for Monaster xx becoming one of three unfortunate eventing horses that lost their lives on the extremely demanding cross country in 1936 though. While finishing the steeple chase in the best time of the day the thoroughbred broke down and ruptured all tendons in the right front leg which, according to Dr. Rau in his book about these Olympic riding events “was predestined for such kind of injury due to his obvious thin and long fetlocks.”

Nyblaeus had also qualified for the jumping event, but declined to start. Although he did not have a too encouraging Olympic start in Berlin, nobody knew that it was the beginning of a remarkable Olympic career.

Nyblaeus had also qualified for the jumping event, but declined to start. Although he did not have a too encouraging Olympic start in Berlin, nobody knew that it was the beginning of a remarkable Olympic career.

Drifting to Dressage

While it is now rather exceptional that a rider competes internationally in two disciplines, it was not that unusual before World War II as the cavalry schools provided horses and a training that allowed such a mixed equestrian career. Gustaf Nyblaeus proved his versatility already before the war by becoming 1937 Nordic champion with the Swedish dressage team in in Helsink and 1939 Nordic Champion in Gothenburg with the eventing-team. He won the individual jumping championships at the same event on the appropriately named Sauteur.

In the first Olympic Games after the war he acted as the chef d'equipe of the Swedish jumping team. However another function made an impact on him, that influenced him and dressage for the next 40 years to come. Gustaf Nyblaeus acted as the secretary of the man whom he might have admired as a small boy in Stockholm in 1912: Count Carl Bonde, the first Olympic champion in dressage ever. Bonde judged dressage at the 1948 Olympics in London and Nyblaeus, at his early 40s, got infected by judging fever. It never left him again, even though he almost made the Swedish dressage team four years later as the rider of Safari, a horse which was also good over fences.

From 1953 to 1959 Nyblaeus became chief at Strömsholm and in this function he acted as the chef d'equipe of all three Swedish teams in the 1956 Olympic Games that returned to Stockholm due to the strict Australian quarantine regulations at that time. Three out of 6 possible Olympic gold medals went to “his” riders, so it was a major success.

From 1953 to 1959 Nyblaeus became chief at Strömsholm and in this function he acted as the chef d'equipe of all three Swedish teams in the 1956 Olympic Games that returned to Stockholm due to the strict Australian quarantine regulations at that time. Three out of 6 possible Olympic gold medals went to “his” riders, so it was a major success.

After he left Strömsholm Nyblaeus switched to the profession for which he became utterly respected and remembered long after his death: an irreplaceable authority in dressage judging. Because of his numerous successes as a rider, trainer and chef d'equipe Gustaf Nyblaeus had already made himself a name on the international scene for being a uniquely versatile, objective and skilful horseman. It surprised nobody that he was chosen to judge eventing dressage at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome.

Rome was the beginning of a career as an FEI-judge which spanned more than two decades. Between 1960 and 1980 Gustaf Nyblaeus didn't miss any international championships as a judge, being the president of the ground jury on several occasions. At the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo he even judged eventing dressage as well as dressage itself. “It must have been quite an exhausting task for my father,” Nyblaeus Jr. remarked.

The Core of Dressage

With his strict approach and incorruptible eye his father did something indispensable in dressage: he showed riders and trainers which way of riding was appreciated by the judges and which way they rejected.

With his strict approach and incorruptible eye his father did something indispensable in dressage: he showed riders and trainers which way of riding was appreciated by the judges and which way they rejected.

For Nyblaeus dressage competitions had only one aim: FEI article 419 which constitutes judges as the guardians of equestrian art. What judges understood under “equestrian art” though was a different kettle of fish during those days compared to our times. Nationalism in judging was as much a problem until after the war because each judge kept the principles of their own national riding approaches in the back of their mind.

Both problems could not be exterminated in the history of Olympic dressage until it peaked negatively again at the 1956 Olympic Games in Stockholm, where nationalistic judging was at its worst and probably prevented a female rider to become the first female champion! More so it endangered the Olympic spot for dressage for the first time. Oviously this is an ever-enduring struggle but back then it led to the fact that there was only an individual competition in 1960.

