This article is a continuation of The Essential Guide to the Canter Pirouette

Part I: Origin Steeped in Military Training

Part II: Pirouettes in Cavalry Manuals 1826 - 1912

Text by Angelika Fromming, edited by Silke Rottermann

Part III: The "Cantering" Hind Legs Prevailed

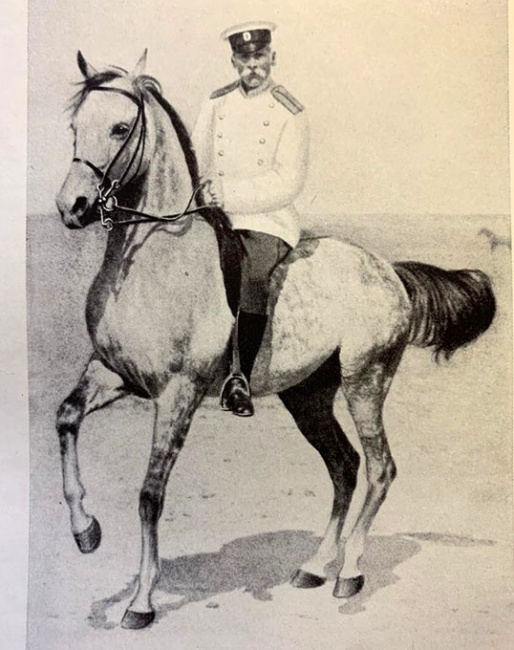

In a collection of informal hippological treatises, retired Colonel Peter Hartmuth Spohr (1828-1921) published the fourth part in the series "The Logic of Riding Art" in 1909: "The High School and its Relationship to Campaign Riding."

To perform the short turn in canter, it says "if you ride the smallest volte in redopp (...) you can do the short turn by letting the forehand make only two to three strides in it, while (...) only the outer rear foot does the downswing, the inner one, however, remains as a pivot on the ground. By making this turn ever shorter ... you will finally get to the point where the horse covers the volte in one swing, pivoting on the inner hind foot.”

Spohr emphasizes that he has performed the short turn with numerous horses in one swing.

Spohr suspects that this appearance of the whole pirouette may have been a “visual and emotional illusion” on the one hand. On the other hand, he sees an explanation in the fact that the horse "has already completed the first half of the circle by swinging the outer rear foot" and "now swings with the inner rear foot to complete the second half" and thereby swings with it for a brief moment all four feet in the air.

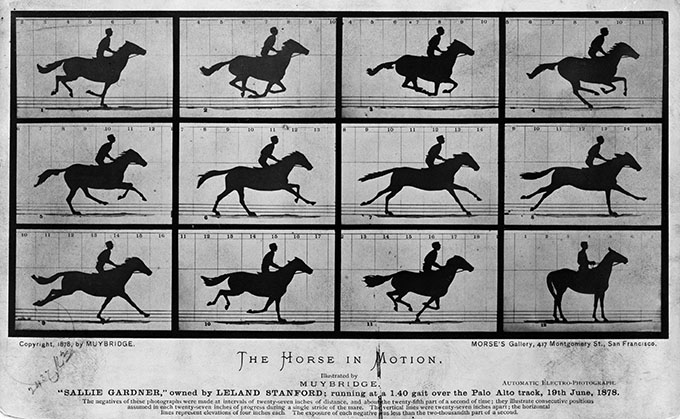

As proof of this assumption, Spohr cites the approx. 390 snapshots in the book "Les allures du cheval" from 1907 by the French lieutenant Fr. Gossart. Today we know that von Holleuffer unfortunately misrepresented the sequence of feet in his book "The training of the riding and carriage horse in the Pilars 1896".

Photographic Evidence

In the meantime, the findings of Edward Muybridge (1830-1904) have come to bear with numerous experts.

The photography as a documentary snapshot and the slow-motion recordings have led to the fact that since the end of the 1990s the clear three-beat is no longer required in the canter pirouette, but that only a canter stride has to be recognized. This phenomenon was already addressed in the 1930s and later in the 1960s, but until it was implemented, also in the regulations, it was still an eventful and discussion-rich path.

"A very Slow Canter that Does Not Die"

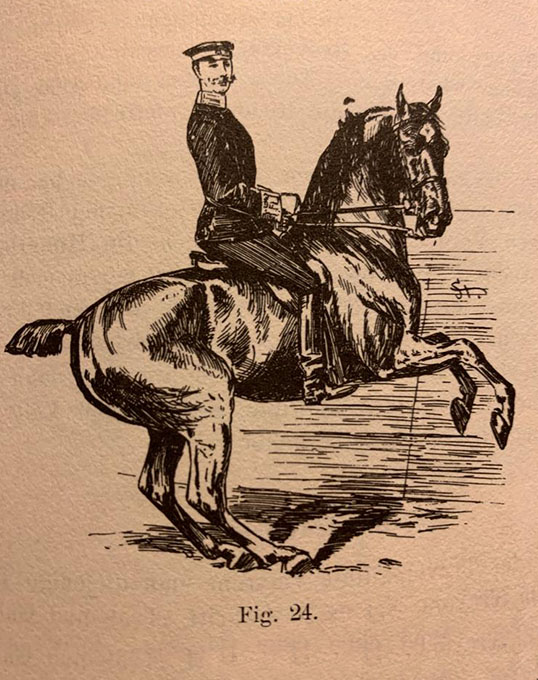

James Fillis (1834-1913) makes a fundamental statement in his book entitled “Principles of Dressage and Riding Art” (3rd edition 1905) about the sequence of movements of the canter pirouette: “In a canter pirouette, the hind legs should mark the canter on the spot, so to speak by raising and lowering themselves almost in the same place and turning, so that the shoulders, which form a circle around the center, remain in a straight line. The horse must never rest for a long time on one of its hind legs, as other authors probably demand, because in this case there would be no more canter."

From today's perspective, this is a very far-sighted statement. The endeavor to achieve “centered” canter pirouettes as possible can lead to the canter “dying out” so much that the horses no longer jump, but instead turn slightly rearing in obedience to the need.

Faverot De Kerbrech (1837-1905) gives the following advice for training the horse in the gallop pirouette in his book “The systematic training of the riding horse according to the last instructions of Francois Baucher” (1891/2008): "Make sure that the horse does not gain space forwards. On the other hand, however, prevent even the slightest hint of crawling.” And further: “Start the (canter) pirouette at walk and finish it with one or two canter jumps. Progressively you come to the point where you can finally ride half a pirouette at a canter. The horse just needs to be straight for this lesson. As soon as you are able to do a full pirouette at a canter, use your thighs as little as possible. Too much use of the legs leads to disorder, too short, nervous jumps, and the horse can no longer really come up in the canter. "

Faverot De Kerbrech now also demands that the horse make canter jumps in the canter pirouette and no longer just turn around a pivoting hind leg.

Coming Soon: Part IV - Three-or four-beat rhythm - an academic question?

Related Links

The Essential Guide to the Canter Pirouette - Part I: Origin Steeped in Military Training

The Essential Guide to the Canter Pirouette - Part II: Pirouettes in Cavalry Manuals 1826 - 1912

Angelika Fromming: Half a Century of Dressage

The History of the Shoulder-In

The Essential Guide to the Piaffe - Part I: The Piaffe is a Means to an End