This article is a continuation of The Essential Guide to the Canter Pirouette

Part I: Origin Steeped in Military Training

Part II: Pirouettes in Cavalry Manuals 1826 - 1912

Part III: The "Cantering" Hind Legs Prevailed

Text by Angelika Fromming, edited by Silke Rottermann

Three or four-beat rhythm - an academic question?

A comparison of the first and fourth edition of the „Gymnasium des Pferd“ by Gustav Steinbrecht (1808-1885) illustrates the history of the development of the canter pirouette, even within the various editions of a classic. The first three editions were published by Paul Plinzner (1852-1929), the fourth edition was then substantially revised by Colonel Hans-Sigismund von Heydebreck (1866-1935), especially with regard to the canter pirouette.

Plinzner

Before his death, Steinbrecht had written several essays on the training of horses. Plinzner summarized these in the text "Gymnasium des Pferd" with the addition of the chapters canter, piaffe, and passage.

In the first edition, written by Plinzner in 1886, it says about the execution of the canter pirouette: “These canter turns on the hindquarters are only to be carried out on the inner hind leg, which, as the feet become narrower, take on the load more and more alone, while the other three legs, in particular the outside hind leg, only has the role of repeatedly transferring the load to that inside hind leg in brief moments. "

Regarding the number of canter strides, Plinzner writes: “The number of strides the horse uses in a pirouette depends on its strength, agility and liveliness. The fewer there are, the nicer the pirouette and there are individual, excellently talented horses who, with increasing practice, come to the point of performing the pirouette in one jump or swing, while the number of those who can get around in two jumps is larger although this school is not every horse's business either."

Von Heydebreck

Von Heydebreck made a clear statement in his book “Die Deutsche Dressurprüfung”, published in 1929, with regard to the canter in a canter pirouette: “In a short turn, the horse should turn in the previous gait ... around a point that lies under the inner hind leg. However, both hind legs must remain in motion ... The pirouette is ridden according to exactly the same principles and is only a double short turn. "

In the 4th edition of the "Gymnasium der Pferde" from 1935, von Heydebreck now makes essential comments on Plinzner's remarks. For example, he writes about the beat in the canter pirouette: "As soon as the school canter develops, the three-beat becomes a four-beat, but this phenomenon must not be perceptible with the eye, otherwise it indicates that the movement has become sluggish".

This shows that Heydebeck allowed the findings of the “moment photography” to flow into his comments, which he also emphasized in the preface to the fourth edition of the “Gymnasium des Pferd” that he revised.

Heydebreck brings a new conceptual approach with regard to the speed and the number of canter strides in a well-executed pirouette: “The view represented here that the pirouette is the more beautiful the fewer jumps the horse uses for the whole turn does not correspond to the principles of the academic horsmanship. This evaluates the execution of all turns around the hindquarters not according to the speed and therefore not according to the number of jumps used, but according to whether the rhythm of the jumps and the balance during the turn remains exactly the same as immediately before. The horse must calmly continue cantering, so it must not be in a hurry or fall to the side, and after the turn has been completed, it must continue to canter on the track on which the turn was initiated. "

Von Heydebreck says here that the horse in the pirouette performs a canter in three beats for the eye, but in the moment photography it does a four beat.

Koch

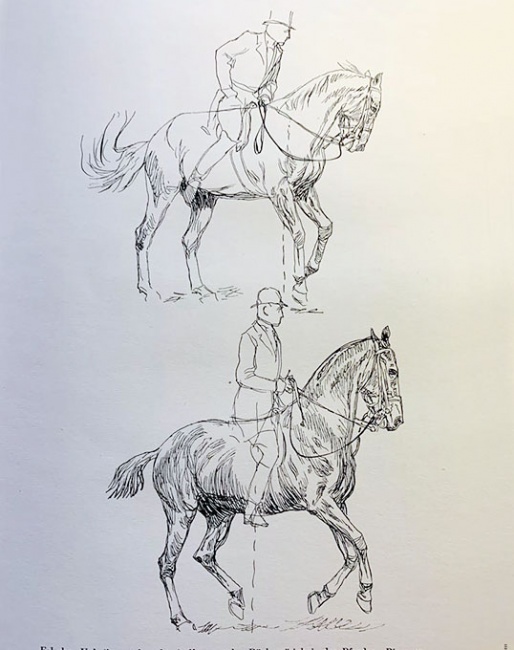

In 1928 a wonderfully illustrated book “Die Reitkunst im Bild” with numerous movement studies and explanations by Ludwig Koch (1866-1934) was published. There are also two representations of a canter pirouette, on the one hand as a continuous study of movement, on the other hand as a representation of the moment.