Nyblaeus was aware that the future of dressage was strongly dependent on the judges' credibility and that general standards for uniform judging were in dire need. The FEI dressage regulations had been existant since 1929 and they were a help, but left too much range for personal interpretation.

When Gustaf Nyblaeus was elected on the board of the FEI (where he remained until 1981) one year after having judged his second Olympic Games in 1964 he considered it his main task to improve judging world wide.

When Gustaf Nyblaeus was elected on the board of the FEI (where he remained until 1981) one year after having judged his second Olympic Games in 1964 he considered it his main task to improve judging world wide.

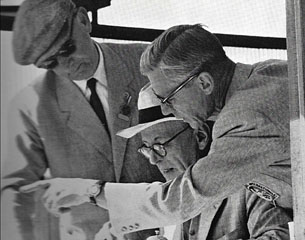

“I think that the education of judges has existed before my father, but it was mostly on a national level. What he did, as far as I remember, was to gather international judges together at meetings. There they could discuss the proper way to execute the movements in dressage and to come to an agreement so that tests would be judged in a more uniform way, regardless of the nationality of the judge. I myself was taking part as a rider in such a meeting that took place in Strömsholm in the early 70s. That way my father introduced mandatory judges' training in Sweden as well as on an international level," Nyblaeus Jr. reminisced.

It is probably thanks to his father that nowadays judges all over the world apply (more or less) the same standard when judging international dressage competitions. Judges' training got the importance it deserves as they realized the huge responsibility judges have for the result of each competition and the signals they give with it to the future and preservation of the sport.

Setting the Standard

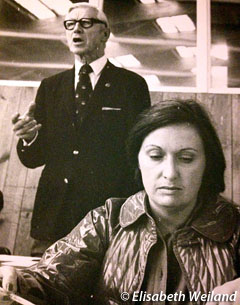

Because of his incomparable experience and skills Nyblaeus became a highly frequented authority during his career as a judge, giving seminars and clinics all over the world in his attempt to improve judging so that it could do justice to the aim of preserving equestrian art: “In 1975 my father visited 15 countries on all 5 continents to give clinics and seminars," said Gustaf Junior.

When it was undoubtedly the Swede's aim to secure the high level of dressage training according to the classical principles by rewarding those riders with proper scores, another aim was to spread dressage beyond its heartland, Europe. He became aware that to develop dressage in countries where the sport has no tradition it was necessary to offer riders not only help, but a possibility to compete even when the international championships (still) seemed out of reach.

When it was undoubtedly the Swede's aim to secure the high level of dressage training according to the classical principles by rewarding those riders with proper scores, another aim was to spread dressage beyond its heartland, Europe. He became aware that to develop dressage in countries where the sport has no tradition it was necessary to offer riders not only help, but a possibility to compete even when the international championships (still) seemed out of reach.

Nyblaeus initiated a series which became known as the “FEI World Dressage Challenge” and offered international competitions on different levels up to Prix St. Georges. Instated in 1982 the series had international judges conduct clinics on the one hand and judge classes to give riders an idea what they were looking for internationally on the other. In hindsight one can say that the series became a huge success: The interest for dressage increased all over the world and some countries, which first sent riders to these classes, are now regularly taking part in international championships up to the Olympic Games.

While Gustaf Nyblaeus was in fact interested in increasing the interest in dressage world wide, he wasn't prepared to do that at all costs. When in 1981 Dr. Reiner Klimke approached the FEI with the idea of establishing a World Cup for dressage, according to the already successfully existing format for jumping, Nyblaeus rejected the idea in his last year as FEI dressage committee’s chairman (which he took up in 1969).

Through a World Cup system Nyblaeus feared negative consequences for the sport, which actually did happen later on. Prof. Dr. Heinz Meyer, former editor-in-chief of Germany's leading equestrian magazine St. Georg, commented in his reference book “Rollkur” that Nyblaeus' objections had been put aside by many because the “commercial temptations had been too big, the more so as they could be combined with the argument to secure an Olympic spot for dressage.”

Through a World Cup system Nyblaeus feared negative consequences for the sport, which actually did happen later on. Prof. Dr. Heinz Meyer, former editor-in-chief of Germany's leading equestrian magazine St. Georg, commented in his reference book “Rollkur” that Nyblaeus' objections had been put aside by many because the “commercial temptations had been too big, the more so as they could be combined with the argument to secure an Olympic spot for dressage.”

