-- text © Silke Rottermann for Eurodressage

With the five Olympic Rings hanging at the iconic Eiffel Tower in Paris since June 2024, the clock is ticking down fast to the opening of the next Olympic Summer Games which return to a historic place this year.

Exactly one century ago France’s capital hosted the Olympic Games in 1924 and with them the dream of the Paris born baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern age Olympic Games, came true. After little public recognition of the competitions during the very first Paris Games in 1900, the baron aimed to present a different picture and got it before his retirement from the IOC.

The 1924 summer Olympics in Paris, which spanned a remarkable long period between 4 May and 27 July, were in many aspects a „turning point in sports history“ as sports historian Michael Attali mentioned in an article published on the ZDF website. The same could be said for the equestrian events of that long gone Games. For the first time they were held under the auspice of the FEI which was founded just three years earlier in 1921.

Memorable Games

In Olympic history those 1924 Games in France’s capital will forever be remembered for Finland’s ‚miracle runner‘ Paavo Nurmi, for American multi medalling swimmer Johnny Weissmüller who later became world-famous as „Tarzan“ and they are immortalized in the 1981 Golden Globe winning movie „Chariots of Fire“.

Of the participants of this 8th Olympic Games of the New Age about 3000 were male and only 135 female. Equitation was still 28 years away from allowing women to compete with men in dressage, let alone in the other two equestrian disciplines. So there were 111 riders - military officers and so-called gentleman-riders - who took part in the three equestrian disciplines which we still know today.

What sounds a bit modest nowadays, was a new record back then and a significant progress from 87 riders at the 1920 Games in Antwerp, which suffered from the direct consequences of the just finished World War I. The dates were also announced very late so few athletes were ready and prepared.

First Olympics under the FEI Rules

After the 1920 Games in Antwerp and prior to the Paris 1924 it had become clear that it was more than necessary to organize the ever-growing sports in common international associations and create universal rules to be applied at future Olympic Games.

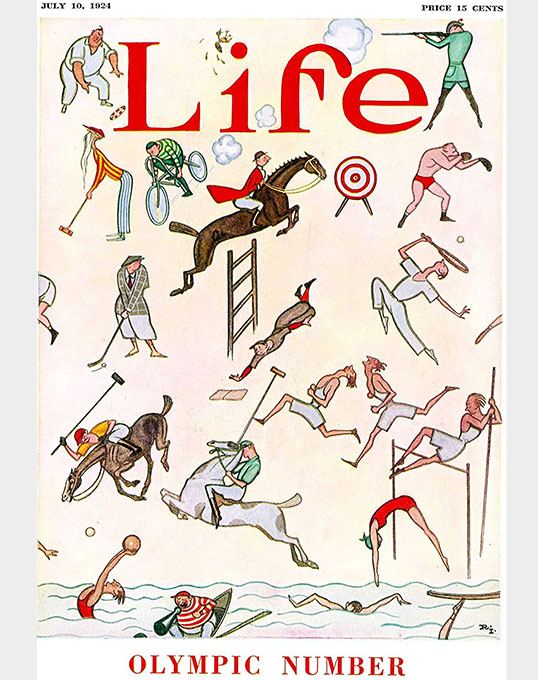

attention far beyond the border of the

country which hosted them. American LIFE magazine

dedicated a whole number to Paris 1924.

Six months later the FEI was founded and the FEI determined the three disciplines of dressage, jumping and eventing to be the ones for future Olympic Games (and have remained ever since). They also decided that the dressage program of Antwerp 1920 should also be the one for Paris 1924.

The same year also a general rule-book was published, though it took until 1929 to get a specific one for dressage competitions

So the dressage riders, all from Europe at that time, knew what to expect at the Paris Games they travelled to in July 1924. At that time the Games were already running for over two months. What they perhaps did not expect were the challenges the organization on-site would hold for them in this hot July week during which 24 horses from 9 different nations were in Paris to decide their new Olympic dressage champion.