Koch sees problems with the description of the school canter. For him, the school canter also has to keep three tempi. “At the moment when four tempi are shown in the school canter, the canter is disturbed by any stiffness or tension and the momentum is lost. The school canter does not differ from the normal canter by the number of tempi, but only by more diligent, more rhythmic and more advanced jumps. When cantering in four tempi, that is, with four audible hoofbeats, it is a dissolved canter that is neither rhythmic nor diligent. "

He goes on to say: "The pirouette consists of four canter jumps with the hind legs as the center (...). The canter stride in the pirouette must not differ in any way from the school canter, the horse must not "stick" with the hind legs, but must push off with the hind legs as decidedly as when cantering forward, that means the canter must also be lively in the pirouette and must not be restrained.“

Stensbeck

Oskar Maria Stensbeck (1865-1932) says in his 1931 book “Riding” about the execution of half or full canter pirouettes: “Of course you have to slow the horse down on the hindquarters when executing (...). The horse must (...) never lift in the front during the turns, but it has to lower the hindquarters and come under."

Stensbeck saw the danger of rearing up instead of actually sitting down. This danger still exists today, on the one hand if the canter is too collected, on the other hand especially if the circle is too centered. The uphill tendency is then given optically, but not through a relaxed and permeable settling on the hindquarters, but through a tense lifting out.

For the execution of the pirouette, Stensbeck further specifies: “The horse should not be tossed around as quickly as possible, but rather it should be placed under the back in the smallest possible circle ... .. canter around the hindquarters with the forehand. It is wrong to toss the horse into the pirouette, because then after the first half the horse will almost always change the canter lead behind... A real pirouette at a canter ends at the same pace as it began and begins at the same pace as you had before."

Stensbeck does not see the need for an additional collection for the so-called “pirouette canter” in order to be able to carry out a pirouette.

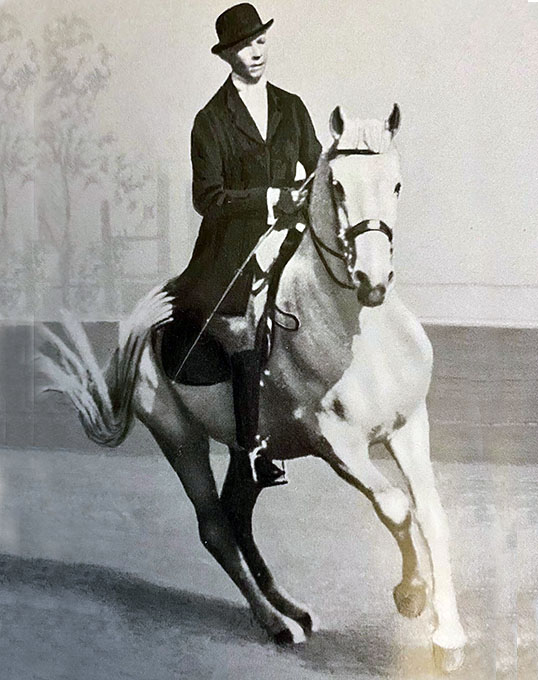

Podhajsky

Alois Podhajsky (1898-1973) explains in his book "The Classical Art of Riding - A Riding Lesson from Beginnings to Completion" (1980, Copyright 1965) how a pirouette can be worked out and points in particular to the problem of the not straight enough horse leaning at the introduction.

In the Spanish Riding School, the canter pirouette is tight from the renvers, according to Podhajsky, as it had also been taught by Guérinière. However, there is the danger, as with the beginning of the pirouette from the travers, that the horses get used to a certain crookedness before initiating the pirouette. That is why Podhajsky recommends putting the horse in a shoulder-in (pilié) fashion on the straight line, i.e. riding in shoulder-fore before the pirouette. And regarding the canter rhythm Podhajsky writes: "The canter rhythm before, during and after the pirouette must remain unchanged."