Gustaf Nyblaeus' successor, the late Swiss O-judge Wolfgang Niggli, finally agreed on creating a dressage World Cup in 1983. A decision which his predecessor criticised by pointing out that even dressage enthusiasts seemed to have forgotten the aim of international dressage competitions like the FEI had phrased in (the still valid) article 419 of its regulations.

"Judging in Favour of Justice and Truth"

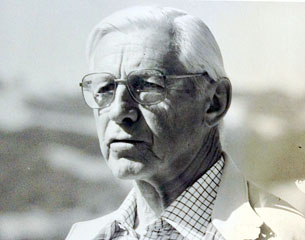

It goes without saying that when somebody stays at the top of his game for such a long time, it is not always plain sailing. The more so as Nyblaeus never wavered in the beliefs and principles, as FEI Dressage Committee Chair and as judge. His key motto always remained: to judge what he saw on a particular day, regardless of former successes or the high profile name of a rider.

“My father simply judged after his convictions and sticked to them. His role model had been Dr. Gustav Rau who said something at Aachen in 1954 that became the leitmotif of my father when judging: 'Judging means overcoming oneself in favour of justice and truth'.”

While surely one or the other rider wasn't too happy with the assessment he got -- typical for dressage -- Nyblaeus is said to have always been free to offer advice to any rider. Several international riders of the 1970s, among them Olympic champion Christine Stückelberger, confirmed to Eurodressage that Nyblaeus never refused advice when asked and that his advice had been sound and helped riders to improve.

Ulla Hakanson, Sweden's dressage flagship in the 1970s, reported to Eurodressage that “Gustaf was known as a very good judge, strict and with a true conviction. He was very active in my own country, but also regarding the international judges' training.”

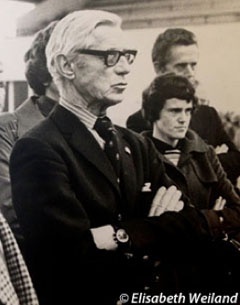

Even though Nyblaeus authority was never touched or questioned, one incident made his name known beyond the equestrian community. At the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich Gustaf Nyblaeus had been chosen to be “chief judge” and his judgement of Germany's “national hero” Dr. Josef Neckermann caused a stir; not only amongst spectators, but also in the German yellow press which printed an article with the title “Swede deceived Neckermann.” It is a fact that in the Grand Prix Nyblaeus awarded Neckermann and his Holsteiner mare Venetia (by Anblick xx) between 29 and 41 points less than his colleagues did. Given that Germany, in its own country, lost the coveted team gold to the Soviet Union by just 12 points Nyblaeus' score became the focus of criticism and was raised to a matter of national interest.

Even though Nyblaeus authority was never touched or questioned, one incident made his name known beyond the equestrian community. At the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich Gustaf Nyblaeus had been chosen to be “chief judge” and his judgement of Germany's “national hero” Dr. Josef Neckermann caused a stir; not only amongst spectators, but also in the German yellow press which printed an article with the title “Swede deceived Neckermann.” It is a fact that in the Grand Prix Nyblaeus awarded Neckermann and his Holsteiner mare Venetia (by Anblick xx) between 29 and 41 points less than his colleagues did. Given that Germany, in its own country, lost the coveted team gold to the Soviet Union by just 12 points Nyblaeus' score became the focus of criticism and was raised to a matter of national interest.

“My father thought that Neckermann's horse was tense and not quite even in her gaits which is a basic fault. Dr. Neckermann himself did not object,” Nyblaeus junior reported. What the German press of course did not mention was that the German judge, 1936 double Olympic champion Col. Heinz Pollay, favoured all German riders and downgraded the best Russian rider, Dr. Elena Petushkova on Pepel, significantly compared to his colleagues.

Josef Neckermann wrote in his autobiography “Im starken Trab” that as a rider he was surprised that one judge differed so much from the others, but that he was also embarrassed by the reactions of the German press because he never had doubted Nyblaeus' integrity for a moment. Josef Neckermann's daughter Evi Pracht confirmed to Eurodressage that “my father had in fact been surprised that one judge deviated from the others so much, but for him it was of greater importance that he had won two medals on Venetia. The mare was diligent and reliable, but no four-legged high flyer. Moreover my father had broken a vertebrae earlier that year in a fall and rode with a brace, so his delight about the individual bronze-medal was the greater.”