A Long Way to Centre Stage

It has become common practice to stable the Olympic horses close to the place where the competitions take place, so that they either had just a stone's throw to walk to get to the arena or a rather short transport by trailer to get there. With some very rare exceptions concerning eventing this concept has been practiced since at least 1932.

central Paris was the 1924 Olympic stadium in

which also the dressage was held.

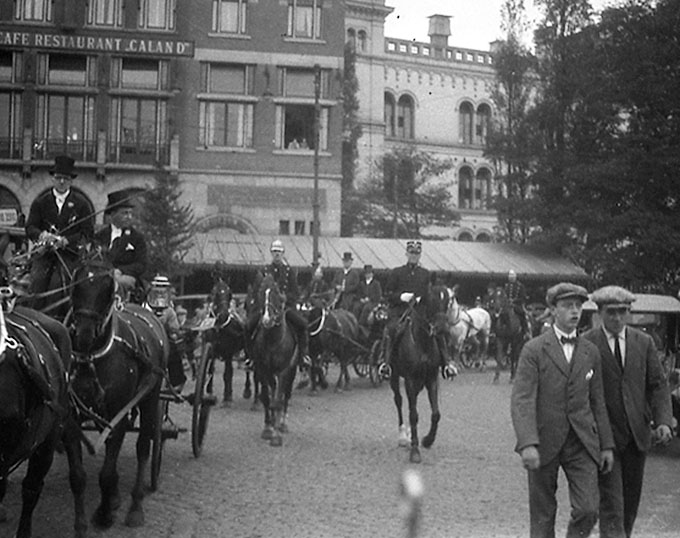

Instead the Olympic dressage horses were spread out in stables all over Paris and their riders had to access the Bois de Bologne to train their horses. For most horses getting to the Olympic stadium meant a walk of over two hours through Paris’ traffic which was notorious even 100 years ago.

Those who could afford and organize it, rented transporters to get their valuable horses from the stables to the training location and to the competition stadium.

The time-consuming and certainly stressful way of getting the horses from A to B was not the only inconvenience back then. Even 24 hours before the Olympic dressage competition was about to start, the competitors did not know when the first rider would enter the arena or who it would be. However, as some riders fought in World War I on horse-back just a few years earlier, things like these were probably less of a hassle than we consider it nowadays.

Also the spectators had to be patient as the starter lists were only available 30 minutes after the Olympic dressage competition was underway on 25 July 1924.

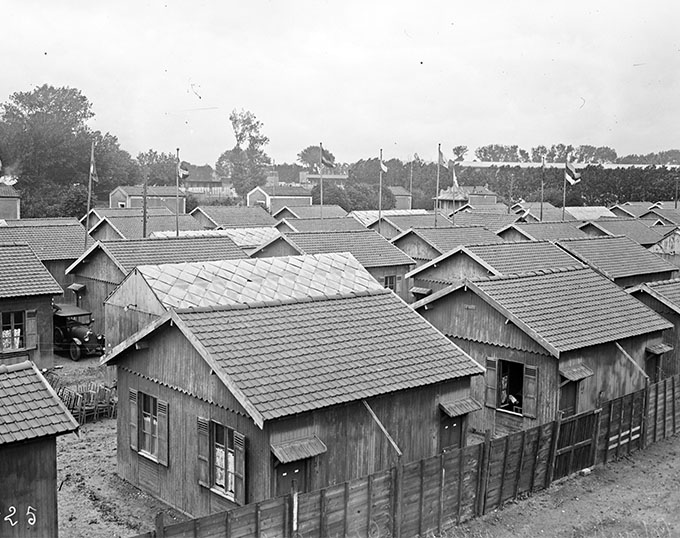

of the Olympic village was born in Paris 1924

Imagine there are the Olympics in Dressage and Nobody Watches Them!

With the exception of the cross-country phases all equestrian competitions took place in the Stade de Colombes, where hockey will take place for the 2024 Olympics.