The usefulness of shoulder-fore like riding as preparation for the canter pirouette corresponds exactly to the new "Guidelines for Riding and Driving Volume II, Further Training for Rider and Horse" from 2020.

Seunig

Seunig then points out that in the Olympic dressage test, the pirouette is "laid out in a straight line on the track". "The slight longitudinal bend the horse has gained then corresponds only to the position required for the usual one in collected work - inner hind leg and inner front leg overlap, outer rear hoof about half a hoof width within the line of the outer front hoof", which corresponds to "riding in position".

Seunig also notes that a canter pirouette can only be carried out in school canter. He meticulously describes the four-beat of the school canter, which can be seen particularly well in "cinematographic recordings" and explains that due to the inadequacy of the human eye when looking at the foot sequence in the canter pirouette, deceptions can occur, so that one can sometimes believes to recognize a three-beat.

Seunig justifies the necessity of the four-beat in the canter pirouette: "because only in the pronounced four-beat is the horse able to canter through the pirouette in four to six strides in succession." This view corresponds to today's “modern” equestrian sport worldwide, but today six to 8 canter strides are allowed.

Up until the 1960s, the “school canter” was allowed in dressage tests, in which the inner hind leg and then the outer front leg of the diagonal that actually touched down at the same time were allowed in the canter pirouette.

Von Neindorff, Oliveira, Boldt

In this context, the question arises whether a pirouette can also be performed in clear three-beat. An answer can be found in Berthold Schirg, "The art of riding in the mirror of their masters, Volume 2, Olms-Verlag, 1992, p. 162. There he says: "But it is also possible to perform these exercises in a three-beat canter with the same swing and same beauty, what Mr. Neindorff and many others before him had proven. "

In a series of "studies" published by Sankt Georg Verlag in 1972, Egon von Neindorff (1923-2004) comments on the canter pirouette: "The pace in the pirouette should be exactly the same as in the collected canter on a straight line." However, he comments on the preparation for the pirouette: “It is best to shorten the last two strides almost to the canter on the spot and then turn away in a balanced manner.” And about the canter strides within the pirouette: “The canter strides also differ here from what is otherwise required in terms of gaining space: it must remain as small as possible in the rotation around the hindquarters with a clear three-beat."

In contrast to this, Nuno Oliveira (1925-1989) is quoted by Berthold Schirg in his work “The art of riding in the mirror of their masters” (Volume 2, Olms-Verlag, 1992, p. 162.): “The basic canter is a jump-like gait at three beat…. The premature touchdown of the front leg of the diagonal, which is simultaneous in the 3-beat canter, leads to a 4-beat canter on the shoulders. The premature touching down of a hind leg causes the 4-beat canter on the haunches ... This is the sequence of footfalls when cantering on the spot, when cantering backwards and when cantering in pirouettes ... Some also claim that the canter must always be in three beat, but you can canter on the spot and in pirouettes only in four beat."

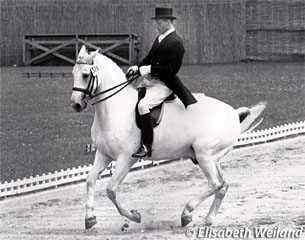

(Photo © Elisabeth Weiland)

Particularly noteworthy are Boldt's notes on the dosage of pirouette work: “Pirouettes should definitely not be overused too often, as they - if done correctly - mean a lot of effort for the horse and tend to put more stress on the joints, tendons and ligaments of the hindquarters. When used in a dosed manner, the pirouettes strengthen the hindquarters, and when practiced too often they lead to wear and tear. "

This fact has also led to the fact that in freestyle tests only a double pirouette is allowed to be shown.

Coming Soon: Part V - The evaluation of the canter pirouette from the point of view of the judges

Related Links

The Essential Guide to the Canter Pirouette - Part I: Origin Steeped in Military Training

The Essential Guide to the Canter Pirouette - Part II: Pirouettes in Cavalry Manuals 1826 - 1912

The Essential Guide to the Canter Pirouette - Part III: The "Cantering" Hind Legs Prevailed

Angelika Fromming: Half a Century of Dressage

The History of the Shoulder-In

The Essential Guide to the Piaffe - Part I: The Piaffe is a Means to an End