Double Duties

Munich was certainly a memorable part of Nybleaus' career, but another indelible one happened during the pre-Olympic equestrian competitions in Mexico-City in 1967. He was invited to judge dressage, flew over and found out that nobody was awaiting him and no hotel-room was booked. It turned out that dressage was cancelled because not enough riders had applied. Nobody had informed Nyblaeus that he was not needed.

“Since he did not want to make the long journey back after just a few days, my father managed to find himself a mission there. After he had found out that there was only one judge planned instead two as internationally required for the water-jump during the jumping competition he got himself the job through the organisation.”

Thirteen years later Gustaf Nyblaeus had the doubtful honour to judge dressage the 1980 boycott Olympic Games in Moscow. He would also get another unforeseen function there. The Technical Delegate for cross country, Swiss Olympian Anton Bühler, resigned the day before the event out of fear for serious accidents as the starters' field partly consisted of inexperienced international riders because of the boycott. Gustaf Nyblaeus together with the FEI's Fritz Widmer took over these responsibilities and luckily none of Bühler's fears realised in the end.

Thirteen years later Gustaf Nyblaeus had the doubtful honour to judge dressage the 1980 boycott Olympic Games in Moscow. He would also get another unforeseen function there. The Technical Delegate for cross country, Swiss Olympian Anton Bühler, resigned the day before the event out of fear for serious accidents as the starters' field partly consisted of inexperienced international riders because of the boycott. Gustaf Nyblaeus together with the FEI's Fritz Widmer took over these responsibilities and luckily none of Bühler's fears realised in the end.

Even though Gustaf Nyblaeus retired from being the chairman of the FEI dressage committee in 1981, he continued judging until 1984. His very last competition was the US Championships. At age 76 he also held his last clinic in North Carolina the same year.

One of the greatest and most versatile horsemen of the 20th century, known for his talent to communicate with a great sense of humour, passed away in 1988.

Nyblaeus' enormous impact on the development and popularity of dressage all over the world is undoubted and mentioned by all those who were fortunate to have him in their life. Unfortunately, if the name Nyblaeus doesn't ring a bell for the younger competitors of our days it reflects a bit the times in which equestrians are living: too often forgetting or ignoring a past on which the future should be based.

Unfortunately this mental attitude is also reflected in the sport of dressage in which aspects now dominate which Nyblaeus' sensed and feared and which he tried to fend off as long as possible: commercialism and publicity at all costs! He feared certain changes would be to the detriment of the horse and what he tried to preserve: classical equitation. Gustaf Nyblaeus was well aware of what he faced at a wall in Strömsholm for many years: “True horsmanship doesn't age. Where art stops, violence begins.”

by Silke Rottermann for Eurodressage - Photos © Private archive - Elisabeth Weiland

References

Interviews with Gustaf Nyblaeus junior on 29th October 2014 and 29th December 2014.

Interview with Christine Stückelberger on 11th September 2014.

Interview with Eva-Maria Pracht on 9th January 2015.

Max E. Ammann, The FEI Championships, Lausanne 2007, page 246 / 247.

Col. Christian Carde, M. Debure, Le dressage et la compétition, Paris 2014, page 61.

Angelika Frömming, Bilder und Fakten zur Entwicklung der Ausbildung von Reiter und Pferd, Warendorf 2011, page 139.

Sylvia Loch, Dressur-Die Kunst der klassischen Reitweise, Stuttgart 2010, page 191-192.

Prof. Dr. Heinz Meyer, Rollkur-Die Überzäumung des Pferdes, Schondorf 2008, page 582-585.

Josef Neckermann, Im starken Trab, Warendorf 1992, page 229-232.

Gustav Rau, Die Reitkunst der Welt an den Olympischen Spielen 1936, Berlin 1937, page 247 and 282.

Albert Stecken: “Richten und Richtverfahren”, in: Dr. R. Klimke, A. Stecken, A. Müller, München 1972-Olympische Reiterspiele, Münster 1972, page 104-108.