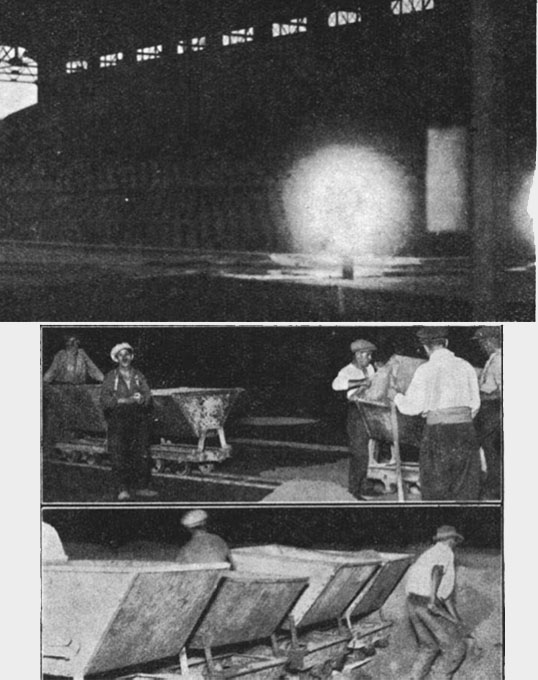

After the gymnasts finished their competitions, in the night from 20 to 21 July 1924 a major operation was undertaken. One thousand five hundred cubic-meters of sand were transported in small lorries to the Olympic stadium and expertly distributed under strong lights to shape the dressage arena which was used first for eventing dressage.

workers started to install a dressage arena

in the Olympic Stadium and had to work all

through the night

The term "arena familiarization" did not yet exist and it was explicitly forbidden to use the arena in the Olympic stadium before the competition. To allocate the dressage competition of the 1924 Games to Stade de Colombes was certainly well intentioned, but as Germany’s legendary hippologist Gustav Rau mentioned in his book Olympische Reiterwettkämpfe, "it was the worst possible choice for such an event.“

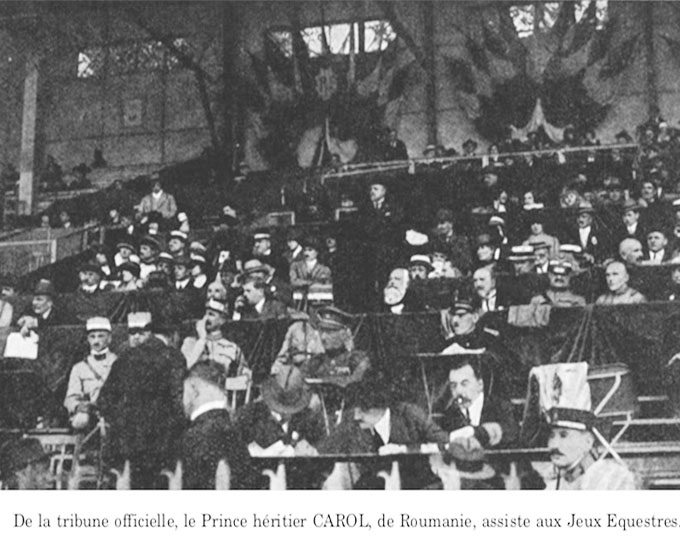

With public transport in its very infancy and the stadium far away from the town centre, just a bit more than 600 paying spectators were practically lost in the huge stadium with a capacity of 45,000 spectators. To this tiny number of paying spectators was eclipsed by the much larger delegation of officials, team members and their entourage as well as accredited journalists. In the end less than 2,000 spectators were in the huge stadium and followed Olympic dressage. A disappointing result regarding public attention. Dr. Rau expressed his discontent by stating that "a better number would certainly have been achieved by allocating dressage to the Polo Club in the Bois de Bologne."

The poor number of spectators in dressage did not go unnoticed. While previous Olympic Games were almost a secret affair outside the city which hosted them, and press coverage a far cry from the modern media age, the Paris 1924 Olympics can be called the first with proper public recognition, also abroad, and therefore became a stepping stone for the growing Olympic movement.

The Olympic Sized Dressage Arena is Born

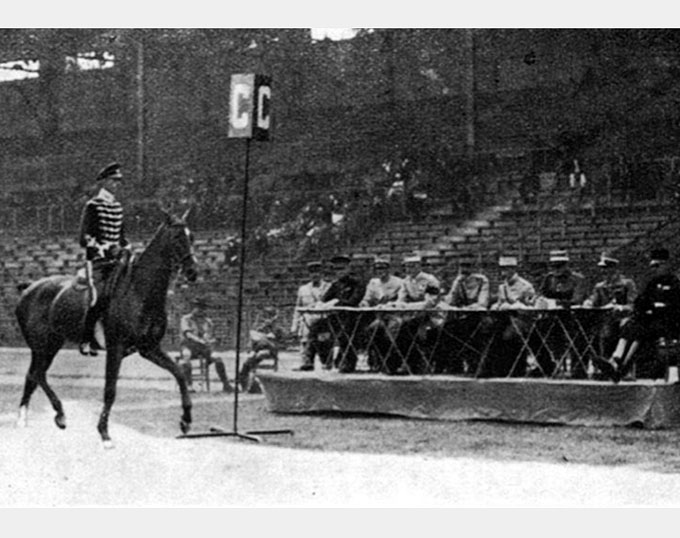

When the day of dressage competition finally came, for the first time in Olympic equestrian history horses and riders had to perform in the dressage arena which we know today, a rectangle shaped arena measuring 20 x 60 meters and marked with the well known letters.

a long table at the short side at C which

was not fenced. Mark the post with the letter C

The short side at C, where the judges’ table was positioned, was not entirely fenced and the letter C was marked by a several meters high steel pillar, which was dangerously close to the first track which the horses used. All arena letters were on these high pillars alongside the arena. The arena itself was located in the middle of the Olympic stadium and was beautifully decorated by high white fences and little trees in between them.

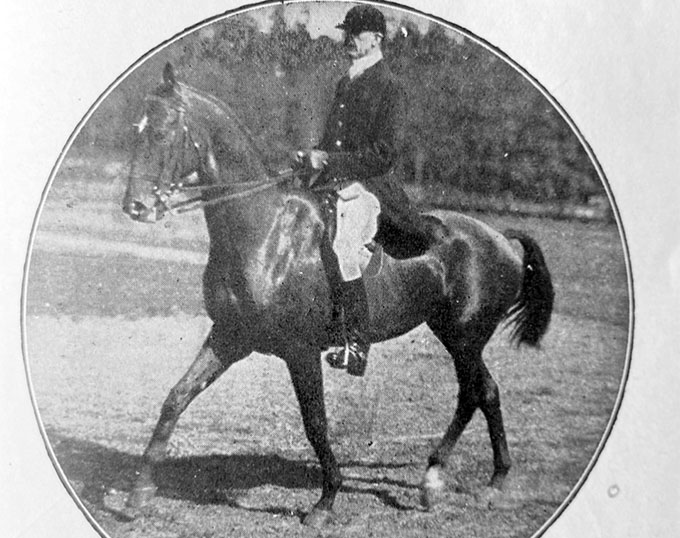

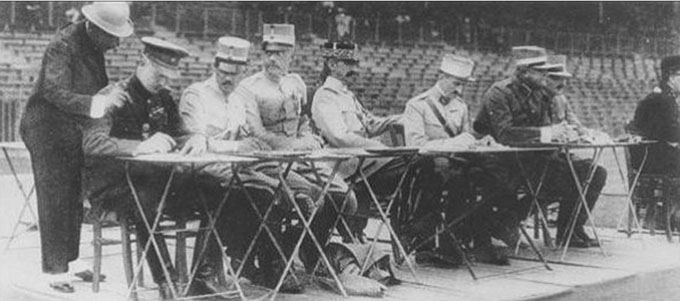

The president of the ground jury was General Detroyat from France, while Major de Trannoy from Belgium, Colonel Favre from Switzerland, Lieutenant Colonel van Essen from Sweden, and Jonckher van Ufford were the other four judges. Their countries all had starters in the Paris dressage field of 24 combinations, contesting only for individual medals. Although five of these countries fielded three or even (= the maximum allowed) four riders, no Olympic team competition was on the schedule. This would first be the case four years later in 1928 in Amsterdam with Germany as the gold medal winner.

Of all the horses in Paris only the Swedish bred Sabel had competed in Antwerp 1920 under the Olympic rings (with the same outcome there as in Paris). The age span of the horses in Paris was between 6 and 14, with the average age being approximately 9 years.

The Required Test

their Olympic dressage mounts through Paris

to the Olympic Stadium.

For some this meant more

than 2 hours „warming up“ through central Paris traffic.

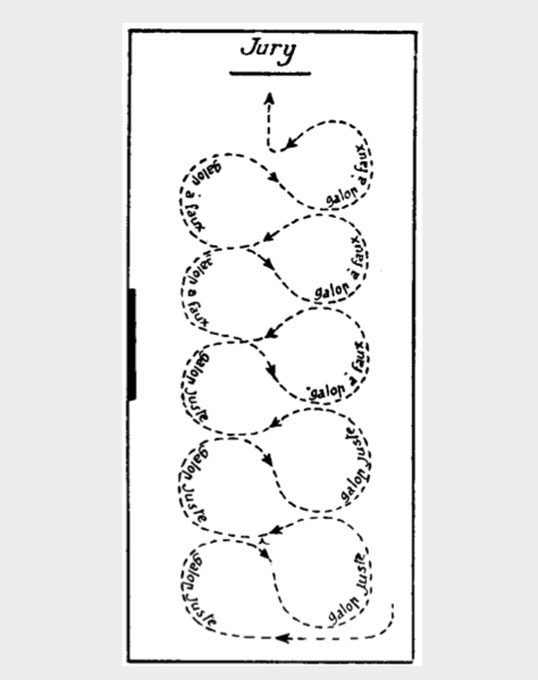

The language back then did not speak of collected movements, but of „short“ ones in opposition to extended ones. Movements like turn on the haunches in walk, counter canter and single flying changes while changing the rein within a circle on both leads, 5 looped serpentines in canter with flying changes after every loop, flying changes up to 16 one-times, zig-zag half passes in trot and canter as well as canter depart from the rein-back still were a level way beyond what a simple army horse was able to perform. Probably to check the balance of the horses the canter tour was asked to be performed 2 meters away from the first track.

but required several tricky movements

like these loops with constant flying changes.

The FEI had determined beforehand that after every ride the president of the ground jury had to ask for the protocols of his 4 fellow judges and to compare these. In case of judges differing too much from each other they had to explain themselves to the president. But what was considered a big difference and if there were cases in which the explanations were required, is not reported in any source available to this author.

Nowadays we are used to see all the action in many coloured and high resolution photos which catch every little detail, sometimes to the chagrin of the riders. One hundred years ago photography was a universe away from today. Still it is astonishing how little photo material is available from the 1924 dressage competition and apart from little journalistic interest, a reason might be that the spectators and the photographers were at least 60 metres away from the dressage arena which appeared a bit lost in the huge Stade de Colombes. This probably made it not easy to catch horses and riders in action or observe the rides in all their details, except one was one of the five judges.

A "Race" for Olympic Glory: Time Limit to Ride Test

In Paris 1924 and for a long time after, to the downfall of some favourites who couldn’t stick to it, there was a time-limit in which horse and rider had to execute their program. Time was ticking away from the moment a rider had greeted the judges.

For whatever reason, perhaps because for the first time the bigger arena 20 x 60 m arena was used, the time was wrongly calculated for the Paris Olympics. It soon became apparent that the 10:30 min time limit was way too tight after the first riders who executed the program correctly collected an amount of „time faults“ which left them with no chance to place highly. "The first riders paid the price for the others that followed," Gustav Rau hit the nail in his book Olympische Reiterwettkämpfe.

finished in 15th place for the host nation

Many of us still have the riding instructor’s advice ringing in our ears "Do not cut the corners!" but to prevent the notorious time faults, it was exactly what needed to be done on 25 July 1924 in Paris. As a result the rides which followed later ended up racing through the program than anything else. Once it became obvious the time allowed was not sufficient to show the required program, riders adjusted to it. They significantly cut the corners, stayed not two, but up to four meters away from the first track in canter, shortened the rein-back and rode the collected movements in a faster tempo to somehow keep the time.

What in principle should be a quiet calm affair truly became a race against the clock to uphold any medal chances.

Sweden Continued Its Domination

Since the official inception of the three equestrian disciplines at the 1912 Olympics the country of Sweden dominated them.

In 1924 CDI shows were non-existent and the possibilities to compete internationally comparatively zero. So it was hard to predict the outcome of the Olympic Games. As Sweden had dominated the previous two Games and on top of that had a medal winning combination of Antwerp on their team, they were certainly hot candidates for the podium.

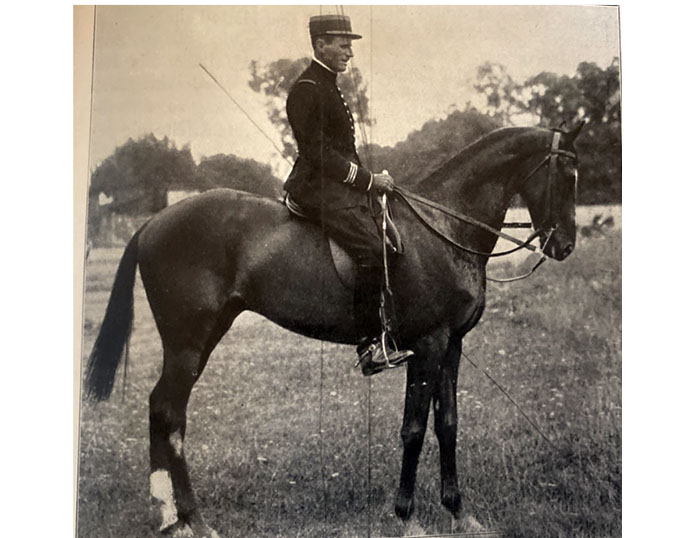

'ring' behind the Olympic Stadium

On 25 July 1924 Paris saw a head-to-head-duel between the 56-year old retired Swedish general Ernst von Linder and 1920 silver medalist, 36-year-old officer Bertil Sandström. It might be surprising to hear in our times, but von Linder was an accomplished horseman who had raced 80 times and won 20 races until 1918 and had furthermore successfully competed in all three Olympic disciplines. In Paris he rode the 11-year old very refined looking Trakehner gelding Piccolomini (by Fischerknabe x Moeros) who first sold at the so-called East Prussian auction in Berlin as a 4-year-old and later as an advanced dressage horse to Sweden via a renowned German horse dealer.

In his description Dr. Rau called the Trakehner "the type the world market is looking for" and described his Paris performance as "a masterpiece" in which the rider presented the horse with "greatest finesse."

Perhaps surprisingly Von Linder got the highest scores from the French (283) and Dutch (278) judge, with the Swedish (277), the Swiss (272) and Belgian (272) close behind. The relatively similar marks of the jury proved their unison about the presentation of who would become the new Olympic champion in the end.

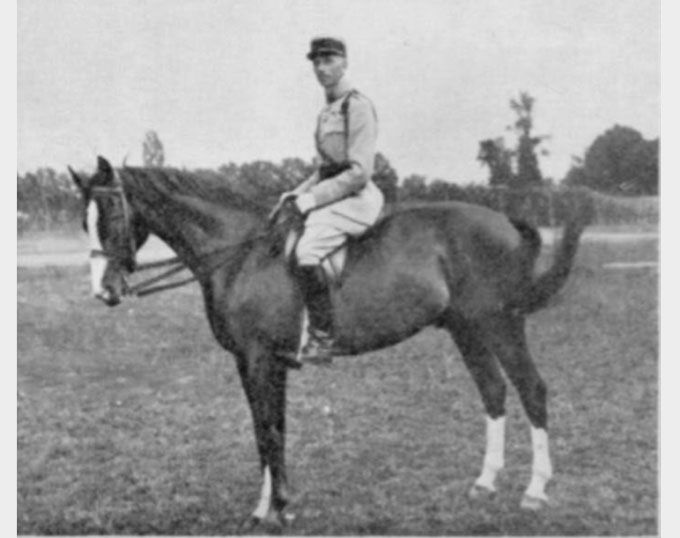

Just a whisker behind were Bertil Sandström and Sabel, who again took the silver medal.

in Sweden before the 1924 Olympics, was the

outstanding dressage horse of his time

and certainly ahead of it.

Rau called the monumental Swedish bred, noble looking liver chestnut (by the SWB Sans Reproche- x Belisair) "close to perfection" and highlighted his graceful way of going and the effortless lightness in which he executed the program. It is reported that during his outstanding flying changes in series spontaneous applause burst from the tribune, certainly something very rare back in the day. Although Sabel stayed three points behind Piccolomini, the judges again were pretty close and differed a maximum of just 9 points (279 to 270), something which was not always the case with the lower placed horses.

Rau stressed that in Paris Piccolomini as well as Sabel showed themselves significantly improved compared to the past. From a modern day perspective and in comparison to other horses in Paris back then one can without a doubt say that both horses were quite ahead of their time regarding their refined looks. Piccolomini became the first German bred horse to take an Olympic gold medal in dressage, many more would follow in the 100 years after.

double Olympic silver medalist Sabel before

entering the Olympic Stadium in Paris.

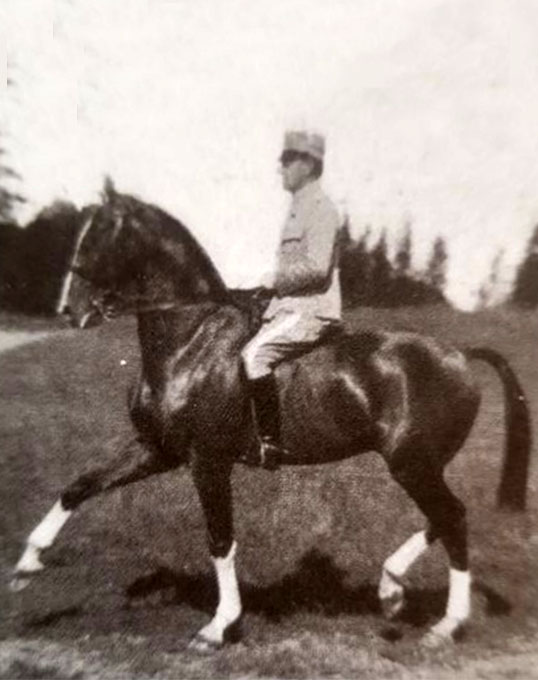

Lesage’s performance was outstanding in a way as the self-taught rider, who would later become écuyer en chef of the Cadre Noir, having picked up his knowledge from General L’Hotte’s book „Questions Equestres“ at home in Epernay. He was discovered less than a year before the Olympics by general Wattel, then chief rider at Saumur, when he was scouting for possible riders for the Olympic Games on home-soil. Impressed by Lesage’s talent, he entrusted him with the 12-year-old French thoroughbred Plumarol a mere 9 months before the Games. To then ride in the Olympics and get a bronze medal is no mean feat and speaks volumes of Lesage’s ability as a rider. Eight years later he would be crowned with the Olympic gold in Los Angeles.

The next two places were taken by the other two Swedish riders, cavalry captain Von Essen with the 10-year old East Prussian gelding Zobel and Viktor Ankacrona, who like quite many of the Swedish cavalry riders, had been trained in Saumur and Vienna besides their national school in Strömsholm. With the horse Corona he stayed just ahead of the best Czechoslovakian rider, cavalry captain Thiel with the German bred thoroughbred Ex.

Von der Weid was riding the stronger boned, but not inelegant 11-year-old Hungarian bred gelding Ulhard. He was described as a "very well trained, completely submissive horse" by Rau who added "that all would be perfect if it was obtained by even lighter aids." Von der Weid, who later became the head of the Swiss cavalry school in Berne, competed in two equestrian disciplines in Paris. Not medalling in dressage, the 30-year old took silver with the Swiss jumping team two days later. A remarkable performance even in times when specialization in one discipline was rather the exception than the norm.

Official Reports and Analyses

The Paris 1924 official report wrote that the overwhelming Swedish success in dressage confirmed the reliability of their method which was based on the cavalry schools of Hanover and Saumur (two methods which differed in some decisive points at that time). It continued by saying the Swedish horses were all forward, but very relaxed and attentive in a non-exaggerated elevation. The riders’ seat and position were described as supple, with well positioned legs, deep heels and forward.

Reading the very extensive and detailed descriptions Dr. Rau delivered in his book about the 1924 Olympic dressage rides one gets the impression that certain troubles had been existent with some riders then as are they now: overuse of spurs and hard punishing hands, swooshing tails, resistances in the mouth, lack of balance and straightness or faked collection where riders had taken short-cuts in the training.

The judges in Paris 1924 had their own equestrian education which was automatically influenced by the school of equitation they followed, just like the participating riders. Differences in the schools’ conceptions inevitably had an impact on how one rode or judged, with the German school requiring flexion and bend in half-passes, which the French didn’t, just to give you one example. With no universal criteria available, the judges in Paris 1924 base their judgment on their own training.

Only in 1929 a first specific dressage rule-book was published by the FEI after it commissioned a German (von Holzing-Berstett) and French (Decarpentry) general to write it. Their challenging task were to define what the movements should look like by bringing the best of both leading schools at that time, the German and the French, together in all-encompassing criteria. With this rule book the FEI made guiding principles to the FEI judges available.

Albeit Gustav Rau remarked about Paris 1924 that "the past three Olympic Games have proven that an international jury is able to make a decision which is on the whole correct."

The Olympic jury of 1924 consisted of five experienced horsemen and sat all next to each other at the short side at C

Now and Then

A century of Olympic dressage has passed since this 25 July 1924.

The sport has practically been turned upside down since then: The military has disappeared, women dominate the discipline, national riding styles have been galvanized, for a few decades now extravagantly moving horses are bred entirely for the purpose of dressage, the sport has spread all over the globe and has become big business.

One thing remains unchanged: The Olympic Games are still the ultimate goal.

-- by Silke Rottermann

References

- Max E. Amman, Buchers Geschichte des Pferdesports, Verlag C.J. Bucher, Luzern und Frankfurt am Main 1976.

- General Decarpentry / Jacques Perrier, Les Maitres Ecuyers du Manège de Saumur, Charles- Lavauzelle, 1993.

- FN Verlag (Hg.), Wir reiten für Deutschland, Warendorf 2013.

- Erich Glahn, Reitkunst am Scheideweg, Erich Hoffmann Verlag, Heidenheim 1956,

- Wolfgang M. Niggli, Dressage - A Guideline for Riders and Judges, J.A. Allen, London 2005.

- Alois Podhajsky, Reiten&Richten, Erfahrungen und Vorschläge, Nymphenburger Verlag, München o.A.

- Gustav Rau, Die Reiterkämpfe bei den Olympischen Spielen, Entwicklung und Stand der Reitkunst, Verlag von Schickhardt&Ebner, Stuttgart 1929.

- Schweizerischer Verband für Pferdesport / Max E. Ammann, 120 Jahre Pferdesport Schweiz, Bern 2020.

- https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll8/id/12649/rec/8

- https://labibliothequemondialeducheval.org/fr/p/235/les-sports-equestres-aux-jo-de-paris-1924.html

- https://labibliothequemondialeducheval.org/fr/p/174/jo-trop-long-trop-court.html

- https://olympics.com/de/olympic-games/paris-1924

- https://olympics.com/en/news/paris-1924-the-olympic-games-come-of-age

- https://olympics.com/ioc/news/paris-1924-and-pierre-de-coubertin-s-enduring-love-for-france

- https://sok.se/idrottare/idrottare/e/ernst-linder.html

- https://sok.se/idrottare/idrottare/w/wilhelm-von-essen.html

- https://sporthorse-data.com/pedigree/picolomini

- https://sporthorse-data.com/pedigree/sabel

- https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/sport/historie-1924-100-jahre-olympia-2024-paris-100.html

Photos © 1924 IOC Report (public domain) and Wikipedia (public domain) - FEI History Hub - SOK

Related Links

Scores: 1924 Olympic Games